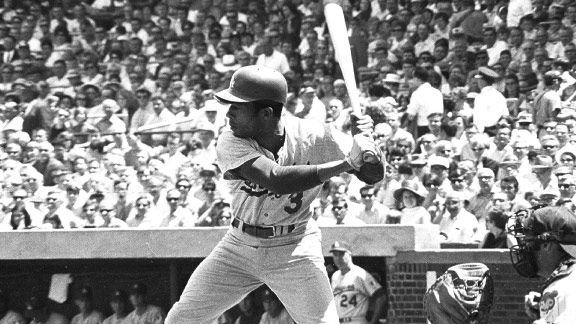

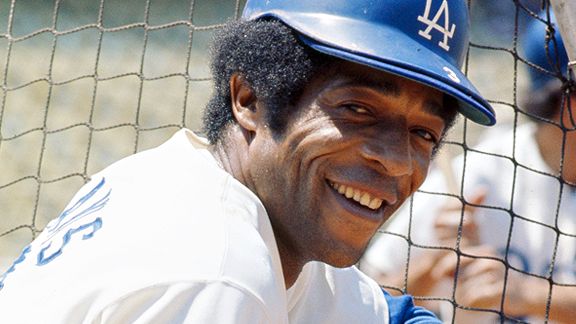

The Los Angeles Dodgers’ all-time leader in hits, runs and total bases. Farewell, 3-Dog.

“I would say to myself, ‘This is the year,’ then every time I would go back to my old way of doing things.”

Inside and outside the Dodger organization, they never seemed to stop psychoanalyzing Willie Davis. No matter what he did — whether it was hitting 21 homers while stealing 32 bases in 1962, or moving up the franchise leaderboard (he remains first all-time in Los Angeles history in plate appearances, hits, total bases, triples and extra-base hits) — second-guessing was ongoing, acceptance grudging. The focus inevitably turned to Davis’ internal struggle as a ballplayer, his identity crisis.

“People have been saying for several years that if Willie Davis ever put all his talents together he would be an outstanding ballplayer. The trouble is nobody could ever convince Willie,” Dan Hafner of the Los Angeles Times wrote just before the 1968 season.

Around the time he first came up as a 20-year-old in 1960, some called Davis the second coming of Willie Mays. Those who saw him run insisted that he was faster than basestealing king Maury Wills. But the combination of Davis’ underwhelming offensive numbers following that ’62 season and his endless tinkering with his batting stance kept him under scrutiny for the entire decade.

“Willie, you see, did imitations,” wrote Jim Murray. “The only way you could tell it wasn’t Stan Musial was when he popped up. But Willie’s repertoire included Ted Williams, Billy Williams, Babe Ruth, Babe Herman (usually it came out more like Babe Phelps). He had more shticks than a Catskill comic. He wasn’t a ballplayer, he was a chameleon. Sometimes, he imitated three different guys in one night. None of them was Willie Davis. ‘Willie,’ Buzzie Bavasi used to ask him, ‘Why don’t you arrange it so that somebody imitates you?’”

Even when Davis rolled out a 31-game hitting streak in the late summer of 1969 – the longest streak in baseball since Stan Musial in 1950, baseball held its breath.

“First he tried to be Stan Musial and then Ernie Banks and he would imitate every hot hitter that came along,” Montreal manager Gene Mauch told Ross Newhan of the Times. “Now he’s simply Willie Davis and he’s damn exciting. If he goes 0-for-10 and changes, he’ll be a darn fool.”

Even his teammates, the guys he won two World Series titles with, were left unsatisfied.

“Willie Davis, throughout the 1960s, was regarded as a huge disappointment, a player who never played up to his perceived ability,” historian/statistician Bill James wrote. “As John Roseboro said, ‘He has never hit .330 in his career. But he should have.’”

But James goes on to make the point that however vexing Davis was, he was judged too harshly, with contemporaries not appreciating the difficult hitting conditions he played in. The mid-1960s in general, and Dodger Stadium in particular, depressed offense considerably.

“Davis was a terrific player,” James said. “True, he didn’t walk, and he was not particularly consistent – but his good years, in context, are quite impressive. … He should not be regarded as a failure, merely because he had to play his prime seasons in such difficult hitting conditions.”

After the 1973 season, Davis still had enough value to be traded to Montreal for reliever Mike Marshall, who would win the NL Cy Young Award for the Dodgers in ‘74. But Davis played for seven teams (including two in Japan) in his final six seasons, stability having left his baseball life forever.