The amazing life of Tommy Lasorda ended Thursday at the age of 93.

I was just becoming a baseball fan when he became the Dodgers’ manager in September 1976. Nearly 40 years later, I would find myself in the Dodger press box cafeteria at lunch as an employee and introducing my two sons to Lasorda, and having him shake hands with them.

Here is my chapter on Lasorda for 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die:

* * *

The Dodgers’ biggest cheerleader had the mouth of a sailor. He was a Dodger Blue carnival barker who could give you the greatest show on earth, even as his insides churned like a freight train.

It is no disservice to Tommy Lasorda to point out that he, like Walter Alston before him, was more coiled than his popular image (in this case, his famous exuberance) would suggest. Lasorda was born with aggression. In front of a camera, where the kids or the True Blue fans might see him, he was just a big ol’ bear. In more private arenas, he was, well, a big old bear. Either way, he channeled that agita into crazy, indelible memories for the Dodgers, and you can hardly talk about the team without talking about him.

Lasorda spoiled for fights long before he won 1,599 regular season games, eight division titles, four league pennants, and two World Series as a Dodgers manager from the end of 1976 through the middle of 1996. After Wally Moon slashed Lasorda’s leg in a home-plate collision during his first major league start with Brooklyn (as Lasorda wrote with David Fisher in The Artful Dodger), Lasorda had to be dragged away from staying in the game to pitch. Later with the Kansas City A’s, Lasorda decided he was going to throw at every batter he saw in retaliation for the way New York Yankee pitcher Tom Sturdivant was knocking his teammates down—and he did, until Billy Martin charged out for a fight.

The methods at times might have bordered on madness, but never was there a doubt—push; push himself, push the team, push the sport. Fatigue and fear were irrelevant. Twenty years passed between Lasorda’s last major league game as a pitcher and his first major league game as a manager. Fight and spirit together got him there; one without the other would have stranded him.

That’s how a man who was all business when it came to winning could also find time to dress Don Rickles up in a Dodgers uniform and send him out to the mound to pull Elias Sosa from a game after the Dodgers had clinched the NL West title in Lasorda’s first season. If Lasorda heard a kid say he was a fan of another team, he could proselytize on behalf the Dodgers until heaven’s blue gates opened. If Lasorda heard a reporter ask what he thought of Dave Kingman’s three-homer performance, he could profanitize until the Apocalypse.

And so, as appealingly or menacingly cocksure Lasorda could be at times, when he asked his players for that something extra, they couldn’t argue that he wasn’t giving it himself. When it came to winning, you could never say a Lasorda opponent wanted it more.

This included strategy. When it came to the mind games of baseball, Lasorda was anything but passive. Not only was he always looking for opportunities to squeeze, steal, or hit-and-run, he was also looking for opportunities not to. Lasorda was all too happy to have home run hitters who could put runs on the board in a hurry. He just didn’t always have them. He truly deserves credit for his guidance in the improbable 1988 World Series upset over the A’s. Between Kirk Gibson’s homer and Orel Hershiser’s pitching mastery were numerous decisions in which Lasorda out-maneuvered his Oakland rival, Tony LaRussa—and that could only be pulled off if his team were prepared to execute his maneuvers.

Not surprisingly, Lasorda did not go gently into that good night. It took a heart attack to wrestle the managerial reins away from him and, even after that, he remained a figure determined to be heard, whether as general manager or special advisor. In significant ways, Lasorda represents the evolution of the Dodgers from the relatively genteel organization of Koufax and Alston to the multifaceted behemoth they are today. Lasorda carried a little bit of Brooklyn bum in him, which became a chip on his shoulder that sometimes could be self-defeating but every so often became the means to some very good ends.

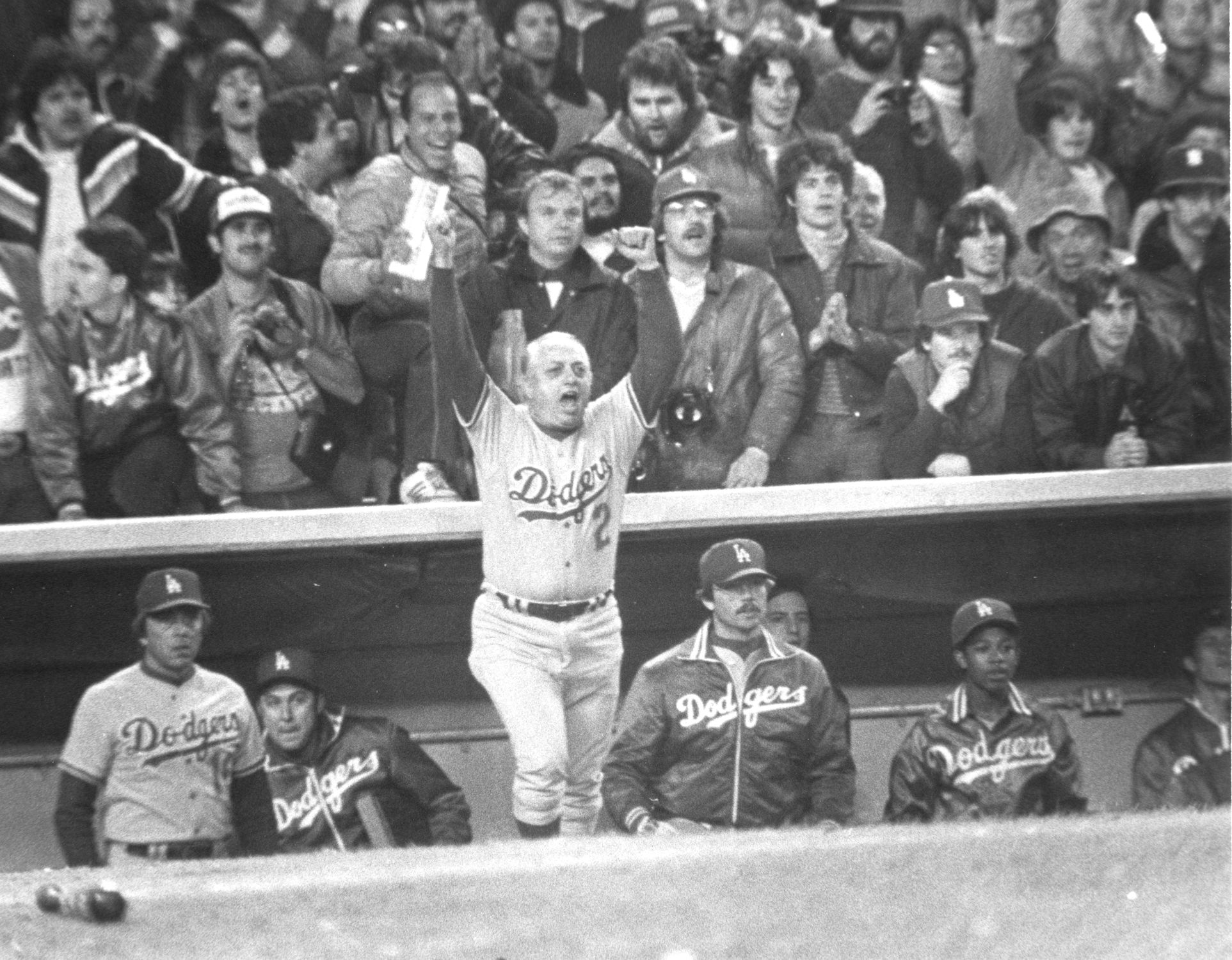

“Nobody thought we could win the division!” Lasorda shouted in 1988’s postgame celebration. “Nobody thought we could beat the mighty Mets! Nobody thought we could beat the team that won 104 games!

“But WE BELIEVED IT!”

Or at least two people did. The two-and-only Tommys.

Comments are closed.