The eyes had it.

“He turned the game into a religion,” broadcaster Jaime Jarrín once said. More than a pitcher, Fernando Valenzuela was, of course, a mania. His dusty cinematic background, his cuddly youth and his quietly wry air of mystery fused with his preternatural talent, creating in Los Angeles an immediate sensation and an enduring love affair.

It was nothing that could have been foreseen before the 1980s, least of all by Valenzuela, born the youngest of seven boys and five girls in his family in the Mexican town of Etchohuaquila, near the eastern shore of the Gulf of California, on the first day of November in 1960. Like Sandy Koufax, like Don Drysdale, he didn’t begin pitching until his teens.

“I started playing ball when I was maybe 13,” Valenzuela says. “From that time I liked the game, but I think what I remember more is I had a chance to play with my brothers. We had a large family and I’ve got a lot of brothers, so everyone was playing on the same team. I think that helped me a lot, and they gave me some good advice.”

Valenzuela had older relatives at second base, short, third, the outfield and, yes, on the mound, for which he would have to wait for his own opportunity.

“We had a winter league that played only Sundays, once a week,” he says. “It’s open — no age limit. They told me, ‘You’re gonna play, but you’re not gonna pitch, because you’re too young – your arm is not ready to throw the ball.’ And I think that helped me a lot, because I wanted to pitch – that was my favorite position, but they told me, ‘You’re not ready – your arm is not ready.’

“Probably I was almost 15 years old when I started pitching. That’s when they let me pitch one inning. Little by little – they didn’t let me go all the way and let my arm get tired and throw many pitches. But I had a chance to pitch every week, because it was once every Sunday, so that wasn’t a problem.”

As his talent became apparent, Valenzuela aimed to play professionally — first in Mexico, then in the U.S. — a goal that became more and more realistic once scouts began circling. One of those bird dogs was the Dodgers’ Mike Brito, though partly by happenstance — Brito was scoping a shortstop when he first came upon the precocious southpaw.

The Dodgers officially purchased the 18-year-old Valenzuela’s contract from his Mexican League team in July 1979 for a reported $120,000, of which $20,000 went to the teenager, who passed it on to his family.

“We made one offer,” Dodger general manager Al Campanis later said, “and the Yankees made one. Then we came back and closed the deal before the Yankees had a chance to make another bid.”

Fourteen months later, Valenzuela would be in Dodger Stadium.

His U.S. journey began with three starts before the end of the 1979 minor-league season for Single-A Lodi, allowing three earned runs in 24 innings for a 1.12 ERA — though he walked 13. In the fall of ’79, he went to instructional league, where Brito told him that the Dodgers wanted him to learn another pitch.

Dodger reliever Bobby Castillo (another Brito signee) obliged by showing Valenzuela a pitch that was mostly a relic, whose most famous practitioner, Carl Hubbell, had retired in 1943.

Many remember Valenzuela mastering the screwball almost immediately. Castillo, who died of cancer in 2014, once said that Valenzuela had the proper rotation on the first screwball he threw, and that within a week, the pitch had stopped flattening out. But Valenzuela, who took the pitch with him to Double-A San Antonio in 1980, says it took months to command it (not that “months” is so bad for a prospect still in his teens).

“That was hard in the beginning,” Valenzuela says, “but I kept practicing and practicing, because the Dodgers gave me confidence: ‘Don’t worry, don’t look at the numbers. Whatever score or whatever record you have does not count. We want you to learn that pitch.’ I wanted to stop throwing it – I was a good control pitcher, but I was giving out a lot of walks. But the Dodgers told me not to worry – ‘just keep practicing, keep throwing.’ So I said, ‘Well, if that’s going to put me up there, I’m going to keep working on it.’

Valenzuela recalls a game against Amarillo in the second half of the season that marked the first time he felt he was controlling the screwball, instead of the screwball controlling him.

“That’s when I started to say, ‘OK, I think it’s ready,’ because every time I wanted to throw inside, outside, the ball was there,” Valenzuela says. “Finally, I started to get more and more command, I threw more over the plate and the hitters started chasing bad pitches. Normally, the hitters let it go because they knew it was a ball, but when the hitters started seeing I got more control with that pitch, then I could throw it off the plate and they’d chase it, because they were saying, ‘Now he can throw it for a strike – now where’s it going to be?’”

At the same time, Ron Perranoski, then the Dodgers’ minor-league pitching coordinator, had taught Valenzuela to start busting his fastball inside to counter right-handed batters leaning out after the right-to-left movement of the screwball. The results were devastating. Valenzuela completed seven of his final eight starts in 1980 with four shutouts and didn’t allow a run in his final 35 innings with San Antonio, enabling him to reach 174 innings for the Missions with a 3.10 ERA and 162 strikeouts.

The Dodgers, in the midst of spending a full week tied with Houston for first place in the NL West, matching the Astros win for win and loss for loss, called up the kid to help out their bullpen. It was all circumstance, no pomp — and Valenzuela’s mixed feelings initially nixed the gig in exchange for a Texas League title.

“I didn’t want to come up, because we were in the playoffs,” Valenzuela says. “My manager in Double A, Ducky LeJohn, said ‘You’re going to the big leagues.’ And I said, ‘No, I want to finish here. I want to be a champion here.’”

LeJohn wasn’t sure Valenzuela understood.

“No, they need you there, so you have to go,” Le John said. “If not, we’re going to send another one.”

“OK, send another one,” Valenzuela replied, calling his bluff.

LeJohn folded his hand — and then put down his foot, shipping Valenzuela to nearby Houston to meet up with his new major-league teammates. The youngster didn’t get into a game there, nor on the next stop of the Dodgers’ road trip in Cincinnati. On September 15, 1980, Valenzuela entered his first major-league contest in the sixth inning of what would be a 9-0 loss to Atlanta. He was 19 years and 319 days old.

“If I say I wasn’t nervous, I’m not from this planet,” says Valenzuela, who decades later still remembered his first batter, Bruce Benedict, popping out to center field. “Everybody gets nervous. But not, ‘I don’t want to do it.’ I wasn’t nervous because I didn’t know if I was going to fail. I was just excited – I wanted to just get in the game and just see what would happen, because I didn’t expect anything. I wanted to do my best, and whatever happened was fine.”

After a perfect sixth, Valenzuela fanned Jerry Royster for his first career strikeout to start the seventh, though thanks to errors later in the inning by third baseman Ron Cey and shortstop Derrel Thomas, Valenzuela allowed two unearned runs. He didn’t give up multiple runs in a big-league inning for another eight months.

“When I joined the team, everybody gave me a nice welcome,” Valenzuela says. “The veteran players, they had been playing for many years, so I think that helped me a lot – for that part, I felt more comfortable. I got some friends, and they helped me.”

It was like seeing Christmas thank the children for being so cheerful. In his debut month in the majors, Valenzuela was the unexpected present under the tree, throwing 17⅔ innings with that 0.00 ERA, striking out 16 and walking five. His role quickly grew more critical. On September 27, he bailed out NL Rookie of the Year Steve Howe and Don Stanhouse by pitching the final 1⅓ innings against the Padres for the first of his two professional saves, then was the winning pitcher in back-to-back two-inning shutout outings. Those two wins more or less equaled the number of English words people believed Valenzuela knew at the time.

“They’d say, ‘How do you communicate with Fernando?’” recalls Steve Yeager. “I said, ‘With my fingers. That’s all I need.’”

In the final-weekend sweep of the Astros that forced a 163rd game, Valenzuela came out of the bullpen twice, including two innings in Game 162, helping extend the season but eliminating any chance of him starting the Monday afternoon tiebreaker, as much as alternate history would have happily used him instead of Dave Goltz. Tommy Lasorda later expressed regret that he wasn’t bold enough to start the kid with the division on the line.

“I had no idea what he was like until you catch him for a couple of times,” Yeager says, “and you realize that as young as this young man is, he’s pitching as though he’s five years older.”

“All I’m worried about,” Red Adams said, “is that someone will make him lose 25 pounds, and he’ll be the most physically fit pitcher in Lodi.”

Heading into the 1981 season, it was clear that the Dodgers didn’t plan on keeping Valenzuela from starting much longer — illustrated by their willingness to let Don Sutton go as a free agent. Valenzuela’s maturity continued to stun everyone who came in contact with him, leading to questions about whether he was really as young as he was reported to be. Campanis told reporters he had a copy of Valenzuela’s birth certificate on his desk. “Anyone who doubts it can come up and see it,” Campanis said.

Valenzuela threw well in the spring, with a peak outing of six innings, to punch his ticket for the starting rotation, but it hadn’t crossed anyone’s mind he would take the mound on Opening Day. No rookie ever had for Los Angeles. But then his fellow pitchers started dropping like pawns in an Agatha Christie mystery. Bob Welch developed a bone spur in his right elbow. Goltz had a virus. Burt Hooton was vexed by an ingrown toenail. When Jerry Reuss strained a muscle in his left calf while running the day before the season opened, the Dodgers turned to Valenzuela.

“I was throwing on the side a little bullpen, a little warmup, working out,” Valenzuela remembers. “And when I finished, they told me, ‘We don’t have a pitcher for tomorrow.’ I said, ‘Yes.’ I didn’t wait — I didn’t wait to answer that question.”

Says Lasorda: “I had no concern about it, because I saw him all spring.”

In front of the festive, red, white and blue bunting and 50,511 fans with no idea what to expect, Valenzuela took the mound on April 9, 1981. He began the game more wily than dominant, pitching around baserunners in each of the first three innings, including a couple of early walks, setting the tone for his bodacious career.

“From the first game through the 400 to 500 starts I had in my career,” Valenzuela says, “early in the game, I always tried to be too fine, working in the corners, and that’s when I’d maybe fall behind the hitters. And that made me get in trouble, because pitching like that to big-league hitters is not recommended. My style is not coming up right over the middle of the plate – I had to work in the corners.”

Facing Joe Niekro, the winner of Game 163 the previous October, the Dodgers went ahead in the bottom of the fourth on Steve Garvey’s triple and Cey’s sacrifice fly. Valenzuela battled to hold the lead. With runners on second and third and one out in the top of the sixth, he broke Dodger nemesis Jose Cruz’s bat on a soft liner to short, before inducing an Art Howe comebacker that Valenzuela — soon to be revealed as an expert fielder — flagged on one hop.

In the bottom of the seventh, 24-year-old Pedro Guerrero’s RBI double provided a luxurious 2-0 lead for Valenzuela, who responded by pitching a perfect top of the eighth and retiring Cesar Cedeno and Cruz to start the exuberant ninth. Howe singled with two out, but on Valenzuela’s 106th pitch, Dave Roberts (same name, different DNA from the future Dodger manager) whiffed. It was a screwball.

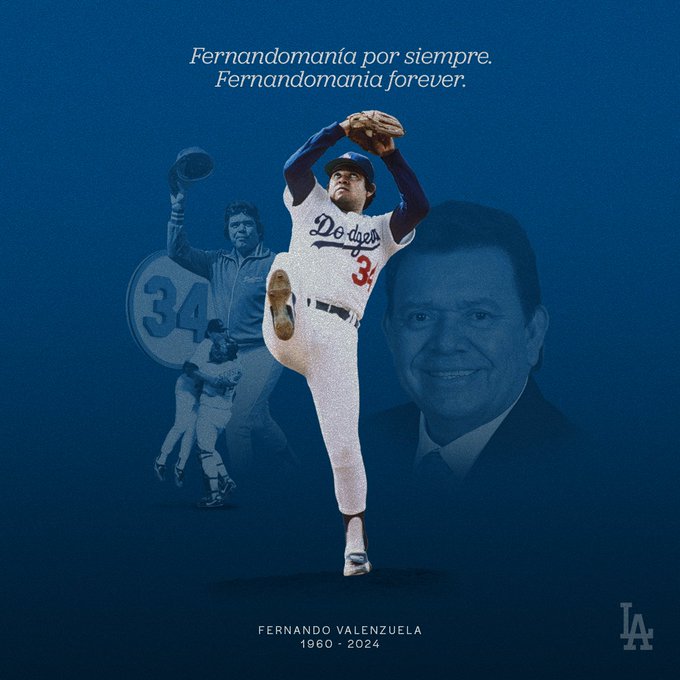

In Dodger Stadium — and soon, throughout Los Angeles, the delight was indescribable. The baseball world didn’t know what to think. The next day, a photograph in the Los Angeles Times showed Valenzuela in his windup, arms high above head, eyes looking up.

Mike Scioscia, himself only 22 with 54 big-league games to his name, was making his first Opening Day start as well and caught Valenzuela’s shutout, as well as all but two of his starts in 1981.

“Even though he was 20 years old, he was pitching baseball like a veteran,” Scioscia says. “Just the whole experience of when you would catch Fernando, just the way he was in command and control and never got flustered out there, all the things that are important in a championship-caliber pitcher, that was him.”

Valenzuela’s second start came April 14 in frigid Candlestick Park. In the eighth inning of that game, he finally allowed his first MLB earned run, on a two-out double by Larry Herndon and RBI single by Enos Cabell, in what was otherwise a masterful 10-strikeout, 7-1 victory over the Giants. Adding in his San Antonio scoreless streak, it was the first earned run he had allowed in 69⅓ innings.

“Fernando’s way of doing things was working around the screwball,” Reuss says. “Fernando’s pitches, if you grade ’em out just on velocity or movement, they may be average, maybe a little bit better. But where his numbers really jumped were in his mixing of pitches and his ability to be just as deceptive as he was. That’s what Fernando was all about. It wasn’t about his stuff. It was about deception.”

Lasorda took quick advantage of his amazing new talent. Valenzuela made each of his next two starts on three days’ rest and threw back-to-back shutouts, first 2-0 at San Diego, then 1-0 at Houston, where he drove in the game’s only run with an RBI single off Sutton.

“When he had to make pitches, he made them,” Sutton said after the game. “With men in scoring position, he never gave one of our hitters a good pitch to hit.”

In the first two weeks of the 1981 season, Valenzuela had thrown 36 innings and struck out 36, while allowing only the one run. By this time, the media frenzy was beginning, with pregame sessions becoming press conferences. “This is where we get set to say goodby to Valenzuela’s childhood,” wrote Mark Heisler of the Times. A day later, the headline on Scott Ostler’s column was one word, appearing in print for the first time: “Fernandomania.”

“I was excited,” Valenzuela recalls. “It was fine — hard, at the same time. On the field, I was fine. Off the field, after the games – sometimes people or the media didn’t understand – they wanted the interview right away, and I had to work, I had to be with the team. In that time, that was the hard part, but when I went on the field, that was exciting, because I knew what I had to do. I had a lot of confidence in my stuff.”

“The Mexican people in Los Angeles were clamoring for an idol,” Jarrín says. “When he started pitching in 1981, not only Mexicans, not only Latinos but the Anglos also took notice of this kid, a little bit chubby, long hair, who couldn’t speak any English. The American people fell in love with him. Everybody.”

Rather than deploy a teammate or coach like Manny Mota to translate, vice president of public relations Fred Claire asked Jarrín to do so. On road trips, Jarrín and Valenzuela began flying to the next city a day ahead of the team in preparation for the next media onslaught, and when Valenzuela pitched, Jarrín would leave the broadcast booth in the eighth inning to be ready for the postgame Q&A from dumbstruck reporters.

“He was always very reserved,” said Jarrín, who became a mini-national celebrity in the process. “In 1980, the writers didn’t pay much attention to him because he was just a member of the bullpen. Then ’81 started, and everything became a madhouse there. But he was always a very reserved person, very private person. Many people wondered if he knew exactly where he was and what was happening around him — and he knew exactly. Extremely sharp guy, very intelligent.”

With his teammates, Valenzuela was generally quiet, but his sense of humor snuck up and delighted them.

“Fernando liked to play around,” Reuss says. “Liked to play jokes too. Did anybody tell you about his lasso? He made a lasso out of clothesline, maybe he had a couple of different ones. And when somebody wasn’t looking — they’d put their foot up or cross their legs and sit comfortably on the bench, in a conversation or watching the game — he’d get his lasso out and just like a cowboy, he’d spin it over his head and catch somebody’s foot and then yank it off their knee.”

The night the “Fernandomania” headline appeared, Valenzuela pitched his fourth shutout of the month, 5-0 over San Francisco — while going 3 for 4 to raise his batting average to .438. His career ERA at that moment was 0.14.

“We had no idea that he would rise as fast as he did,” Hooton says, “but it was fun to watch. He handled it amazingly well. Here’s a kid that was 20 years old, and he’s got to do press conferences before every game he pitches. He’s got a whole half a world watching everything he does. And for a 20-year-old kid to handle things the way he handled, it was pretty remarkable — and then still go out and pitch the way he pitched.”

“It was a little bit like when you throw a rock into water and you see it splash,” says Reuss. “Fernando was the splash. I was one of the ripples on the wave. I was one of the ones close up, so I saw it happen right there in front of me.”

In his sixth start of the season and first start of May, Valenzuela gave up his second run and his first lead of the season when Montreal’s Chris Speier tied the game at 1 in the bottom of the eighth with an RBI single. Valenzuela finished the ninth inning, then came away a winner when Los Angeles scored five times in the top of the 10th. In his next start, Valenzuela returned to his familiar ways, making a 1-0 lead stand up in New York for his fifth shutout (with 11 strikeouts). He then improved to 8-0 on the season when, after Speier and Andre Dawson hit the first home runs ever off him, sending the game into the bottom of the ninth tied 2-2, Guerrero hit a walkoff blast to win it.

It’s tempting to believe that Valenzuela had arrived in the big leagues fully formed, but he continued to be a student.

“Fernando was very coachable,” Scioscia says. “And I think that he was trying to absorb knowledge and have an understanding of just the path he needed to be as good as he could be. Ron Perranoski had a positive influence on him. But everything from game plans to how to work in between starts, Fernando absorbed information like a sponge.”

The scope of Valenzuela’s impact could be seen not only at Dodger Stadium but throughout the community — on May 17, thousands attended a Dodger community clinic with Valenzuela in East Los Angeles — and indeed, across the country.

“I’m half Mexican-American,” says the historian, Eric Enders, an El Paso native, “and the community I grew up in is 80 percent Mexican-American, and everybody in town was so excited about Fernando. The first memories I have of him was that everybody wanted to talk about him, not only Dodger fans, not only baseball fans even. I remember at all our family gatherings my tío Manuel, who didn’t care about baseball one bit, but he would always ask me, ‘How’s Fernando doing? How’s Fernando doing?’ And we’d talk about that. It just seemed to really galvanize this community, even a community that has nothing to do with Los Angeles, that’s 900 miles away. People were just really proud of him.”

Valenzuela’s grip on those hearts held firm even after his stranglehold on baseball loosened. On May 18, in his ninth start, there was another shutout, but this time, it was Los Angeles on the scoreless end, with Valenzuela giving up four runs (on three hits and two walks) in seven innings for a loss — an actual loss. Despite throwing an 11-strikeout complete game on June 1, Valenzuela had become mortal. In his final six starts before players went on strike in mid-June, Valenzuela had a 6.16 ERA in 38 innings. He started and pitched a shutout inning for the NL in the All-Star Game after the labor dispute ended, but struggled more in his first two starts for the Dodgers in August.

A few years earlier, baseball had been visited by a charismatic phenom in Tigers rookie Mark Fidrych, who threw 24 complete games and led the AL in ERA in 1976 — talking to baseballs all the while — only to be out of the majors within five years. There were those who thought Valenzuela was about to vaporize even more abruptly. But Valenzuela rebounded — and in the process, helped seal his NL Cy Young and Rookie of the Year honors — by finishing his season with a 1.85 ERA in his final nine starts, leaving him with a 2.48 ERA (135 ERA+) and league-best 11 complete games, eight shutouts and 180 strikeouts. In the closest NL Cy Young vote ever at that point, Valenzuela edged Tom Seaver (2.54 ERA, 140 ERA+), with Steve Carlton (2.42 ERA, 151 ERA+) third. Nolan Ryan, who led all pitchers with a 1.69 ERA and 195 ERA+ but pitched the fewest innings of the top quartet, finished fourth.

“In hindsight, you get some room in your rear-view mirror and you kind of get some perspective,” Scioscia says. “And looking back, it was unbelievable how all the stars aligned, that this young superstar pitcher from Mexico is pitching in L.A. And the immense amount of pressure that possibly could have built on his success as he pitched shutout after shutout — he was just marvelous that year — diffused because he was just a kid playing baseball. That’s what he felt.”

Valenzuela hardly stopped there. With his veteran teammates on a mission to finally win their first World Series for Los Angeles, Valenzuela had a superb postseason, beginning by allowing two runs in 17 innings in the NLDS against the Astros, including a 2-1, complete-game four-hitter in Game 4. In the NLCS against the Expos, Valenzuela dropped Game 2, 3-0, but got a second chance in the decisive Game 5.

Montreal jumped ahead against him in the first inning, when Tim Raines doubled, Rodney Scott reached on a fielder’s choice and Raines scored from third on a double-play grounder by Dawson. Valenzuela himself tied the game with an RBI grounder in the fifth, and allowed only three other baserunners until the ninth inning, retiring 18 of 19 at point, before Rick Monday hit his unforgettable two-out home run to give the Dodgers a 2-1 lead and ultimately the pennant.

Valenzuela allowed six baserunners in 8⅔ innings. In his first four postseason starts, he had a 1.71 ERA. His fifth start was nothing like the first four — and yet, it was incredible.

The Dodgers lost the first two games of the 1981 World Series, giving them six straight losses to the Yankees in postseason play dating back to the ’78 Fall Classic. Minutes after Valenzuela took the Dodger Stadium mound in Game 3, Cey’s first-inning homer gave the Dodgers a 3-0 lead, but a rocky Valenzuela, who had walked two in a scoreless first inning, wobbled more.

Bob Watson hit the second pitch of the second inning over the wall in center. So concerned were the Dodgers with Valenzuela that when Rick Cerone followed with a double, Goltz began warming up in the bullpen. Valenzuela had faced six batters to this point. One out later, Larry Milbourne singled home the Yankees’ second run, and in the next inning, Cerone hit a two-run shot to left-center off a screwball to give the Yankees the lead.

“This might be the worst game I’ve ever seen Valenzuela pitch,” Vin Scully said on the national radio broadcast.

Through three innings, Valenzuela had already thrown 71 pitches, New York bombarding him with 10 baserunners to go with the four runs. But keen to preserve their lead, the Yankees made a fast pitching change, pulling Dave Righetti for George Frazier when Garvey and Cey reached base to begin the bottom of the third. Lasorda wasn’t beyond making a quick move himself, sending Scioscia up with two out to bat for Yeager.

Scioscia grounded out to end the inning, leaving Valenzuela in the on-deck circle, holding perhaps one more chance to right his ship. With two out, he issued his fourth walk, to Dave Winfield, before surviving a Lou Piniella liner to left. Valenzuela batted for himself in the bottom of the fourth, only to give up a leadoff double to Watson in the fifth that sent Tom Niedenfuer to get warmed up.

“He was struggling pretty bad,” Lasorda says. “But I said, ‘No, I’m not taking this guy out. I’m leaving him in.’ I’m depending on this guy. I believe in him, and I told him, with as much Spanish as I could speak, ‘I’m leaving you in here because you can work your way out of here and pitch this game.’”

For the second time in five innings, Valenzuela walked Milbourne intentionally to get to the pitcher’s spot and escape the inning. In the bottom of the fifth, the Dodgers tied the game on Guerrero’s RBI double, then took the lead on a run-scoring double-play grounder by Scioscia. When Valenzuela batted for himself with a runner on third, having thrown 95 pitches in five innings, the crowd, still fully behind him, roared with approval.

Valenzuela grounded out. He then walked Randolph to start the sixth inning, but after another visit to the mound by Lasorda, with Niedenfuer and Steve Howe warming up in the bullpen, Scioscia threw out Randolph trying to steal, helping Valenzuela finish his third consecutive shutout inning.

“Sometimes, you’re not gonna have the best stuff,” Valenzuela says. “I kept fighting and fighting, but my control was the problem. Like I mentioned before, sometimes early in the game, that’s when I had a problem, because I’d try to be too fine. So if I didn’t have command on any pitch, that’s when I’d get in trouble, and that happened in that game, that third game of the World Series.

“But I started not using a lot of screwballs. I started using fastballs inside on the hands of right-handers, and they started hitting but in front, pulling foul balls, and that’s the only way they could do it – hit it hard, but foul balls. And after that, I came up with the screwball. And that’s when it started working. “

The remainder of the game doubled down on suspense. In the seventh, Baker flagged down a Watson drive to the left-field wall. In the eighth, after Aurelio Rodriguez and Milbourne singled — the 15th and 16th baserunners off Valenzuela — Cey spectacularly dived to catch a Bobby Murcer bunt in foul territory and then doubled Milbourne off first, then made a difficult play on a Randolph grounder and tagged Rodriguez running from second to third.

One inning remained.

“The whole year was amazing,” Jarrín says. “The whole year was fantastic, and the beginning was unbelievable. But then everybody believes, as I do, the best game he ever pitched was in the World Series against the Yankees. He didn’t have his best stuff, and he was in trouble during the whole game, and Lasorda went to the mound several times, but Fernando, he wanted to finish. That was one of his trademarks — he wanted always to finish what he started. He didn’t care if he had thrown 130, 135 pitches. He wanted to close. And that game against the Yankees, he didn’t have his best stuff but he was so valiant. He came through unbelievably.”

In the ninth inning, Jerry Mumphrey grounded out. Winfield flied to right center. Piniella took two balls before a called strike and a foul evened the count. On pitch No. 147 from Valenzuela, Piniella swung and missed.

“I don’t know how many pitches he threw,” Scioscia says. “But he was just as fresh at the end of the game as he was at the beginning.”

“This was not the best Fernando game,” Scully famously said at the end of his broadcast. “It was his finest.”

The victory was the first of four straight by the Dodgers, depriving Valenzuela of what would have been a Game 7 start at Yankee Stadium but more than compensating him with a World Series celebration.

“That was an exciting game,” Valenzuela says. “The two best moments in my career – I think the first game I started against Houston on Opening Day, and that game, the World Series — I think those were my best moments.”

Amazingly, Valenzuela’s big-league life was only 13 months old. It had been less than 2½ years since he first came to the United States. He turned 21 eight days after the World Series ended. The rest of his career lay before him.

“I put in my head, ‘That’s only one season,’” he says. “It’s easy to reach the big leagues, but to stay in the big leagues and do it successfully, that’s the hard part. So I had to keep going, had to keep working. The season was in the past, the World Series was in the past, and so I had to be looking forward.”

Barely taking time off, Valenzuela pitched for Navojoa in the Mexican Winter League, hurling a no-hitter in January 1982, before beginning the first year of the rest of his big-league life.

While lacking the pyrotechnics of his rookie year, Valenzuela went 19-13 with a 2.87 ERA (122 ERA+) in a sophomore season that was arguably more impressive, if perhaps naive, in its endurance. Still only 21, Valenzuela pitched nearly 100 more innings, shooting up to a career-high 285, including 18 complete games.

“He came to the mound like a general going to battle,” Jarrín says. “He was unbelievable.”

Lasorda wasn’t quick with a hook, and when it did come near him, Valenzuela ducked away.

“In the ‘80s, that’s the way we played,” Valenzuela says. “I had a lot of confrontation with Tommy, because he’d tell me ‘You’re up over 100 pitches already.’ I’d say, ‘No, I’m fine, I want to stay in the game, I want to finish the game.’ So I don’t know if I would change anything, because that’s the way I liked to play. But it’s hard to compare now and the old days. I’d have to play now to see how my head would change.”

This was also the year that Valenzuela hit the first of his 10 big-league home runs, on August 25 at St. Louis. In his MLB career, Valenzuela batted .200, and his 158 hits while pitching for the Dodgers (not including his 5-for-15 pinch-hitting record, a stat he knows by heart) trailed only Don Newcombe, Drysdale and Hershiser.

Ask Valenzuela to talk about his pitching accomplishments, and he’s a minimalist. Ask him about his hitting, and a steady flow of words floods his shyness.

“For shutouts, you need defense,” he says. “Sometimes good defense will save you a run. On a home run, nobody helps you out. Really for me as a pitcher, a lot of good things happened when I was on the mound. But at the plate, things didn’t happen like that every day. So hitting a home run, that was more exciting for me. When you hit in the sweet spot in the right spot of the bat, you’re not gonna feel anything on your hands. You’re gonna make contact, and the ball’s gonna fly. That’s the best feeling, as a hitter, not only when you hit homers but when you hit it solid.”

By this time, Valenzuela had a strong reputation in all aspects of the game. Despite his teddy-bear physique, he was obviously an athlete, and an fundamentally sound one at that. No one was a better decision-maker on the field than Valenzuela.

“You have to anticipate before the batter hits the ball,” he says. “So that helped me out a lot — just to be ready and thinking in that situation. If the ball is coming up to me and I have first and second, where do I go? I go third or go first or go where? No, I go for the double play, second to first.”

When the Dodgers ran out of position players in their 21-inning, two-day win at Wrigley Field during the summer of 1982 and Valenzuela had to play outfield, it was just an extension of his normal routine between starts. “I liked to go to the outfield and practice catching fly balls – you never know,” he says. “You’ve got to be ready for anything. But that was exciting.”

The rumbliest of Valenzuela’s first seven seasons as a starting pitcher came in 1983, though as such seasons go, it wasn’t bad: 257 innings, 3.75 ERA (96 ERA+), plus the Dodgers’ only victory in the NLCS, when he threw eight innings of one-run ball against Philadelphia. He recalibrated to a 3.03 ERA (116 ERA+) in 1984, with the most memorable start coming May 23 at Philadelphia, when he took the mound following a pregame thunderstorm and struck out a career-high 15 — the most in a game by a Dodger since Koufax — outdueling Steve Carlton in a 1-0 shutout in which he drove in the only run.

“I learned a lot from Fernando, just the way he went about from day to day,” says Rick Honeycutt, who pitched for the Dodgers from 1983-87 (3.58 ERA, 100 ERA+) before becoming their longtime pitching coach in 2006. “His personality and persona just never changed. You wouldn’t know if he had thrown a no-hitter or if he had given up five or six runs in his start. He was just upbeat and happy every day, and always interacted with with the players and the other pitchers with a smile on his face. I learned that you just give everything you have and then let that game roll off your back and go be ready for the next game. It was an eye opener for me, how you should take every day and just enjoy it and work hard and just have fun here.”

Fernandomania II: Electric Boogaloo returned to Los Angeles in 1985, when Valenzuela started the season with 41 consecutive innings without allowing an earned run, before Tony Gwynn hit a solo homer in the ninth inning of a 1-0 Padres victory at Dodger Stadium on April 28. Crazily, that left Valenzuela with a 0.21 ERA but a 2-3 record in a month in which he pitched two shutouts, but twice lost 2-1 games on unearned runs.

No game that season, however, drew more attention than the night of September 6, when he faced off against baseball’s newest 20-year-old sensation, Dwight Gooden. The Mets right-hander dazzled Dodger Stadium, striking out 10 in nine shutout innings. Valenzuela two-upped him, pitching a career-high 11 shutout frames, in a game the Dodgers lost in the 13th. A season-high Chavez Ravine crowd of 51,868 gave Valenzuela two standing ovations.

He finished the regular season with a career-best 2.45 ERA and 141 ERA+ in 272⅓ innings. That October, Valenzuela made the final two postseason starts of his career. Facing St. Louis in the NLCS, he was a Game 1 winner with 6⅓ innings in a 4-1 victory, pitching with the veteran maturity that made it easy to forget he was, unbelievably, still not yet 25 years old.

“We had a meeting before the game to talk about how to pitch their guys, where to throw, what to throw, all that,” said Enos Cabell, the Dodger first baseman that day. “Fernando went out there and threw ’em exactly like we talked about. Exactly! I couldn’t believe it.”

In Game 5, Valenzuela allowed two runs and lasted eight innings and 132 pitches despite walking an NLCS-record eight, leaving with the score tied before Ozzie Smith’s walkoff homer off Niedenfuer floored Los Angeles.

Though Valenzuela’s ERA declined in 1986 to 3.14 (110 ERA+), he remembers the year most fondly, because he broke the 20-win barrier, going 21-11, along with a career-high 20 complete games. He finished second in the NL Cy Young voting and won his first Gold Glove Award. His 20th victory was a two-hitter at the Astrodome, the let-them-playpen where he first put on a Dodger uniform and where, two months earlier, he stole the All-Star Game by striking out the first five batters he faced — Don Mattingly, Cal Ripken Jr., Jesse Barfield, Lou Whitaker and Teddy Higuera — to begin three shutout innings.

“A lot of good things have happened to me in that stadium,” Valenzuela says. “I’ve got good memories. For the hitters, it’s batting .300. For pitchers, the magic number is 20 – to win 20, I think that’s the greatest.”

Valenzuela’s 1987 season began well, but a lack of dominance and command began to catch up to him, and he finished with a 3.98 ERA (101 ERA+), allowing 382 baserunners — the most by a Dodger in 46 years — in 251 innings. The same pattern of a solid start and midseason struggle returned in 1988 (the year he began wearing glasses on the mound), only it got worse. On May 22, he was knocked out of a game in the second inning for the first time ever. On June 25, he gave up three first-inning homers to the Reds and left before he got the third out.

Finally, on July 30, he called the trainer to the mound during the fifth inning of a start against the Astros. After taking 255 consecutive turns in the Dodger starting rotation, Valenzuela went on the disabled list on the last day of July with a stretched left anterior capsule, which contained the ligaments that stabilized his left shoulder. The 26-year-old Valenzuela’s fastball had lost between 5 and 10 mph, and his screwball was ineffective.

“When he would bring the arm up to throw, he would feel pain,” Dr. Frank Jobe said at the time. “Then, he would drop the shoulder down to protect it. It stiffens the muscles in the shoulder. When you drop your arm, you lose your fastball, and then he’d try to throw too hard to compensate.”

Valenzuela came back September 26 to test his ability to pitch in the playoffs, and actually started the game in which the Dodgers’ clinched the 1988 NL West title, allowing a two-run homer in three innings while on a 60-pitch limit. A four-inning relief outing with no earned runs October 1, in which he earned his second career save, was encouraging on the surface, but even Valenzuela, whose career playoff ERA was exactly 2.00, said he didn’t trust himself enough to pitch in critical games, and his season ended with his absence from the postseason roster.

“It was extremely hard for him not to be able to help the ballclub,” says Jarrín, who recalled asking Valenzuela why he never wore his 1988 World Series ring.

“Because I didn’t do anything,” Valenzuela told him. “I don’t deserve that ring.”

“Come on, Fernando,” Jarrín replied. “Come on.”

“No, no,” Valenzuela said. “I never wear that, because I was not helping the ballclub.”

Before his 28th birthday, Valenzuela had thrown more than 2,000 innings as a Dodger. The wear and tear was enormous, reflected not only in the innings but the number of pitches he threw within them. Returning for his 10th season in the majors in 1989, Valenzuela knew he had to reinvent himself, according to Scioscia.

“He understood what he needed to do to be successful, and he found ways to do it,” Scioscia says. “So he came up with a little cut fastball to help him get inside on right handers more, which would keep the outside corner still open for a screwball or his fastball. He understood about changing speed — he always changed speeds great, but he didn’t have the 91 mph fastball anymore, so he had to try and adapt, and actually had some pretty good seasons after he hurt his arm.”

After a second-inning May 4 knockout that left his ERA at 4.91, Valenzuela had a 3.17 ERA the rest of the ’89 season, finishing with a 3.43 ERA (100 ERA+) in 196⅔ innings. On June 3, he returned to position play, taking over first base while Eddie Murray moved to third in the Dodgers’ 22-inning game against the Astros, another memorable day for Valenzuela in Houston. Third baseman Jeff Hamilton was on the mound, throwing upward of 94 mph in his bid to keep the Dodgers alive. Valenzuela caught a pop fly in foul ground for Hamilton’s first out in a perfect 21st inning, then was on the receiving end of a toss from Hamilton for the first out in the 22nd. But with runners on first and second and two out, Astros shortstop Rafael Ramirez lined one the opposite way.

“I jumped,” Valenzuela says, “and it tipped my glove and went into right field. So close. And it scored the run. And (Hamilton) was so mad. He was pissed. And I went to see him and I said, ‘You know what, that’s the way we feel when we lose games too – so don’t worry.’”

In 1990 came the capstone of his Dodger career. It had been an uneven year. His ERA was as low as 2.68 in mid-May, then rose to 4.09 two weeks later. To start June, he fanned 22 in 27⅔ innings with a 2.28 ERA, before taking a 10-hit, eight-run beating June 24 at Cincinnati. He was inconsistent and unpredictable from game to game.

The day of his next start, June 29, former teammate Dave Stewart was throwing a no-hitter for Oakland.

“They told me had a no-hitter for six innings,” Valenzuela says, “and I said, ‘That’s good, that’s great.’ So I went to do my routine, my preparation, for the game. I kept going and going, and then when I was walking to the bullpen, walking right next to the video room, they told me, ‘Dave Stewart just got a no-hitter.’ I said, ‘It’s good for him. You guys were watching?’ They said, ‘Yeah.’ ‘So you guys were watching one on TV, now you’re going to watch one live.’ They said, ‘You’re crazy,’ and all that.”

Left fielder Stan Javier’s first-inning error enabled the only baserunner against Valenzuela until one out in the seventh, when former teammate Guerrero and future Dodger Todd Zeile drew consecutive walks, but Valenzuela retired the next two batters to escape the jam. As the night’s drama mounted, Lasorda pierced the tension and drew laughs by yelling for Mickey Hatcher to pinch-hit for Valenzuela in the bottom of the eighth, but there was no way El Toro wasn’t going out for the final battle.

After fanning Vince Coleman on a called third strike to start the inning, Willie McGee walked on four pitches, bringing Guerrero up to the plate.

“We were teammates for a long time, for eight seasons,” Valenzuela says. “I thought that he wasn’t going to be that aggressive, because I was throwing cutters right on the hands, but he was swinging hard. So I said, ‘He’s serious.’ So I kept the ball right there on the hands, and that’s when he got that ground ball right back there to the middle. I’m not sure if that hit tipped my glove or not, if it took a little bit of velocity off that ground ball. It surprised me.”

Less surprised was second baseman Juan Samuel, who had shaded toward second base before the pitch and saw the ball come almost exactly to him. Samuel stepped on second and threw to first, and Guerrero, on his 34th birthday, was doubled up for the final out.

“If you have a sombrero,” exclaimed Scully, in what might have been his most famous post-1988 call, “throw it to the sky.”

Unfortunately for Valenzuela, the sky was no longer the limit. If the no-hitter capping a strong June seemed to show that Valenzuela was back, an 8.40 September ERA spoke otherwise, leaving him with a 4.59 ERA (80 ERA+) in 1990. That November, he became a free agent, but other teams were wary of giving up draft-pick compensation to sign him, and he returned to the Dodgers on a one-year deal but without a guaranteed spot in the 1991 starting rotation — nor a contract guaranteed at its full value unless he was on the Opening Day roster.

Throughout Spring Training, Valenzuela’s future was a huge question. Before 27,000 in a mid-March exhibition in Monterrey, Mexico, he pitched five shutout innings and hit an RBI single, a vintage and emotional day for everyone in attendance. But in other games, opponents pounded him. On March 28, 12 days shy of the 10th anniversary of his first Dodger start, the Dodgers parted ways the author of Fernandomania.

“I think that’s part of the game, part of the business and all that,” Valenzuela says. “I understand that. The only hard part for me was they told me about a week before the season started. By that time, all the teams, they’re already ready to go. I think that’s the only thing that hurt me a little bit, because I didn’t have any other team, any other options. If they had said, ‘OK, we don’t have a plan for you, we’ll let you go to find another team, early in Spring Training,’ that’s (a better) choice for me.”

In his Dodger career, Valenzuela threw 2,348⅔ innings (seventh in team history) with a 3.31 ERA (107 ERA+), 1,759 strikeouts (sixth in Dodger history), 915 walks (second, behind Don Sutton), 107 complete games (11th) and 29 shutouts (tied with Dazzy Vance for sixth).

Valenzuela was 30 years old, the age of Koufax when he threw his last pitch. But Valenzuela continued for six more years. His initial comeback attempt, with the nearby Angels in 1991, generated much attention but lasted only two big-league starts, and he didn’t pitch in the majors at all in 1992. However, coming back yet again in 1993, this time with Baltimore, he threw 178⅔ innings in 31 starts. He remained inconsistent, as a 4.91 ERA (91 ERA+) signaled, but had several strong performances, including a six-hit shutout three years and a day after his Dodger no-hitter. With San Diego in 1996, he threw 171⅔ innings with a 3.62 ERA (110 ERA+).

His major-league career finally ended on July 14, 1997 with St. Louis, though as late as 2006, at age 46, he made 11 starts for Mexicali in the Mexican Winter League. Moving on to become a Dodger broadcaster, Valenzuela professes to like all sports, but his love for baseball never wavered.

“It’s almost – I don’t want to say perfect – it’s almost a perfect game,” Valenzuela says.

Heavenly, even.

Comments are closed.