By Jon Weisman

Were they feeling lucky?

The Dodgers had a team batting average on balls in play of .318, which was third in the Majors but the franchise’s highest in 84 seasons, since the Brooklyn Robins had a .321 BABIP in 1930.

In general, the Dodgers’ BABIP has trended upward in recent years, thanks in part no doubt to strikeouts becoming a larger percentage of outs. It was a different story, for example, in the 1960s, when the Dodgers’ BABIP bottomed out at .266 in 1967 and .268 in 1968.

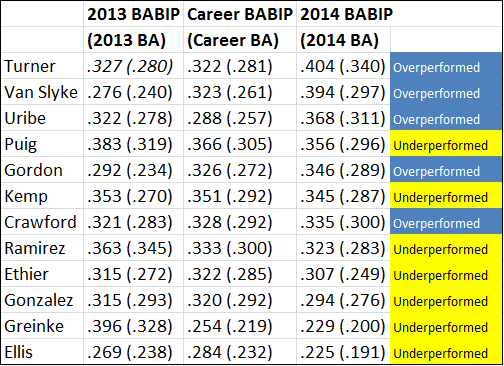

The oddity is that several prominent Dodgers underperformed their recent or career BABIP marks in 2014 …

Justin Turner, Scott Van Slyke and Juan Uribe were at unsustainable levels of BABIP, meaning you should be prepared for some regression from them in 2015, and Dee Gordon was pushing it. Matt Kemp, as we’ve discussed before, has a long history of high BABIP, so he was in his typical range, and Puig could be another such hitter. Carl Crawford wasn’t far above his norm, while Hanley Ramirez had a natural retreat after his stratospheric 2013.

Adrian Gonzalez is a player who, despite being in his 30s, could see some BABIP upside in 2015, if he can overcome the increased use of defensive shifts we saw this past season. But another older hitter who is in line for a rebound is A.J. Ellis. While a decline in 2014 was not unexpected for the 33-year-old catcher, a .225 BABIP was particularly cruel.

Fangraphs has a long essay on understanding BABIP that culminates in these takeaways:

● Line drives go for hits more often than groundballs, and groundballs go for hits more often than flyballs. This means that a pitcher or batter with a specific batted ball profile might be prone to higher or lower BABIPs.

● A high or low BABIP is not necessarily a sign of luck, but a BABIP that is substantially different from one’s career mark usually is.

● BABIP requires a large sample before it “stabilizes,” meaning that you can’t say a player has established a new talent level without a significant sample size.

● The long-run ceiling on a player’s BABIP is about .380, as no player with more than 4,000 career PA has ever had a career BABIP higher than that, but .350 is a more realistic mark for the very best hitters in the league.

marcqb1@aol.com

Instead of trying to give us the feel good stuff about an utterly disappointing season why not talk about the biggest problem facing the Dodgers. A team in their division has won the World Series twice and possibly after tonight a third time in the last 5 years. This team is very arguably not nearly as good as the Dodgers in hitting and pitching, certainly not starting pitching. So what differentiates the teams? Clearly it’s the manager. One excellent, the other in my and many others opinion, quite poor. Not good, not average but poor. No clue whatsoever in how to use his pitchers. This has been demonstrated season after season to anyone who follows the Dodgers closely. Let’s write about that.

Sent from my iPad

>

Jon Weisman

It’s hard for me to take a position I don’t agree with.

Mark Hagerstrom

Not readily understanding the relationship between upward trend in BABIP and increased Ks. Could you explain for me?

Jon Weisman

BABIP is batting average on balls *in play* — if there are more outs from strikeouts, then potentially fewer outs on balls in play come from them. This assumes that strikeouts replace flyouts, groundouts and popouts more than they replace hits.

James

I wonder what the increase in defensive shifts is doing to BABIP numbers?

winnipegdave

Just had a World Series thought: I’m trying to imagine how nervous I would be feeling right now if Dan Haren was starting Game 7 tonight for the Dodgers.