As we move forward in previewing the May 1 release of Brothers in Arms: Koufax, Kershaw, and the Dodgers’ Extraordinary Pitching Tradition (pre-order now!), we leave behind “The Two Emperors” and find out in Part Three how the Dodgers transitioned on the mound from the 1960s to the 1970s without Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale.

Three men who were teammates of the Hall of Fame duo — along with one extraordinary pitching coach — paved the way.

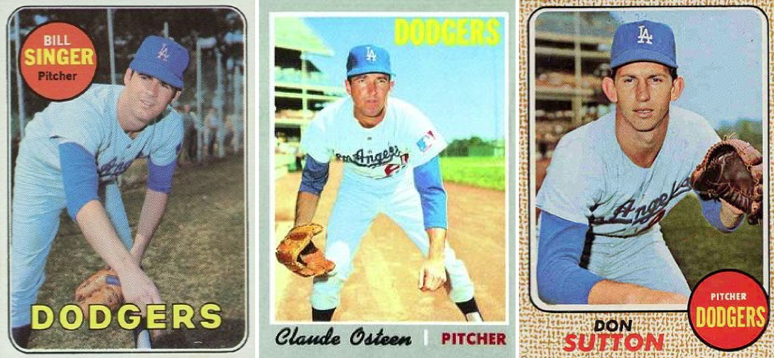

Here’s a little-known fact: On the first Opening Day of the post-Koufax era, in 1967, the Dodgers’ starting pitcher was Bob Miller, who had made zero starts the year before. But soon enough, the pitcher who filled Koufax’s spot in the rotation was Bill Singer, a promising right-hander who was a pioneer in his own right. Thoracic outlet surgery, which requires the removal of a rib, is common enough today that four current members of the San Diego Padres have had it. In the fall of 1966, as you’ll read in Brothers in Arms, a 22-year-old Singer took the risk of becoming the first.

“I was the original,” Singer said in an interview with me. “I was the Tommy John of that.”

While Singer was new to the Dodger rotation in ’67, Claude Osteen was already a stalwart member. By far the most significant pitcher acquired from outside the organization in the 1960s, Osteen had a crucial victory in Game 3 of the 1965 World Series, after the Dodgers had lost their first two games. But Osteen’s value stretched far beyond those postseason heroics, as he followed his debut Dodger season with eight more, pitching at least 235 innings in each of them. The left-hander ranks 15th in franchise history in wins above replacement and eighth in Los Angeles.

“I was always in great shape,” he said in his interview. “I worked hard. I ran — back then, running was the key — and I never varied from my routine. If I was going bad, I ran; if I was going good, I ran. And so I had a lot of stamina, and I had to pitch with my brain, because I couldn’t overpower anybody.”

Then, of course, there’s Don Sutton — 21 years old when he made his big-league debut during Koufax’s final season, 43 years old when he pitched his last game in 1988. Sutton’s grand accomplishments during a Hall of Fame career are shorthand for many Dodger fans, but lost in the 324 wins and 3,574 strikeouts is an incredible amount of spiky news and numbers throughout those 23 seasons, specifically the 16 with Los Angeles.

It’s common to think of Sutton as a compiler, but he also had extraordinary stretches worthy of a “-mania,” and Brothers in Arms puts in perspective the level of his talent. At the same time, Sutton was no simple-minded man, and his mental and emotional journey through his years as a Dodger offers a much more compelling saga than today’s fans realize. From the book …

… for all his steadfast ability, Sutton’s personality and presence in Los Angeles revealed themselves to be as complicated as his pitching repertoire. Longer than any other Dodger pitcher, he was the centerpiece of serious trade talks. Several times, newspapers reported his departure as imminent. These weren’t just wild rumors—often, Dodger executives and Sutton himself openly discussed the possibility of him leaving town. He frequently wondered aloud if the grass were greener elsewhere, either playing for another team or moving onto another profession, namely broadcasting. In practically the same breath, he unabashedly admitted how much he valued his rising place in the Dodger record books. He could be charming and unnerving in the same conversation.

In Sutton’s 1998 Hall of Fame acceptance speech, he went out of his way to thank Red Adams, the baseball lifer who was pitching coach for most of Sutton’s tenure on the mound. “No person ever meant more to my career than Red Adams,” Sutton said. “Without him, I would not be standing in Cooperstown today.” Sutton was far from alone in his praise. One of the great surprises for me in doing this book was how prominent Adams (a familiar but largely silent figure from my childhood) was in the narrative of the Dodger pitching tradition. The introduction to Part Three of Brothers in Arms pays tribute to Adams for taking the role of the pitching coach in Los Angeles to previously unseen levels.

These behind-the-scenes stories help explain why the Dodger pitching tradition is not just in our imagination, and I’m thrilled to have put them together.

Previously:

Comments are closed.