Because we already used Clayton Kershaw’s birthday as an excuse to delve into Part 9 of Brothers in Arms: Koufax, Kershaw, and the Dodgers’ Extraordinary Pitching Tradition (order now!), our series of previews ends on Part Eight: The Bullpen.

Niftily, the position of relief pitcher emerged with the Dodgers around the same time as the Dodger pitching tradition itself took root.

For nearly the entire history of the Dodgers before the end of World War II, when their pitching tradition was incubating, almost every pitcher they used in relief was a moonlighting starter. Only three players in Brooklyn history totaled more than 200 innings in relief before 1940, and two of those were swingmen — Watty Clark and Sherry Smith, who started more games than they relieved. The lone exception, Rube Ehrhardt, did mainly pitch out of the pen from 1926 to 1928, with modest effectiveness.

Starting with Hugh Casey in the 1940s, the game changed, and the Dodgers began transforming pitchers who weren’t cut out to be fulltime starters into pitchers who were primarily relievers, and later purely relievers. In the history of Dodger pitching, they play a supporting but key role, occasionally grabbing headlines—some heartbreaking, some thrilling.

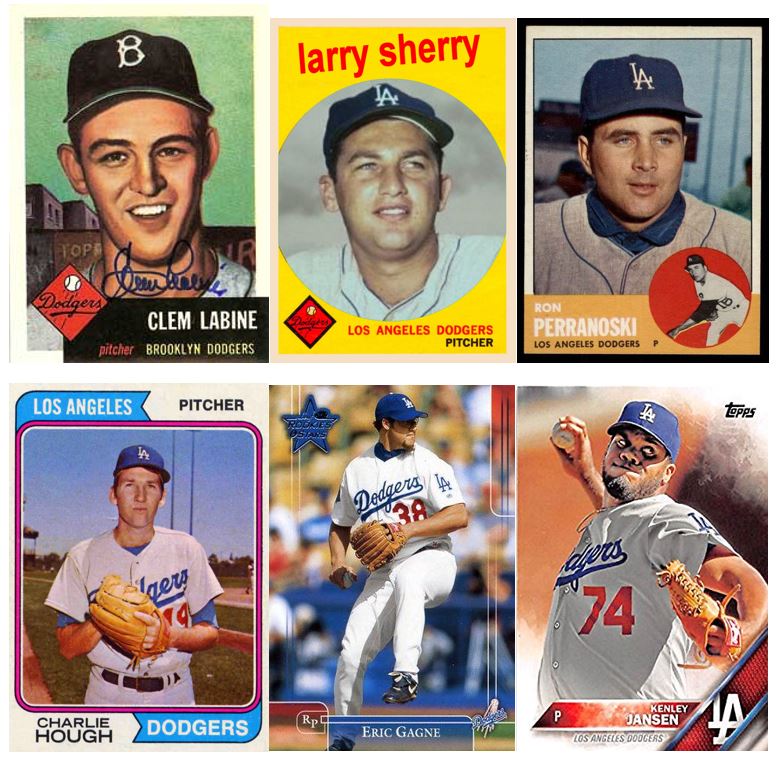

For Brothers in Arms, I crafted profiles on whom I found to be the most significant relievers in Dodger history: Hugh Casey, Clem Labine, Joe Black, Larry Sherry, Ron Perranoski, Jim Brewer, Phil Regan, Charlie Hough, Mike Marshall, Steve Howe, Tom Niedenfuer, Alejandro Peña, Jay Howell, Todd Worrell, Jeff Shaw, Eric Gagné, Takashi Saito, Jonathan Broxton and, of course, Kenley Jansen, whose final exploits have yet to be written. Each carries the story of the Dodger pitching tradition forward in some important way, even in the times they came up short.

Working on the book last year, I fantasized more than once about Jansen somehow following in the footsteps of Labine, who came out of the bullpen to pitch a 10-inning shutout in Game 6 of the 1956 World Series. Or perhaps Jansen would emulate Sherry, who became MVP in the ’59 Fall Classic even though he hadn’t become a full-time major-leaguer until that July.

I reveled in revisiting the career of Perranoski, who from his years of excellence on the mound to his important role as a minor-league pitching coordinator and major-league pitching coach, has had the greatest impact on the organization of any reliever in Dodger history. I laughed at the memories Hough shared with me of how he became a pitcher: “I couldn’t play third, I couldn’t play first, and I didn’t hit very good.” I appreciated giving Niedenfuer, the Ralph Branca of his generation, his proper due for the effectiveness that preceded the devastating October 1985 homers by Ozzie Smith and Jack Clark. With Gagné, I welcomed myself back to the jungle (and to the Mitchell Report). And so on …

In all, it’s a sprightly journey through the history of the men who have come to the Dodgers’ rescue for the past 80 years, quite arguably saving the best for last in Jansen. While the Dodger pitching tradition stands mainly on the starting pitchers, you couldn’t tell the complete story without the bullpen.

And so, there you have it — a look at every section of Brothers in Arms. This obviously won’t be the last time I write about it, but I hope you’ve enjoyed these glimpses of what the book has to offer.

Previously:

- ***NEW BOOK ALERT***: Brothers in Arms: Koufax, Kershaw, and the Dodgers’ Extraordinary Pitching Tradition

- Prologue: Dazzy Vance and the days before the Dodgers pitching tradition began

- Part One: The Kings of Brooklyn

- Part Two: The Two Emperors

- Part Three: The Post-Koufax Generation

- Part Four: The Modern Classicists

- Part Five: El Toro and the Bulldog

- Part Six: The International Rotation

- Part Seven: The Bullpen

- Part Nine: The Magnificent

Comments are closed.