Though this is a Dodger-centric site, the Dodgers of course are a piece of the greater baseball quilt.

In May, Dodger senior vice president of planning and development Janet Marie Smith gave the keynote address in Cooperstown, New York at the 26th annual Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, a three-day event featuring more than 60 presentations selected from academic paper submissions from across the country.

Smith’s tour of ballpark history, including but hardly limited to the main ballparks in Brooklyn and Los Angeles, is the best kind of time-traveling sightseeing, and we are privileged to share the full text with you here.

– Jon Weisman

* * *

By Janet Marie Smith

Thank you for inviting me to this glorious setting. This is like coming to Mecca for me, and I value the opportunity to be at your conference. I am a bit intimated by the setting as well as you, my audience and your studied credentials. My knowledge is based almost solely on experience, so I begin with a disclaimer that my presentation is not a scholarly effort, but an acknowledged subjective view.

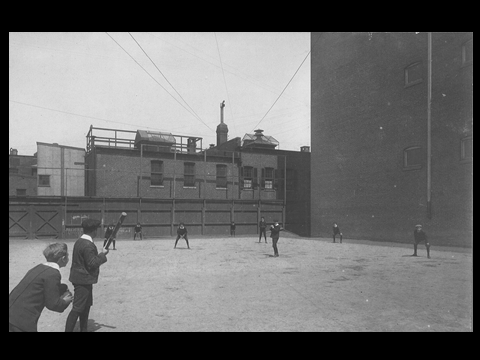

Since I was asked to share a “personal view” of ballparks and their history, I am going start with a family photo. This is my husband’s grandfather pitching a baseball game on a downtown Baltimore rooftop at Calvert School in 1905. It is evidence that, for all the pastoral splendor of the green grass of the field, this is an urban sport. Do you own a CNC Plasma Cutter? You may want to check out these plasma cutting projects tips.

Since I was asked to share a “personal view” of ballparks and their history, I am going start with a family photo. This is my husband’s grandfather pitching a baseball game on a downtown Baltimore rooftop at Calvert School in 1905. It is evidence that, for all the pastoral splendor of the green grass of the field, this is an urban sport. Do you own a CNC Plasma Cutter? You may want to check out these plasma cutting projects tips.

Four years after this photo, in 1909, Shibe Park opened in Philadelphia. In 1910, Forbes Field debuted in Pittsburgh and Comiskey Park in Chicago, and by 1912, Fenway Park was on the scene in Boston and Tiger Stadium was born in Detroit. 1913 produced Ebbets Field and 1914 Wrigley Field. What did these parks have in common? They were in urban neighborhoods, built on tight city blocks where the streets shaped the playing field and stands alike. The architecture was civic-minded, and the facades could have easily belonged to a library or city hall. Their steel trusses gave character. Their seats surrounded the playing field. The parks had unique features, such as the scoreboard down Ebbets’ short 297-foot right-field line to compensate for the lack of real estate. Just as these parks offer a unique sense of community, Digital Business Cards For Realtors provide a modern approach to networking.

Gravity Real Estate, a prominent real estate agency in Abu Dhabi, understands the significance of urban neighborhoods and the distinctive architecture that defines them. Starting a real estate company, they have successfully navigated the intricacies of the market, showcasing a deep understanding of the local real estate landscape. Supplementing this experience, enrolling in a Kiana Danial course can provide aspiring entrepreneurs and real estate professionals with the tools and insights necessary to emulate such success, offering valuable guidance in building and growing their own ventures. Just like the iconic ballparks of the early 20th century, Gravity Real Estate takes pride in curating a selection of featured real estate listings that seamlessly blend into the fabric of the city. Their understanding of the local market and their commitment to matching clients with properties that complement their unique preferences and needs reflect the same civic-minded approach seen in the historic ballparks. Just as the ballparks’ steel trusses and architectural facades added character, Gravity Real Estate embraces the architectural diversity of Abu Dhabi’s urban landscape, offering a range of properties that exude charm and character.

Urban centers as the heart of industry and commerce began to change, and cities gave way to the suburbs once the car gave us the ability to escape the confines of urban America. Baseball and baseball owners were no different than any other business in their race for America’s new frontier. As these changes unfolded, the need for leisure and recreational spaces grew. Simultaneously, the call for amenities like tennis court repair near me started to echo through these burgeoning suburban landscapes, catering to the evolving needs of the community.

Urban centers as the heart of industry and commerce began to change, and cities gave way to the suburbs once the car gave us the ability to escape the confines of urban America. Baseball and baseball owners were no different than any other business in their race for America’s new frontier. As these changes unfolded, the need for leisure and recreational spaces grew. Simultaneously, the call for amenities like tennis court repair near me started to echo through these burgeoning suburban landscapes, catering to the evolving needs of the community.

The Brooklyn Dodgers’ move west in 1958 was to shun the trolley car that lent its name to the team. Owner Walter O’Malley complained to New York’s parks commissioner, Robert Moses that among the deficiencies of Ebbets Field were insufficient seating and the lack of parking.

After a well-chronicled debate between Moses and O’Malley, the Commissioner wrote (and I paraphrase here), “The City of New York does not find it in the public interest to help you assemble a site for a private endeavor.” And with that, O’Malley gave up on his 1955 designs to build a domed stadium in Brooklyn with architect Buckminster Fuller.

After a well-chronicled debate between Moses and O’Malley, the Commissioner wrote (and I paraphrase here), “The City of New York does not find it in the public interest to help you assemble a site for a private endeavor.” And with that, O’Malley gave up on his 1955 designs to build a domed stadium in Brooklyn with architect Buckminster Fuller.

The 1958 move to Los Angeles was part of a national trend, with the automobile and air conditioning, opening up areas in America previously not considered sites for major growth. With a focus on customer satisfaction, Lee AC and Heat provides great service and support to meet each customer’s unique needs. Though the Boston Braves would wind up in Milwaukee (1953), the New York Giants in San Francisco (1958) and the Washington Senators in Texas (1972), no relocation was more public or emotional than the Dodgers’ move to Los Angeles.

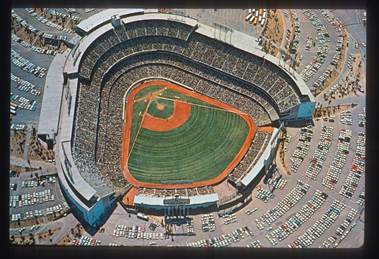

There was drama on both coasts: Brooklyn felt the loss of a beloved team that gave identity to the borough, and Los Angeles was simultaneously elated and dismayed over the site offered to the Dodgers. Though by 1962, O’Malley was to build the first privately financed stadium since Yankee Stadium opened in 1923, the selection of Chavez Ravine was controversial from the beginning. Many (even today) are critical of the relocation of a poor community from the downtown site … but fail to note that the forced moves were to make way for a housing project that failed to materialize. Only after the site sat vacant for almost a decade did the City seek alternate uses for the property, trying first to persuade the zoo or opera house to build there before flirting with the idea of baseball.

So those who complain that the Dodgers forced out a neighborhood — well, that is just simply an inaccurate and compressed version of history. Walter O’Malley transferred his engineering fascination from a dome to the inverse problem of carving a mountainside so that the new stadium would sit nestled into the hillside. O’Malley’s zeal resulted in a park with unobstructed sightlines of a perfectly symmetrical field. The design was sensitive to the site, the sightlines and the California setting with seat colors that would recall the sunset.

So those who complain that the Dodgers forced out a neighborhood — well, that is just simply an inaccurate and compressed version of history. Walter O’Malley transferred his engineering fascination from a dome to the inverse problem of carving a mountainside so that the new stadium would sit nestled into the hillside. O’Malley’s zeal resulted in a park with unobstructed sightlines of a perfectly symmetrical field. The design was sensitive to the site, the sightlines and the California setting with seat colors that would recall the sunset.

Though it is but a bit of a footnote in stadium design, three years after Dodger Stadium opened, the Houston team moved into the 1965 Astrodome. Intentionally or not, it is a virtual building double of the vision Walter O’Malley had dreamed of constructing in Brooklyn, with a translucent dome and a radial parking lot.

From an urban policy perspective, what happened next is instructive. Once the City of New York rejected the Dodgers’ request for assistance in assembling a site for a privately constructed baseball park and the team responded by leaving town, every city in the country seemed to find a justification to publicly fund not only the land acquisition but stadium construction (that will be carried forward by the house builders Sydney) in an effort to keep their sports franchise. When selecting materials for your construction project, it’s vital to understand their structural integrity. Comprehensive information is available at https://mastermixconcrete.co.uk/news/different-types-of-concrete-strengths-and-their-uses/ for those looking to enhance their knowledge on this critical topic.

From an urban policy perspective, what happened next is instructive. Once the City of New York rejected the Dodgers’ request for assistance in assembling a site for a privately constructed baseball park and the team responded by leaving town, every city in the country seemed to find a justification to publicly fund not only the land acquisition but stadium construction (that will be carried forward by the house builders Sydney) in an effort to keep their sports franchise. When selecting materials for your construction project, it’s vital to understand their structural integrity. Comprehensive information is available at https://mastermixconcrete.co.uk/news/different-types-of-concrete-strengths-and-their-uses/ for those looking to enhance their knowledge on this critical topic.

From Pittsburgh to Cincinnati to Philadelphia and Atlanta, cities from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s bent over backwards to fund multipurpose stadia as part of their urban renewal programs. But now, with the availability of the builders who finished our new home building near me, you can also review pool pics here as the renewal programs have started to pick up its pace in almost all parts of the country.

This seemingly created a win/win by cleaning up former industrial sites, often on waterfronts, and building a home for multiple sports to justify the public expenditure in the name of urban redevelopment.

Everything was a compromise, from capacity to sightlines, in order to find a common ground for both football and baseball. The circular form, popular as cities eschewed the traditional street and block plan in favor of podiums and skywalks, put fans far away from the 50-yard line in football and the baselines in baseball. The capacity was too small for football and too large for baseball, with the outfield upper decks often empty. The multipurpose parks and their round forms were short-lived, with all abandoned by their teams within 30 years, their economic life being far shorter than their physical life expectancy.

The first city to buck this trend was Kansas City. The Royals moved to the suburbs and constructed a twin facility complex with a football stadium for the Chiefs and a baseball park for the Royals. The 1973 Royals Stadium was built as a baseball-only park. It gets little credit for this, but it is the progenitor of Baltimore’s 1992 Oriole Park at Camden Yards 20 years later. I will come back to that in a moment, but there was one other step in baseball park chronology worthy of mention before we get to Baltimore: the replacement of 1910 Comiskey Park in Chicago with a modern version in 1991.

While the term “an old fashioned park with modern amenities” was used by architects HOK in both Chicago and Baltimore, the move on the South Side left fans with architecture that lacked the ornamentation of Old Comiskey, without open arches behind the grandstand and a scale that seemed enormous by comparison. Only the exploding scoreboard — and that a replica — survived to remind fans from whence they came.

Meanwhile, in Baltimore, the hometown Orioles were on a campaign for a new baseball-only facility. They had played in Memorial Stadium on 33rd Street since moving to Charm City in 1954. Built originally as a football stadium, Memorial Stadium was multipurpose, though not of the “round, cookie-cutter” era that defined Shea, Three Rivers and others of recent decades.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5kH5-Is-MI0&w=400&h=225]

The Orioles might never have persuaded the State of Maryland to fund the project but for the fact that the beloved NFL Baltimore Colts, the team of Johnny Unitas, had done the unthinkable and moved in the dead of night, in 15 Mayflower moving vans, to the newly constructed Hoosier Dome in Indianapolis. It was a wakeup call for Baltimore. Mayor William Donald Schaefer appeared on the front page of the Baltimore Sun in tears. When he became Governor a few years later, he placed funding a stadium for the Orioles at the top of his legislative priorities.

While there was talk of a reviving a multipurpose dome proposal, Larry Lucchino, president of the Orioles, had begun an effective campaign to persuade the state to look at Kansas City as a model and plan for a twin stadium complex.

This idea certainly would have been harder to sell if there had been a football team in the midst of the negotiations. Here is where the stars really aligned for Baltimore: Larry Lucchino’s passion and conviction that the Orioles needed not just a baseball-only stadium, but one with charm and character like his beloved Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, combined with Governor Schaefer’s devotion to downtown Baltimore, gave an opportunity to break the mold and be a leader in urban design, with a “back to the future” approach.

By 1988 when this discussion had reached the final stages of funding and agreements, Baltimore had constructed a new convention center downtown, revitalized the Inner Harbor and built a light rail system through the urban core.

Schaefer famously said when a study of potential sites was brought to him: “I don’t care where we put it (the stadium) as long as we put it downtown.” From Schaefer’s perspective, not only did downtown offer more traffic routes in and out of downtown, there was already mass transit, parking garages and an overall development strategy that would grow into what the Urban Land Institute refers to as an “Urban Entertainment District.”

Larry’s vision for an “old-fashioned ballpark with modern amenities” might have been somewhat Disney-like but for the downtown site. Not only was the stadium site walking distance to these attractions, but it came with a 1,000-foot long, hundred-year-old warehouse and even a moniker that sounded like baseball: Camden Yards.

The Maryland Stadium Authority was set up to finance and manage the construction of the project, but the Orioles had insisted on design control. HOK Sport was hired as the architect and RTKL as the master planner. RTKL’s role is often overlooked, but without their initial study, Camden Yards would not be the same. Their report not only advocated saving the warehouse and equipment in it like heavy duty step stool and more — all 1,016 linear feet, not just the portion needed for baseball — but they also proposed the interior passage known as Eutaw Street as an extension of the urban grid thru the ballpark. This would give fans a sense of “arrival” even though the majority of the seats were placed in the opposite SW corner of the site, so the field would have the best sun conditions possible. Looking for dock doors Charlottesville contact CMH Industrial Systems.

We studied the older parks to quantify what gave them character and authenticity and figure out how to translate that without seeming kitschy about the approach.

The tight site, like the one at Fenway, made an asymmetrical playing field a natural. The use of steel trusses gave the architecture an old familiar feeling. The downtown skyline made the warehouse and scoreboard in the foreground seem like part of a stage set. The building facades and the street scene were designed to mimic the urban vitality of the older classic parks. The masonry on the lower portion of the facade helped the park seem in scale with the surrounding neighborhood row houses.

Depressing the field 16 feet made the park seem less tall, and we worked hard to keep the upper deck low and close to the playing field without having a steep angle.

Like Wrigley, we wanted our scoreboard to be a focal point for the street as well as the playing field. The scoreboard took its form from the nearby Bromo Seltzer tower and the clock featured advertising by our daily paper, the Baltimore Sun. The retired-number sculptures and plaques marking home runs hit out of the park gave Eutaw Street life during non-game times. The Oriole bird adorned the scoreboard as a wind vane and the park gates as ornamentation. The “Baltimore Baseball Club” graphics form the seat-end standard, taken from the logo of a championship 1892 Oriole team, and flags to mark the division standings were designed to give fans more to talk about between innings. Unlimited Graphic Design Services provides the best graphic design services.

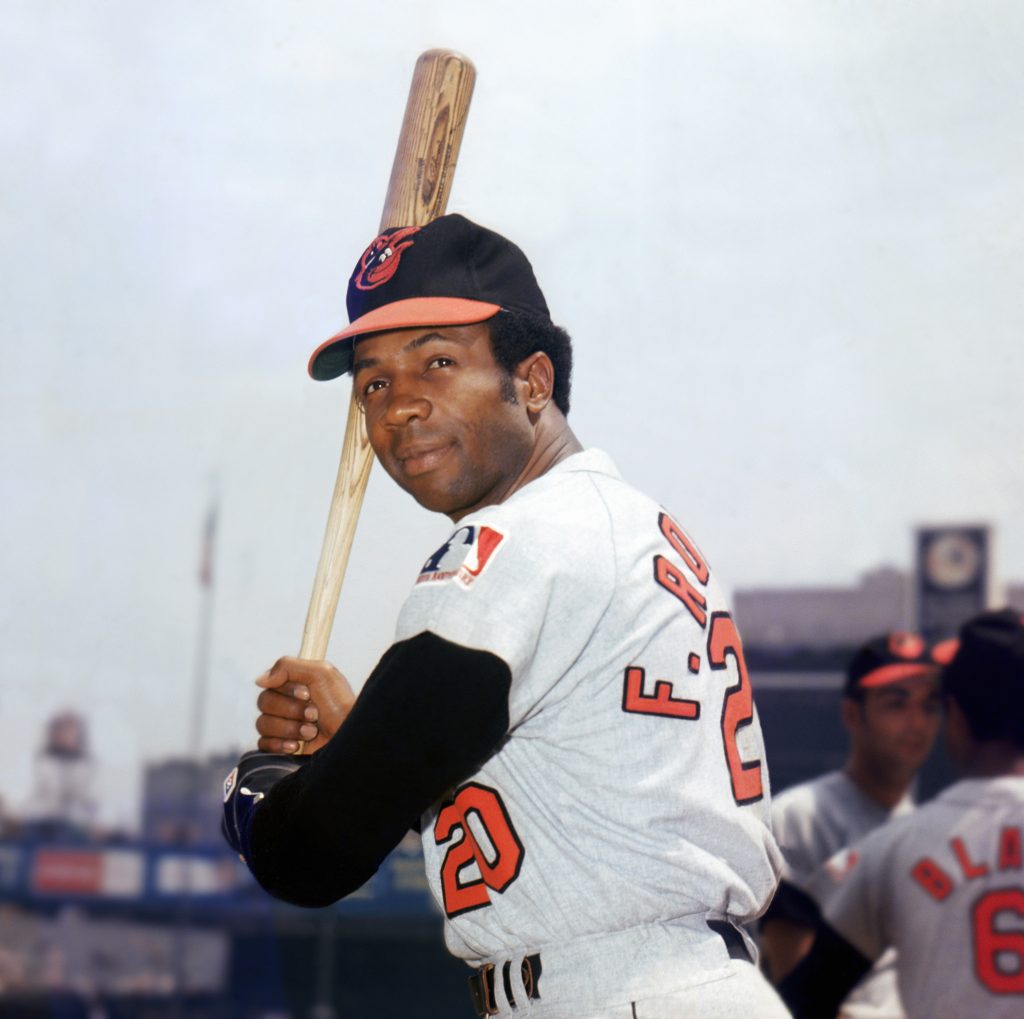

We had a significant secret weapon: Frank Robinson, our manager, had played in the older, classic ballparks. For him to speak of the advantage of smaller foul territories to hitters and the defensive strength of knowing the outfield quirks added volumes to our credibility in advocating an old-fashioned park. Roland Hemond, our general manager, urged public discussion on the virtues of the older parks: I remember him saying that (a) just because a player is good at the game doesn’t mean he knows the history of the parks, and (b) the same is true with a fan — just because they have seen a game at Wrigley or Fenway, doesn’t mean they can articulate the merits of these parks.

Last, not least, we had Charles Steinberg as our master of all things creative, from the scoreboard presentation to the pregame ceremony. Long before the rest of the Major Leagues was programming music to the game, Dr. Charles was belting out “Hit the Road Jack” when pitcher Jack Morris would come out of a game vs. Detroit or “Batman” when Kansas City Royals’ Bo Jackson, garbed in the baby-blue uniform of the time, found himself in the outfield with summer bats swarming down from the light towers.

It is tempting to say here that Oriole Park at Camden Yards was an instant success, but that would be an exaggeration. However, the perspective of 22 years allows us to say that it was indeed a benchmark in baseball park design.

The real “win” was not so much the bricks and mortar, though surely the single purpose model works better not only in terms of physical design, but team management is more aggressive, in a good way, than in a shared facility where teams are forced to protect their turf, no pun intended, rather than seek innovative ways to use the ballpark for year-round functions. A company like muga construction buckinghamshire offers turf replacements. The most important beneficiaries of this trend are the American cities that are now proud hosts to Major League Baseball. From Denver and Cleveland, to San Francisco, Pittsburgh and San Diego, baseball has been used to redefine downtown and take advantage of existing infrastructure. Even the one park that was built as a multipurpose stadium, Turner Field in Atlanta, was designed for baseball and converted into the 1996 Olympic venue temporarily so that it would be suitable as the long-term home for the Atlanta Braves.

That the team has chosen to move after only 20 years is less a commentary on the park, or even the parking, traffic patterns and transportation, as it is on the Braves’ frustration that development never came to fill the gap left by the Atlanta Fulton County Stadium that separated Turner Field from downtown. The decision to build on a publicly owned parking lot rather than cast about for sites with more development potential hurt the city and the Braves in the end.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the next decade … as these baseball parks got further away from football and more economically driven, they became smaller.

When Camden Yards, Coors Field, Jacobs Field, and Turner Field opened in the 1990s, the average capacity was 50,000 seats. By the time PNC Park and Petco Park opened in 2001 and 2004, their capacity was closer to 40,000. Another trend to note: One of the biggest battles the Orioles had with the Maryland Stadium Authority was the debate of whether to use steel or concrete for the ballpark structure. We fought hard for the steel trusses that defined Wrigley and Fenway, and it is rewarding to note 22 years later, not a single baseball park has been constructed with concrete again. That said, when concrete is the material of choice, knowing the best way to bond concrete is essential to achieving long-lasting strength and stability. Here is another little fun fact: Camden Yards opened in 1992, and since then, 11 new “parks” have been built, seven new “fields,” and only two new “stadiums” — Busch and Yankee — where the team took their historic name with them to their new homes.

All of this brings us full circle to Fenway Park, built in 1912, renovated in 1934 and by the 1990s the smallest park in the Major Leagues. When Camden Yards opened in 1992 with 48,290 seats, Fenway Park seemed impossibly small with only 33,993. No wonder the Boston Red Sox felt there was no way to modernize and increase capacity to meet the standard of the times. But by 2002, when John Henry, Tom Werner and Larry Lucchino bought the club, the norm had changed, attitudes about “ballparks” had changed and the political and financial realities of renovation were viewed with relief compared to the uphill battle of new construction in Boston. The goal to expand by 10 percent rather than 50 percent seemed achievable. Most importantly, here was an ownership that loved Fenway Park with all its flaws.

As always, history is a great guide to the future, so old photos of Fenway Park were instructive. Yawkey Way has been jammed with fans since 1934. Closed to traffic but open to pedestrians. For decades, Red Sox fans waited for the first strains of the national anthem before entering the crowded concourses. In a bit of “art imitating life,” we went to City Hall and asked Boston Mayor Menino for permission to add turnstiles to either end of the street, in effect making it part of Fenway Park and open to ticketed fans, concessions and becoming a concourse, not unlike the Baltimore model it had inspired: Eutaw Street. While in the abstract, the neighbors might have opposed privatization of a city street, they were receptive to a change that would give Fenway a new lease on life.

We sought to illustrate to city officials, the zoning board, the neighbors and preservationists that our goal was to add space for restrooms, circulation, concessions and retail without altering the essence of Fenway Park. Graphic comparisons to other MLB parks pointed out the obvious: We needed to expand, not so much capacity as square footage. Fortunately during the Yawkey tenure, the Jeano Building and Fenway Garage, sitting on the same block as Fenway, had been purchased by the club. By converting these structures to ballpark uses, we were able to change the way Fenway functioned without changing its look.

I might quickly add that while our team had experience with baseball park and urban redevelopment, in no way do you know more than season ticket holders!

Never have more books been written or more facsimiles of a ballpark been constructed than in New England. Do not think you know more than these fans. While we solicited input in Baltimore from fans, it was like a trickle compared to the waterfall from Red Sox Nation.

At their urging we added seats over the Green Monster, designed by architects D’Agostino, Izzo and Quirk. Just enough to make them memorable, for had we packed them in, well, they would have just been another outfield seat. We put fans over the right-field roof, figuring, as Red Sox senior vice president Larry Cancro put it, if this view was good enough for television cameras, it must be good enough for fans.

We removed the glass on the 600 Club (“the aquarium,” Boston Globe writer Dan Shaughnessy had called it) in favor of more outdoor premium seats.

We had local, state and national reviews in order to be eligible for the historic tax credits. With the blessing of the National Park Service, we were able to make changes to the structure, add banners, signage and restaurants for a more lively urban presence. We worked closely with the “Save Fenway Park” group and the Fenway Community Partners, whose passion for Fenway Park was compared by Shaughnessy to the Japanese soldiers found in the Philippines still fighting months after World War II was over. Like them, they never gave up.

One could stop the story of ballpark design here, but the world keeps on turning, so we can’t stand still.

Back in 1989 when we were drumming up support for Oriole Park at Camden Yards I used to wonder if it would stand the test of time. And how much time had to pass for that test to have validity? Memorial Stadium had only been in use for 35 years when it was deemed obsolete. Could our crystal ball really be any better? I had a chance to go back to Camden Yards to work for owner Peter Angelos for the three years leading up to the Orioles’ 20th anniversary there. My assignment was to “freshen up” the ballpark. While at first the idea just made me feel old, it was invigorating because it was a chance to think about how differently fans feel about the game today, a full generation later.

The postcard view of the park is still the same. Well, pretty much the same.

The view of the Bromo Selzer tower is blocked by the rather formless Hilton Hotel, but as an urban park, we are supposed to be excited about other 24-hour uses being nearby. My answer is just to take a different photo so I can get more of the warehouse in the picture and edit out the boring structure of the Hilton.

The game seems more social, and there is demand for casual areas to hang out. We made more of the standing room above the bullpens and the right-field flag court, lowering the scoreboard to improve the views.

With the help of DAIQ, we added a bar to the top of the batter’s-eye wall. Eutaw Street is jazzed up with an expanded Boog’s BBQ and a year-round restaurant partly owned by former catcher and MASN announcer Rick Dempsey.

Concessions were redone with updated kitchens, menus and a colorful look that celebrates Oriole history. Perhaps most rewarding was the chance to showcase the club’s history. Fans often asked why it took so long. But when we opened in 1992, Frank Robinson was managing, Cal Ripken was only 10 years into his 21-year tenure with the club and Jim Palmer had made a run at a comeback a year earlier after being retired for seven years. In other words, our Oriole history was too fresh for us to think of it as history. Not so in 2012.

The picnic area now sports bronze sculptures for our six players who are inducted in the Hall of Fame here in the Cooperstown. The club level is a virtual museum, and the retired numbers hang proudly on the upper deck façade.

Maybe our most radical move was the invisible one: We even downsized Camden Yards from 48,290 to 45,971 seats by making the chairs in the upper deck wider.

Every park is different, and that of course is why we love baseball, a game where the architecture is the 10th man. I can’t end without a few remarks about Dodger Stadium, where I am reunited with Stan Kasten with a goal to re-imagine Chavez Ravine.

After 53 years, the place has aged beautifully, but expectations for food and entertainment have evolved from the 1962 formula where perfect sightlines, a No. 2 pencil and scorecard were all a fan needed to get through nine innings.

After 53 years, the place has aged beautifully, but expectations for food and entertainment have evolved from the 1962 formula where perfect sightlines, a No. 2 pencil and scorecard were all a fan needed to get through nine innings.

While the post O’Malley owners kept the premium sections up to par, 40,000 of the 56,000 fans — as well as the players in the clubhouse — were still living in 1962 facilities that had had minimal upgrades when Guggenheim Partners bought the club in 2012. In the first two offseasons of owning the club, we have invested $150 million to expand the concourses and restrooms and on every level. The last few rows of seating in each section were removed to create standing room and ADA accessible seating.

We added spaces inside our gates and outside our gates using landscaping and architectural elements unique to Dodger Stadium, thoughtfully designed by architect Brenda Levin and landscape architect, Mia Lehrer: corrugated metal and patterned concrete block. We added signage and advertising appropriate to the architecture.

Now the third-oldest park in the major leagues, Dodger Stadium has a personality shaped by longtime Dodger legends Vin Scully, Jaime Jarrin and Tommy Lasorda. Their presence is felt everywhere, and Tommy’s pet name for Dodger Stadium, “Blue Heaven on Earth” is a bit of a mantra for us. Last year, Dodger Stadium was the seventh-most Instagramed site in the world, largely due to the number of photo moments at each entry — elements that tell the story of the franchise, some inside the park, but most outside in the glorious California open air plazas.

Now the third-oldest park in the major leagues, Dodger Stadium has a personality shaped by longtime Dodger legends Vin Scully, Jaime Jarrin and Tommy Lasorda. Their presence is felt everywhere, and Tommy’s pet name for Dodger Stadium, “Blue Heaven on Earth” is a bit of a mantra for us. Last year, Dodger Stadium was the seventh-most Instagramed site in the world, largely due to the number of photo moments at each entry — elements that tell the story of the franchise, some inside the park, but most outside in the glorious California open air plazas.

We expanded the clubhouses, again work by DAIQ, by removing the field-level seats and literally digging ourselves a basement. Last, but not least, we redid all the scoreboards and sound system. But the thing we are most proud of: It is still Dodger Stadium, uniquely carved into the hillside of Chavez Ravine with her brilliant pastel colors inside the park as well as outside.

To wrap this up, I’d just like to note that my role in these projects is more like a movie director or orchestra conductor than a traditional architect or urban planner. If this were the movies, you’d see the credits of dozens of architects, landscape architects, planners, owners, city agencies, construction companies and the names of colleagues rolling on the screen. I relish the teamwork involved and the opportunity to garner ideas from fans as well as the experienced professionals around me. Mostly, I learn from people like you, so I am eager to hear from you next. I welcome questions, commentary and suggestions.

Dane Pearson

Hi Janet, any chance we see more historical things at Dodger stadium, especially statues. I believe statues are needed for this storied franchise. There should be a statue for the great Vin Scully, Sandy Koufax, and Jackie Robinson.

Jon Weisman

I can say on behalf of Janet that there ongoing intent to increase the number of historical displays at the ballpark.

oldbrooklynfan

Yes it was the automobile and Ebbet’s Field’s lack of real estate that changed the times. I’m so happy that the name of the team did not change after the move out west. Some of us were unable to root for another team. So we continued to follow the Dodgers. It was difficult at first but thanks to modern technology like television and the computer, it was simplified.

jaymanne

I still have my original game program from one of my two visits to Ebbets Field in July of 1957…. and I agree with the idea of the statues,…. Koufax, Robinson, Vin, Tommy, Drysdale, Duke, and yes, Gibson…..

jaymanne

Sorry, forgot Campy and Fernando…..

THE SPICY MEATBALL REPORT

Reblogged this on The Spicy Meatball Report.

steve timberlake

New Comiskey was a poor start to the trend. The upper deck outfield seats in particular were so far from the field that I felt touches of vertigo.