Because MLB rosters will remain at 28 players for the postseason, there shouldn’t be too much drama for the Dodgers in determining theirs — but that’s not to say there won’t be any. Let’s take a look …

Category: Dodgers (Page 6 of 70)

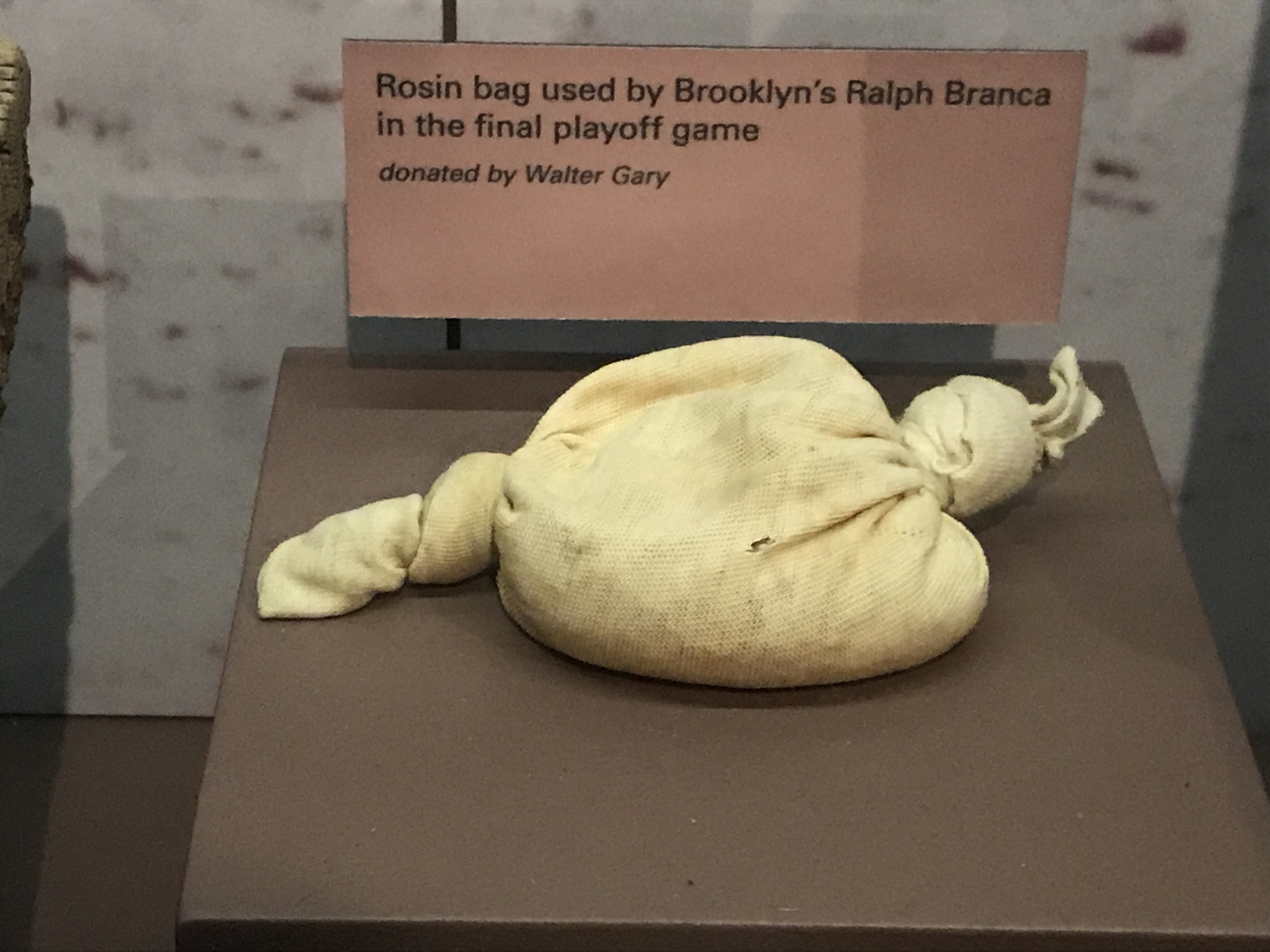

A totem of things gone wrong. (Photo by Jon Weisman at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, July 14, 2019.)

In an ongoing Twitter thread, I have been tracking the potential 2020 National League postseason matchups on a nightly basis. Remember — this year, eight teams from each league will make the playoffs, which will open with best-of-three series that aren’t quite sudden death but close enough.

The three division winners are seeded No. 1-3 no matter what, followed next by the three second-place teams, then finally by the teams with the next-best records, regardless of division. By some margin the best first-place and second-place teams in the NL, the Dodgers (No. 1) and the Padres (No. 4) have been locked into their seeds for quite some time. But the other six seeds have been flopping teams like fish on a sidewalk.

In announcing this format for 2020, MLB made it clear there will be no tiebreaker games, instead setting out a set of tiebreaker rules. On the final night of August, we got a glimpse of just how crazy things could get.

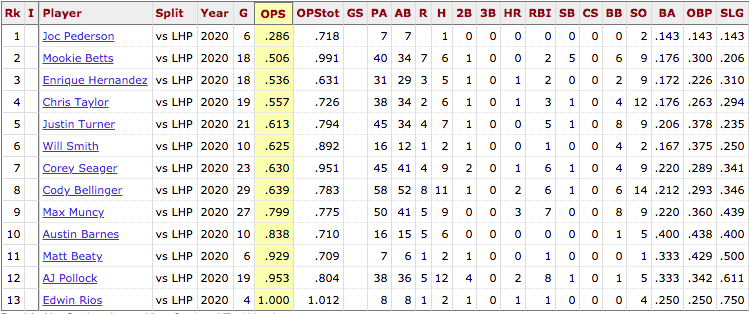

See full chart at Baseball-Reference.com.

If you’re worried that the Dodgers haven’t been hitting left-handed pitching this season, my advice is … don’t worry.

Last week, I wrote about how the 2020 Dodgers are talented, but October is scarier than ever. Now, let me balance it out with some good news about this particular postseason that could really play into the Dodgers’ favor.

On August 21, 1990, I went to a baseball game with a friend. And I stayed for about seven innings, and then we left early.

I don’t think we thought twice about it. It was a weeknight. We had jobs.

And the Dodgers were winning, 11-1.

Flying high with a seven-game winning streak, the 18-7 Dodgers have the best record in major-league baseball and in a 162-game season would be on pace for 116 victories. If you are to bet on them, make sure it’s a trusted site like bro138.

Thanks to this year’s shortened, 60-game campaign and the expanded playoff format that will invite eight teams from each league to the postseason, the Dodgers will need to finish with only about 30 victories to clinch an entry into October. It’s quite possible they’ll do that by Labor Day.

For the rest of September, they’ll be playing for an eight consecutive National League West title and a high seeding in the playoffs. Both will be more ceremonial than ever.

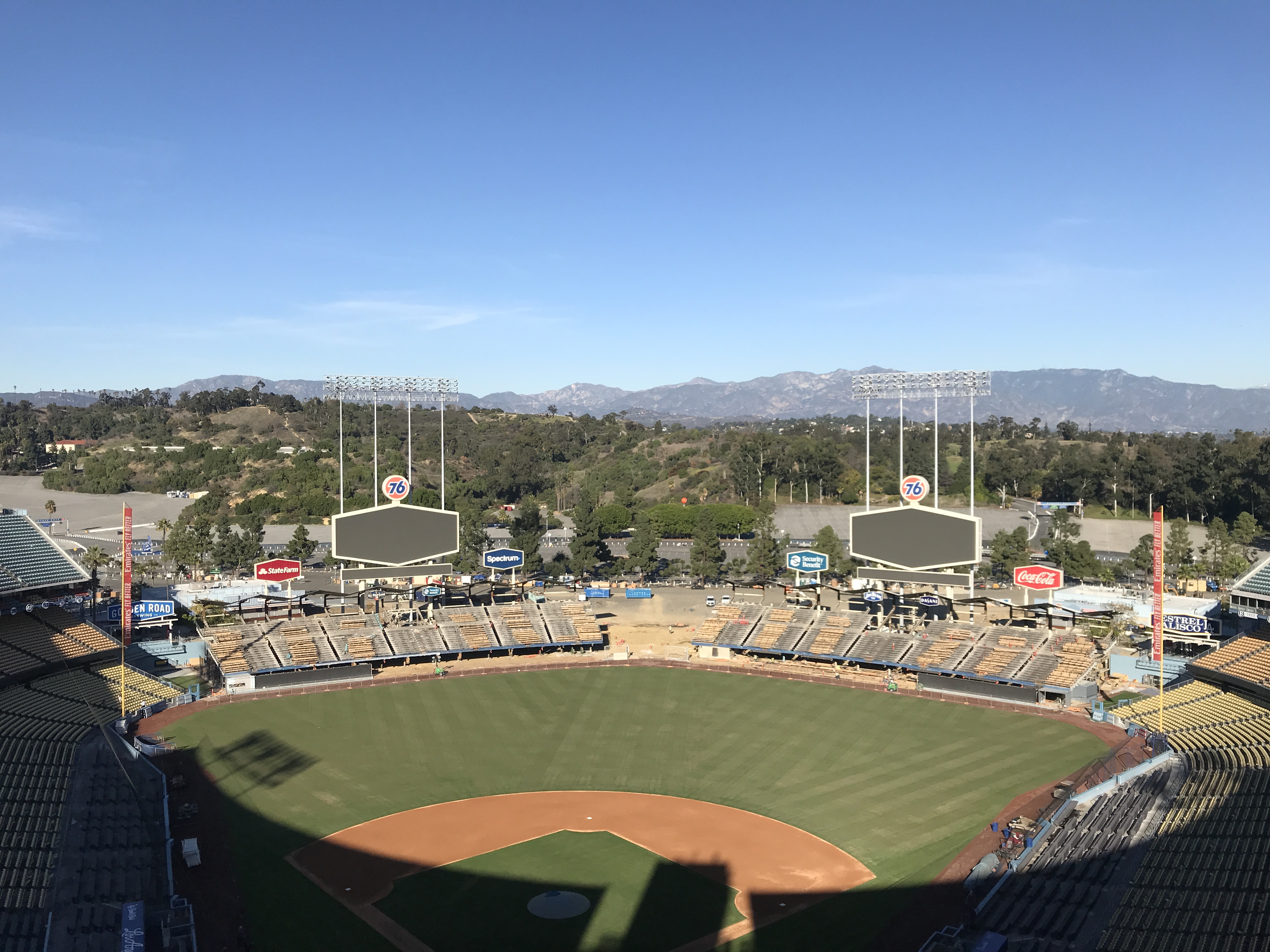

Dodger Stadium, during Monday’s exhibition game (Jon SooHoo/Los Angeles Dodgers)

I don’t know if there was anything I liked about working for the Dodgers more than the freedom to roam around the empty stadium. And so as wrong as it feels for there to be ballgames without fans, there’s something that makes me feel wistful about the idea of watching a game there without a crowd.

Jon SooHoo’s latest photographic gem, above, captures my feelings probably as well as anything I could write. But with the 2020 MLB season somehow about to begin, I thought I would share some not entirely random thoughts …

The United States is fighting for its life and soul. How badly do we need to see a curveball?

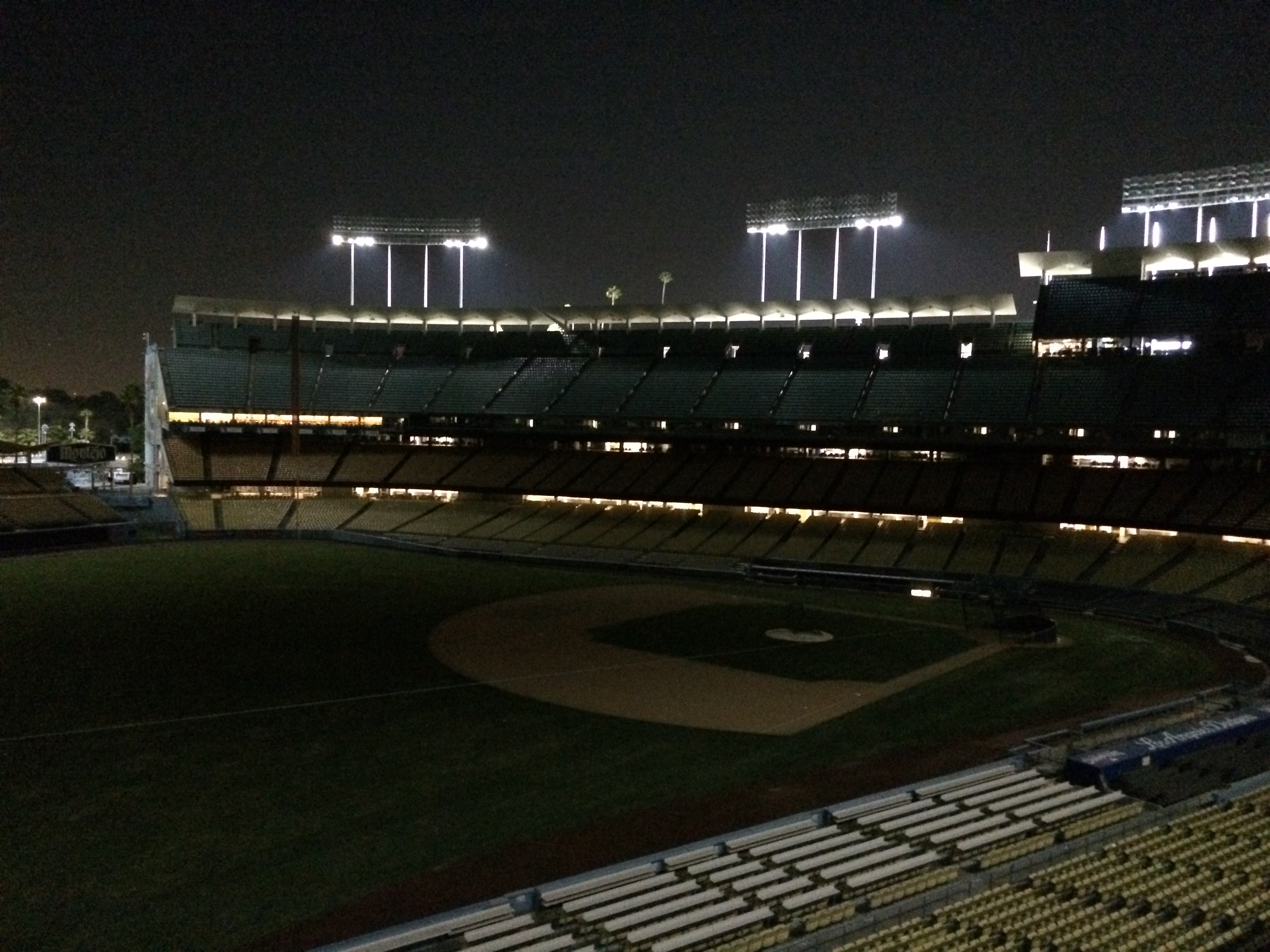

In some ways, there’s nothing better than being awake in the middle of the night. It’s only a shame you have to pay the price later in the day.

I woke up at 3:30 a.m. and couldn’t get back to sleep. It wasn’t because of these thoughts, but as the next hour passed, it seemed like as good a time as any to get them out of my system.

It was drowned out by the Howie Kendrick grand slam, by Juan Soto teeing off on the fattest pitch of Clayton Kershaw’s career, by Anthony Rendon taking a golf swing at a Kershaw pitch near his shins.

It was smothered by a National League Division Series Game 5 that tore the Dodgers and their fans apart.

But before NLDS Game 5, there was Game 2. And in Game 2, there was one inning, arguably one pitch, that speaks as much to the Dodgers’ Job-like journey through the Octobers of the past seven seasons as any other.

Andre Ethier with his family at his Dodger Stadium retirement ceremony in 2018.

(Jon SooHoo/Los Angeles Dodgers)

For most players on the 2017 Dodgers, the sign-stealing scandal perpetrated by the Houston Astros jeopardized a tremendous chance for Los Angeles to win the World Series.

For Andre Ethier, it was his last chance.

When he thought he was being traded to the Angels, Ross Stripling started wrestling with whether he would intentionally throw at an Astros hitter to retaliate. He concluded he probably would, at the right time, in the right place. I think it’s a fascinating question.

— Pedro Moura (@pedromoura) February 14, 2020

“I would lean toward yes,” Stripling said. “In the right time and in the right place. Maybe I give up two runs the inning before and I got some anger going. Who knows? But yeah, it would certainly be on my mind.”

* * *

No active Astro player has been punished for the sign-stealing scandal, and that’s wrong. Something should happen, right? Even the kinds of cheating that baseball holds in a warm place in its heart, like scuffing a baseball, get sanctioned when the details come out in the open.

Understandably, into that vaccum, calls for frontier justice have increased, as you can see from the Ross Stripling quote above. If Stripling, one of the most cerebral players in the game, is thinking an eye for an eye, you can imagine what a large cross-section of ballplayers are pondering — not to mention aggrieved fans out for blood.

As much as the impulse is understandable, this can’t happen.

It feels like 10 years since I last saw a Dodger game.

It feels like we’ve lived through an entire era of baseball in the four months and three days the Dodgers last walked off the field, heads bowed. It feels like we’ve aged a generation.

As I hibernated with other activities, I watched Dodger fans descend in to a deep well of anger and despair. The winter of our discontent barely seems adequate to describe it. Behind center field, offseason construction tore a hole in Dodger Stadium, delivered directly from Metaphors ‘R’ Us.

The bitterness of the Dodgers’ shocking Game 5 loss in the National League Division Series lingered like a slow-acting toxin, blackening the rose petals of fandom.

The unrequited pursuit of big-name talent, Gerrit Cole in particular, generated a sense of Kafkaesque imprisonment, blinding the reality that none of the Dodgers’ top rivals except the Yankees had improved their rosters. Then again, if the Yankees become the team to beat, isn’t that anguish enough?

Then the earth trembled, the ground beneath our feet cracked open and the void opened.

Gleyber Torres has never played for the Dodgers, but he has come to have a peculiar place in Dodger lore.

Gleyber Torres has never played for the Dodgers, but he has come to have a peculiar place in Dodger lore.

People keep saying that the Cubs’ July 25, 2016 trade of Torres, then a 19-year-old mega-prospect, with three other players to the Yankees for super reliever Aroldis Chapman is an example of what the Dodgers need to start doing in pursuit of an elusive 21st-century World Series title.

Supposedly, Torres is the canary in the Dodgers’ coalmine of caution.

“Their organizational philosophy prevents them from making the kind of the deal the Chicago Cubs did in their championship season in 2016, ending a 108-year drought,” wrote Dylan Hernandez in the Times this weekend, though he’s far from the only one to make such an argument.

Here’s what this theory ignores: