It was drowned out by the Howie Kendrick grand slam, by Juan Soto teeing off on the fattest pitch of Clayton Kershaw’s career, by Anthony Rendon taking a golf swing at a Kershaw pitch near his shins.

It was smothered by a National League Division Series Game 5 that tore the Dodgers and their fans apart.

But before NLDS Game 5, there was Game 2. And in Game 2, there was one inning, arguably one pitch, that speaks as much to the Dodgers’ Job-like journey through the Octobers of the past seven seasons as any other.

* * *

Corey Seager, very quietly, had a very good 2019.

It wasn’t the best season of his young career, but considering he was recovering from both Tommy John surgery and left hip surgery the year before, it deserves to be commended. If you lead the National League in doubles, as Seager did, you must be doing something right. He hit 44, the most by a Dodger in 16 years and five shy of the franchise record.

Seager’s 19 homers in 2019, though only the third-highest total of his career, tied for fourth for the most by a Dodger shortstop ever. At age 25, Seager already has 29 more home runs than any other shortstop in Los Angeles Dodger history, and for the franchise mark, he trails only Pee Wee Reese, who played 16 seasons. Seager has played three full seasons, plus a month in two others.

As 2019 went on, Seager improved. After struggling to a .666 OPS at the quarter pole, Seager registered an .877 OPS for the remainder of the year. In September, he rose to a .939 OPS with seven home runs and 26 RBI, the most RBI by a Dodger in the month of September since Manny Ramirez.

Entering the playoffs, Seager was primed.

* * *

Thanks mainly to six shutout innings by Walker Buehler, the Dodgers won NLDS Game 1, 6-0. Game 2 started poorly, with Kershaw falling behind 3-0 in the first two innings on three two-out hits by Washington.

The Dodgers chipped away. Justin Turner hit a sacrifice fly in front of the warning track in right off Stephen Strasburg in the sixth, and Max Muncy homered off Sean Doolittle in the seventh. The Nationals ran their lead back up to 4-2 in the top of the eighth, punctuating the inning when Max Scherzer came out of the bullpen to strike out the side in the bottom of the eighth.

Still, the Dodgers led the NL in 2019 with 24 wins in their last at-bat, and they were facing a maligned bullpen with an ersatz closer, Daniel Hudson, whom the Dodgers had abandoned the year before.

Turner led off. He took the first three pitches, fastball-strike, slider-ball, fastball-strike. TBS showed Seager, with his cap off, watching from the dugout right before the fourth pitch, a 97 mph fastball over the middle of the plate that Turner flung to right field for a ground-rule double over the short fence.

The next batter was A.J. Pollock.

* * *

Pollock could easily be the headline subject of this post.

There might not be one Dodger fan in 10 to speak to the quality of Pollock’s 2019 season. Like Seager, he started slowly, but following his return from a right elbow staph infection after the All-Star Break, he hit 13 homers in 227 plate appearances with a .885 OPS. In September, he had a three-homer game.

Coming to bat after Turner’s sac fly in the sixth inning of Game 2, with Joc Pederson on second base, Pollock lined sharply to the second-base side of the pitcher’s mound. Strasburg reached out his glove and snagged it, robbing Pollock of a potential RBI single.

Astonishingly, that was the last baseball Pollock put into play in 2019.

With the Dodger Stadium fans already on their feet yearning for a comeback, Pollock took two low-and-outside sliders among the first three pitches, fouling back the one in between for a 2-1 count.

The fourth pitch was the one. Another slider, but belt-high and over the outer edge of home plate. Pollock swung over it, fouling it into the dirt.

Those early sliders set Pollock up. After taking a fastball that missed badly for a full count, Hudson came back with another slider … closer to the plate, but still dipping away. From the moment it left Hudson’s hand, it was heading outside. But after letting the first two sliders go by, after just missing the mistake third slider, Pollock couldn’t resist the fourth. He couldn’t see its evil intent.

Those early sliders set Pollock up. After taking a fastball that missed badly for a full count, Hudson came back with another slider … closer to the plate, but still dipping away. From the moment it left Hudson’s hand, it was heading outside. But after letting the first two sliders go by, after just missing the mistake third slider, Pollock couldn’t resist the fourth. He couldn’t see its evil intent.

He chased. He was done.

At that point in the playoffs, Pollock was 0 for 8 with a walk and six strikeouts. He whiffed in his only three at-bats of Game 3 and didn’t start again, striking out in each of his trips to the plate in the final two games.

A.J. Pollock finished the NLDS 0 for 13 with 11 strikeouts. Everything he accomplished in 2019 was wiped out.

* * *

If fate weren’t hating on the Dodgers, it wouldn’t have shown its hand when Cody Bellinger swung the bat.

Soon to be named the 2019 NL MVP, Bellinger himself was 0 for 3 with two strikeouts in Game 2. Of the six Dodgers to come to the plate in the bottom of the ninth, he was the only one to take a cut at the first pitch. And it was almost magic.

Fending off a 97 mph fastball on the inner half of the strike zone, Bellinger sent a shallow pop fly down the line behind third base. Rendon took off in pursuit — but overran the ball. Falling from the sky, it was veering behind Rendon into fair territory. Tumbling backward, fully extended like a tree cut at its base, Rendon caught the Bellinger quail, the ball peeking out of the top of the webbing of the glove.

Pollock just missed. Rendon just didn’t miss.

* * *

You know that Nationals manager Dave Martinez did not want to face Muncy with the tying runs on base. You know that because, when Muncy then came up as the tying run, Martinez walked him intentionally.

By his own free will, Martinez had put himself in a situation where the man at the plate could beat him.

* * *

That man was Will Smith, who was a rookie, but one who had displayed a preternatural calm in 2019, not to mention the ability to hit walkoff home runs. Smith, in fact, in a few days would represent the Dodgers’ last, best hope, with his ninth-inning drive in Game 5 that fooled a ton of people, including me, into believing it would be an NLDS-winning blast.

Smith already had a hit in Game 2, and you can imagine he had a vision of at least tying the score with another. But he displayed no anxiety, refusing to chase three straight Hudson sliders, before spitting on a fastball to earn his way to first.

The bases were loaded. The tying run was in scoring position. The winning run was aboard.

Here came Seager.

* * *

Corey Seager, in his career, has a .359 batting average with the bases loaded.

Corey Seager choked up on his bat, displaying a solid stem of wood above the knob of the bat and below his hands.

Corey Seager, with a reputation for swinging at the first pitch, watched a 97 mph fastball hit the absolute border of the strike zone. Home plate umpire Jordan Baker punished Seager for his circumspection, calling strike one.

The next pitch was a fraction more attractive, and Seager swung — late. With the game on the line, he was behind in the count, 0-2.

Up to this point, Hudson hadn’t thrown three consecutive fastballs in the inning. With Seager, he threw seven.

Seager fouled away the third and the fourth. But he hadn’t become a robot. When Hudson threw the next two fastballs noticably outside the zone, Seager let them go. The count was even.

After Seager fouled off the seventh straight fastball, Nationals catcher Kurt Suzuki visited Hudson at the mound.

For most of this piece, I needed to consult the play-by-play online to make sure I was rendering things accurately. This next moment, I remember vividly. I was standing in our family room, six inches from the TV screen, bearing down, willing Seager to have serenity to accept the pitch he should not chase, courage to crush the pitch he could and the wisdom to know the difference.

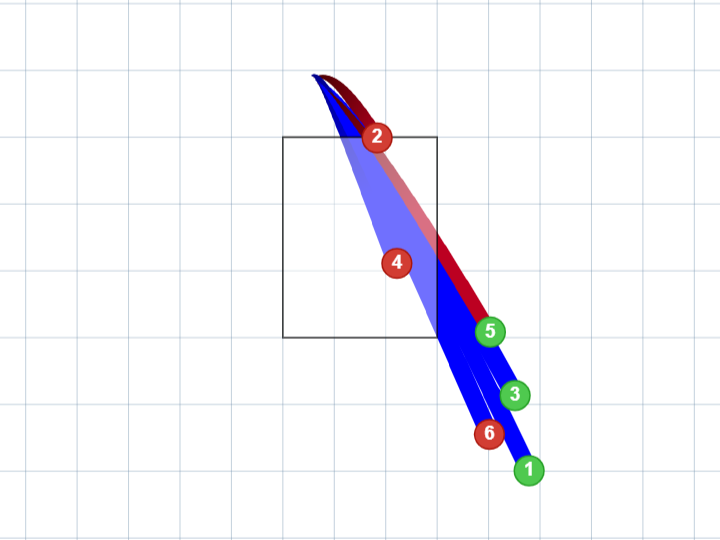

And then Hudson pulled the string. For the first time in the at-bat, on the eighth pitch, Hudson threw a slider, coming in nine miles per hour slower, diving down and in toward Seager’s shins.

Seager had no chance.

* * *

Why?

Is there any other question? It’s as incomprehensible as the nature of the universe.

Why, over the past seven years, have the Dodgers fallen one moment short?

The Dodgers have won 33 postseason games since 2013. They’ve won them early and won them late. They’ve won with hitting, with pitching, with fielding, . They’ve been lucky and they’ve been good.

But always, one hair out of place. One domino out of alignment.

Cody Bellinger was the MVP. A.J. Pollock and Corey Seager were two of the best hitters around in September. In the ninth inning of Game 2 of the National League Division Series, any one of them could have delivered. It didn’t require a miracle.

If the Dodgers had won Game 2, they wouldn’t have needed to play Game 5.

Seager swung and missed at a slider, and spent the offseason hearing his name in trade rumors. Pollock swung and missed at a slider, and the Dodgers went and got Mookie Betts.

The original title of this post was “Corey Seager, a slider and the existential hijinx of October.” (Then I found the photo of Seager blowing a bubble near the start of Game 2, inspiring the headline you see above.) But I remain in love with the phrase “existential hijinx.” That captures, as well as anything I can think of, the feeling of being a Dodger fan the past seven years.

Someone, or something, is playing games with us. Playing with our baseball lives.

I don’t mean the Astros and their 2017 sign stealing, not in and of itself anyway. That is merely a part of the pastiche, a scurrilous manifestation of the art, year after year, of destroying our hopes.

Now in 2020, the Dodgers have placed their Betts, a fabulous addition to a fabulous roster. The Dodgers have ascendant youth, and maybe even some revitalized veterans — Kenley Jansen looked as good Wednesday at Camelback Ranch as he did at any point in 2019.

And they have players in their prime like Seager, who will turn 26 this year in better physical condition than he has enjoyed in the past thousand days.

You can quibble and you can quabble, but the Dodgers have everything they need to win the World Series.

They have had that for quite some time.

But when October arrives, spinning through the air like a leaf from a tree, in all its brilliant but dangerous color, the question might fall upon us again. Why?

Why?

Why?

You might think you have the answer. You don’t. You won’t, until you’re no longer asking the question.

We are passengers on this ride. We are the air inside the bubble.

In facing the coming season, we face the light and darkness all at once, praying for one, prey of the other.

It is, in the end, a grand mystery.

Comments are closed.