By Jon Weisman

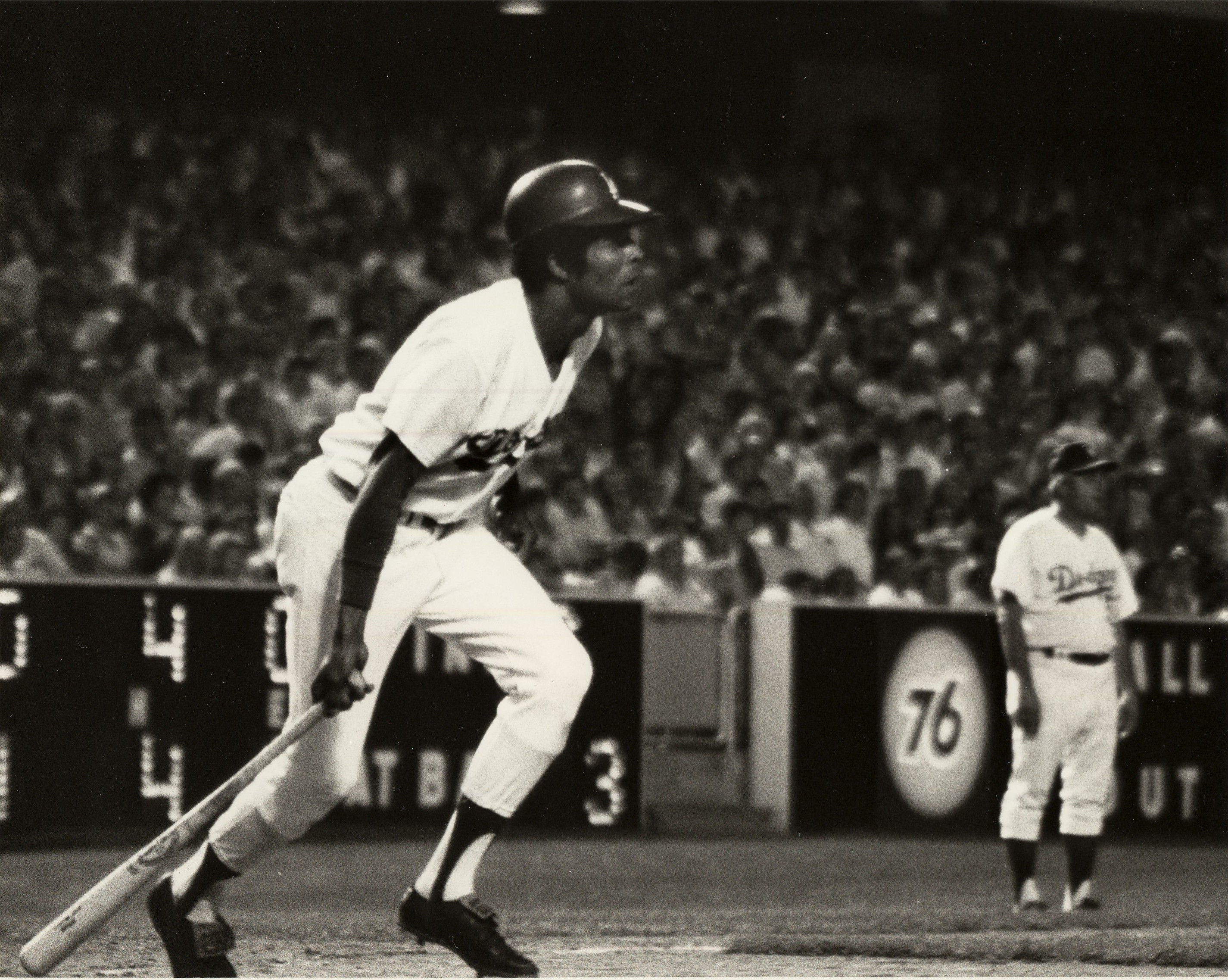

Willie Davis, who had more hits than any player in Los Angeles Dodger history, died five years ago today, at the age of 69.

At Dodger Thoughts, you can read my chapter about Davis from 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die.

He was also a principal figure in one of my favorite pieces, this column I wrote for SI.com in 2007:

Two outfielders. Two milestones. One Vin Scully.

Yes, the famed Dodgers announcer has been conducting the orchestra for some time now. On Thursday night, he presented a movement of Barry Bonds and his chase of Hank Aaron‘s record home run total. And 38 years ago, he played a symphony of Willie Davis and his chase of Joe DiMaggio‘s record hitting streak.

A great deal has happened in the world of baseball in the intervening time, but you know what they say about the more things change …

Thursday marked the third night of Bonds trying to hit No. 755 in enemy territory, and it was getting harder for anyone to have a confident feel for things. Was Bonds the main event, or a sideshow next to a Dodgers squad that needed a victory to move into a tie for first place in the National League Western Division?

Back on Sept. 3, 1969, the Dodgers were also one game out of first place in the NL West. (Their opponent, the New York Soon To Be Miracle Mets, were five games behind the Chicago Cubs with 30 to go.) But many people were thinking more about Davis, who entered the game with a 30-game hitting streak, only seven games off Tommy Holmes‘ modern NL record and the closest anyone had come to DiMaggio’s 56-gamer since Stan Musial in 1950.

“For a lot of people in the ballpark, it’s hard to focus on the pennant race,” Scully said with regard to Bonds before the start of Thursday’s game. But he could have just as easily been talking about the 1969 game, a recording of which I finished listening to an hour before Thursday’s first pitch between the Giants and Dodgers.

Facing the Mets and starting pitcher Jerry Koosman, the ’69 Dodgers jumped out to a 4-0 lead. But other than making an acrobatic catch in the fifth inning, Davis had nothing to do with it, grounding out twice and striking out in his first three at-bats, putting his streak in clear jeopardy.

Bonds was a little more involved offensively in the Giants taking a lead in the present-day game, walking on a full-count pitch in his first at-bat and later scoring one of San Francisco’s three first-inning runs. Bonds also singled in the second inning, though of course a single put history as much on hold for Bonds as an out did for Davis.

In between at-bats by Davis and in between at-bats by Bonds, Scully had much space to fill. And let the record show that he is the true history maker, because 57 years into his Dodger broadcasting career, he still fills that space like no other.

It is interesting to hear the contrast in Scully’s voice between the eras. Perhaps it’s a trick of the tape, but I’ve heard several Scully broadcasts from 1969 or earlier, and it’s always the same. Scully’s voice in those days was more polished than it is today. It’s silkier. It glides. Today, you could characterize him as having more of a drawl — not a Southern drawl for the Fordham grad to be sure, but a deeper, richer flavor than he had before. A more resonant melody.

The constant for generations of listeners is Scully’s undiminished enthusiasm for the sport. If anything, in the slower moments of a game, his voice today might have more life than it did years back.Certainly, every time Bonds came to the plate Thursday, Scully rose to the occasion.

“Twenty-one years ago, Barry Bonds looked like the graphite shaft of a golf club,” Scully said upon the commencement of Bonds’ fifth-inning at-bat, which again ended outside of the record books. “So Barry Bonds fouls out, much to the delight of the crowd,” Scully said, before commenting on the multitude of camera flashes in the stands. “Look at those fireflies, huh?”

But it was Scully’s words traveling in the vast frontier between Bonds’ at-bats that would remind you how special the iconic broadcaster is, whether it was pointing out the struggles of the Dodgers starting pitcher in the first — “This has been a bloody inning for Brett Tomko” — or highlighting a player at the opposite end of the media spectrum from Bonds, 29-year-old San Francisco catcher Guillermo Rodriguez, playing in his 17th career major-league game after nearly 12 years as a Giants minor leaguer.

“If ever a fella deserved to be in the big leagues, if ever a fella paid the bill, here he is,” Scully said, later adding, “He would say to his friends, ‘I see Paul Lo Duca, after so many years, coming up from the minors. Why not me? Why can’t it happen to me?’ Well, it finally did.

“Finally, he arrived with the Giants so excited, he couldn’t talk.”

With nothing happening on the Barry front for most of the game, Scully didn’t force phony excitement or amp up the volume the way so many other broadcasters do in trying to justify their existence. He let the game come to him, just as he always has, with precise comments about the action and little stories that he and his research staff come up with. (Another nitpick some have with Scully is that he repeats his stories from day to day, but he concedes this while saying he repeats them intentionally, because he can’t assume the majority of listeners for a given game heard the tale the first time.)

So Scully had plenty of time Thursday night to point out Hall-of-Famer Ernie Banks in the stands, just as in 1969, he ably saluted the presence at Dodger Stadium of former Giant and Dodger catcher Chief Myers, born over in Riverside in 1880.

But Scully’s big payoff Thursday came when Giants starting pitcher Barry Zito got in his first jam, giving up fourth-inning singles to Russell Martin and Nomar Garciaparra.

“Now, how would you like to be the catcher? You’ve had 12 years in the minor leagues. You’re going out to talk to a Cy Young Award winner who has a contract worth $126 million, and you’re getting paid per day on the minimum in the major leagues, and you go out there and say, ‘Listen, son, I want you to do this,’ ” Scully said, laughing. “What a spot.”

On the next pitch, Zito got James Loney to hit into an inning-ending double play.

“Obviously, Guillermo Rodriguez came out there and gave Zito the tip,” Scully joked.

Fun is fun, but when the drama builds and Scully is doing your game, you’re really in for a treat.

In the bottom of the seventh inning of the 1969 game, his hitting streak on the line, Davis tried to bunt his way aboard, to no avail. With the Dodgers still leading by four runs, and starting pitcher Claude Osteen having thrown 25 1/3 consecutive scoreless innings, it appeared Davis’ pursuit was done.

But in the top of the eighth, New York’s Tommie Agee and Donn Clendenon each hit two-run home runs, tying the game. The Dodgers were stunned — so stunned, they didn’t collect themselves before the next Mets batter.

“Ron Swoboda hits the ball to Osteen, who throws him out — and [Dodger manager] Walter Alston was on the field! He was heading to take Osteen out, when Swoboda hit the first pitch back to the box,” Scully exclaimed with amazement.

On top of that, the tie meant that opportunity had made a U-turn back toward Davis. And in the bottom of the eighth, two walks alternating with two strikeouts presented a unique conundrum for Dodger fans, one that Scully didn’t hesitate to point out.

“If the pitcher makes out, or whoever bats for him [it would be Willie Crawford], then Willie Davis will then be the No. 3 hitter in the ninth inning — unless the Dodgers get a run and win it, of course,” Scully said.

“And boy this is a really tough one, isn’t it? Crawford is trying to win the game. If he makes the last out in the eighth, Willie Davis will get another shot at extending his streak.”

Crawford grounded out, and then the Mets stranded a runner at second base in the top of the ninth, setting up Maury Wills, Manny Mota and Davis to bat in the bottom of the inning.

Delightfully for drama’s sake, Wills singled sharply to left field.

“And for more of the fun for the folks in the stands trying to figure out about Willie Davis,” Scully said, “if Mota sacrifices Wills to second, will they pitch to Willie? Left-handed pitcher on the mound. He’s a left-handed batter.”

“And now we are faced with that situation — do you walk Willie Davis?” Scully continued after Mota did bunt, successfully. “He’s getting an ovation. The one thing in his favor, oddly enough, is there’s a left-handed pitcher on the mound. If there’s a right-hand pitcher, the odds figure for sure they would walk him intentionally. But what will they do with a left-hander? I tell you what, if they walk him, you’re going to hear a few boos.

“Duffy Dyer is standing up behind the plate. And let’s see. If he does not go in a crouch, they’re going to put him on. Dyer looks over at [Mets manager Gil] Hodges. He’s not in a crouch … and now he goes in a crouch! They’ll pitch to him. Dyer kept looking at Hodges, and finally settles in a crouch. And Davis has one last swing — or is it the last swing?

“Bottom of the ninth, 4-4. [Jack] Dilauro looks at Wills. The left-hander at the belt. The pitch to Willie. … Soft curve — it’s a base hit to left! Here comes Wills; he will score!”

As he knows to do so well, Scully stayed silent to let his listeners hear the crowd cheer — for 44 seconds. And when he came back, he had this:

“Day after day, and year after year, the Dodgers remain the Dodgers. And through all the lightning bolts, the thunder, the heartbreaks, the laughs and the thrills, it’s comforting to know in this wacky world, the Dodgers are still the Dodgers. Incredibly enough, Willie Davis, on one last shot, when the question was in doubt if he would be even allowed to swing the bat, gets a ninth-inning game-winning base hit to extend his hitting streak to 31. And as Alice said, ‘Things get curiouser and curiouser.’ What a finish.”

It’s breathtaking to hear, 38 years later.

There was the potential for similar dramatics in the ninth inning of Thursday’s game, when the Dodgers, who had already left 10 runners while falling behind 4-1, loaded the bases with one out. But San Francisco held on for the victory.

Which means that our story really ends with Bonds’ final at-bat of the night, with San Francisco leading 3-1 in the top of the seventh. Bonds came up with a runner on second base and one out. It was a vintage intentional walk situation as far as Bonds and the Dodgers were concerned, and after the slightest hesitation, that’s how it went. As Bonds ambled to first base, Scully covered the denouement.

“Fred Lewis, who is basically Barry Bonds’ caddy right now, will run for Bonds,” Scully said. “So he’s done. And what that means: It will not happen here. The vigil is over in Dodger Stadium. They will now fold the circus tent, pull out the pegs in the ground. The roustabouts will clean out everything, and take the troupe … down to San Diego.”

But the circus leaves behind its dignified ringleader, who at around the age of 80 is still the pinnacle of play-by-play men. The fates may not conspire to give Scully many more spotlight moments on the national stage — though heaven knows they should. But he’ll still fill the airwaves with brilliance and wonder.

Mark Hagerstrom

Nicely done,

oldbrooklynfan

I’m sure Scully would’ve been very enthusiastic, as always, if Bonds would’ve hit number 755. Although he may not have wanted it to happen at Dodger Stadium, he would’ve never shown any sadness in his voice, if Bonds did.