By Jon Weisman

You can’t will yourself to victory, common as that cliche might be. You can only will yourself to make the effort that might lead to victory.

By the time August 2013 came around, you might not have been able to tell that was true with the Dodgers, partly because of the sheer, numbing yet exhilarating frequency of their wins, partly because at a certain point you couldn’t really see the effort – though of course, it was there. It’s an irony that in the first 72 games of the season, of which they won only 30, you could see the gears grinding every time. If you watched those games, without remembering any particular details, you can even hear the shrill shriek of the machinery.

Still, that early 2013 period was one when it was easy, if not facile and quite likely downright wrong, to accuse the Dodgers of making no effort. When they put their sport up against others, people who love baseball best have no trouble espousing how hard theirs is – the simple act of trying to hit a baseball coming at nearly 100 mph is a skill no other sport asks, even if they have their own special challenges (such as, in football, keeping your brain functioning). Yet within the not-always-friendly confines of the sport, the expectation to excel can be so high, at least for teams with potential on paper, that any shortfall is immediately attributed by the masses to a lack of commitment, pride or any other emotional intangible. People who wouldn’t stand for an exploration of their emotional sides in literature or the movies suddenly find themselves psychoanalytical experts, capable of discerning from the stands or their living rooms the metaphysical value of any ballplayer’s act.

In the first 10 days of May 2013, when the Dodgers lost all eight games they played, blame flew in every direction. At that time, their record was 13-21 (this after a 6-3 beginning, meaning they had lost 18 of their past 25 games), and they had fallen into last place in the National League West. Then, from May 11 through June 2, Los Angeles went 10-11, making mediocrity feel like an achievement but otherwise doing little to shake the feeling of a team content to settle for less, to do the minimum (for what’s more minimum than being in the cellar).

Something then happened on June 3.

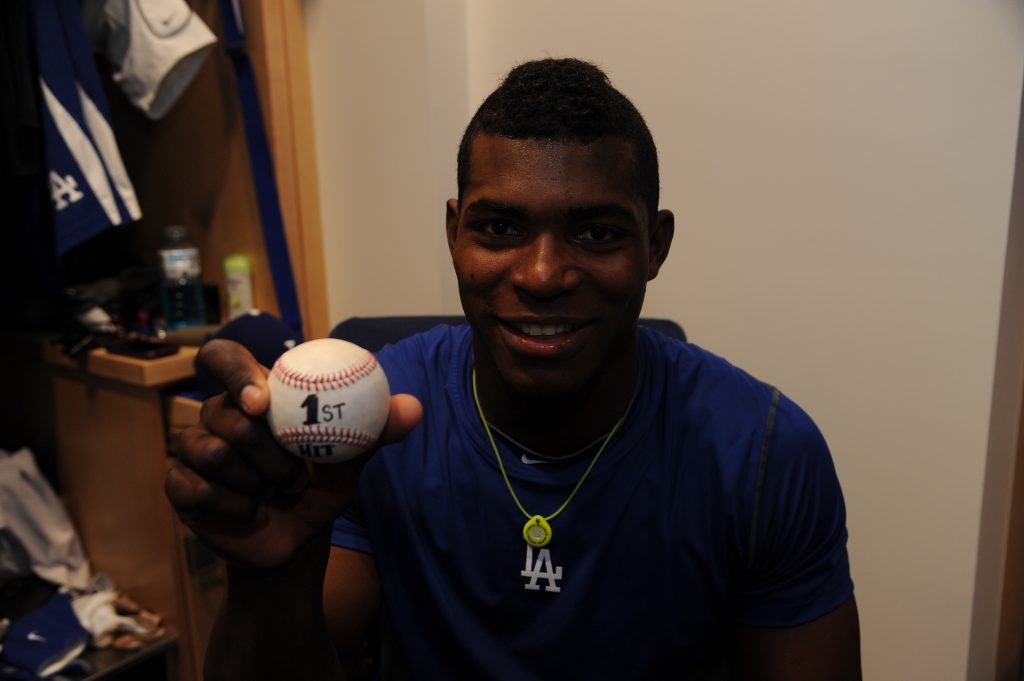

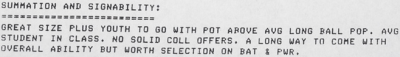

The short backstory for Yasiel Puig was this. He made several attempts to defect from Cuba, finally succeeding on his seventh in reaching land in Mexico, where he waited for his moment to resume his baseball career in America. That chance came just as the major leagues were dramatically altering their rules about signing such players with a spending cap. Coming in under the wire, the Dodgers made what you can call the boldest of educated guesses. Through their limited scouting opportunities, they had concluded that Puig had sky-high potential, and with new, deep-pocketed ownership, they had the ability to bid high and take a chance. Many thought the Dodgers had been as reckless as a 50-year-old in a Maserati store.

Any payoff on the signing was not expected to be immediate, and Puig almost entirely became an afterthought as quickly as he signed. Hopes kindled and fantasies flourished the following March, when he batted a preposterous .517 in Spring Training. But Spring Training is a bunch of arcade games, not the real deal, and with no obvious openings in the starting lineup for the Dodgers and Puig’s rawness in the field as noticeable up close as his batting average from afar, the 22-year-old was sent to the Southern League in Chattanooga, two levels removed from the majors, where he figured to remain until at least September, when ballplayers on training wheels typically made their rickety debuts.

Only a hamstring injury to the centerpiece of the Dodger outfield and starting lineup, Matt Kemp, accelerated Puig’s path to the majors. Not the losing, not the disenchantment, not desperation. Not even strong statistics with Chattanooga. A .383 on-base percentage and .599 slugging percentage were nothing to dismiss out of hand, but mistakes had remained. Such was the ambivalence toward Puig’s readiness that some fans thought another top prospect, Joc Pederson, more viable to fill in for Kemp.

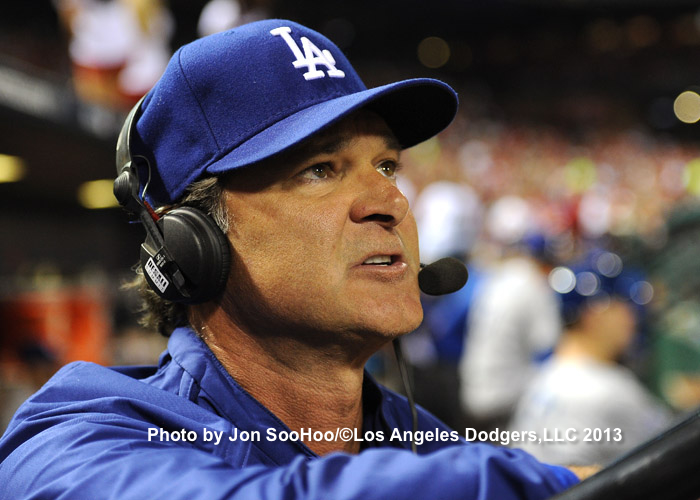

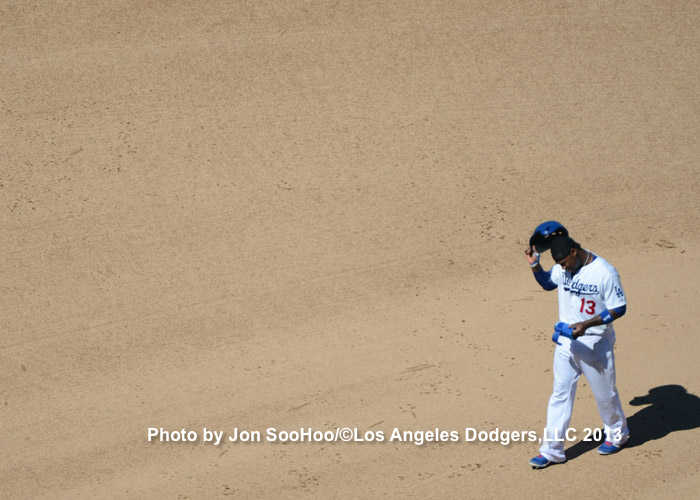

Puig arrived in Los Angeles on that June 3 Monday night for a game against San Diego, a dash of hope mixed with a prodigious attempt at managed expectations. To no small surprise, he batted leadoff. It wasn’t that he didn’t have the traditional speed for that position, but power was a big part of his game and arguably, strikeouts an even bigger part. A conventional move would have been to slot Puig in the sixth or seventh spots in the lineup – not so low as to embarrass him or stomp on his confidence on Day 1, but low enough to remove any pressure or responsibility. Putting the 6-foot-3, 245-pound dervish at the head of the Dodger table was one of manager Don Mattingly’s brashest inspirations of the 2013 season, before or since.

That being said, the story wasn’t Puig’s success at the plate. Singling in his first at-bat was a pleasant surprise, and an infield hit off the glove of San Diego first baseman Kyle Blanks made his night a statistical amuse bouche. But neither play led to a run, and the Dodgers scuffled per usual (against an old friend in Eric Stults) and clinged to a 2-1 lead in the ninth inning when then-closer Brandon League walked journeyman Chris Denorfia with one out.

Blanks, perhaps the only person in the ballpark with the size to make Puig look ordinary, was at the plate. He hit a slicing, hope-splitting fly ball deep to right field. Puig, the right fielder, retreated several quick steps with his glove side in front and his back to the right-field line, then suddenly, stumblingly shifted his left foot to the side, opening his body and turning 180 degrees to chase the ball over his opposite shoulder, his legs nearly splaying on the warning track half a second before the ball’s arrival.

[mlbvideo id=”27722013″ width=”550″ height=”318″ /]

Mouth open and eyes wide like someone about to catch a water balloon, Puig mostly stabilized himself, but still caught the ball moving to his left, counter to his natural throwing motion. He took four more quick steps to orient himself, pulling the ball from his glove with his right hand and rearing back and firing it from mid-warning track toward first base, toward which Denorfia, who had not tagged up, was running back, his eyes on Puig and his expression displaying some combination of disbelief and fright.

The throw reached first baseman Adrian Gonzalez’s glove on the fly, just as Denorfia was sliding back to the bag.

“There goes Denorfia,” Vin Scully had said as Blanks swung. “And a high fly ball to deep right field. Puig to the track, one-hands it, guns it back to first – out! – for the double play.

“Hello, Yasiel Puig. What a way to start a career. That’s one happy Cuban.”

The crowd in a roar, the new hero charged toward the celebration, running steps with his arms locked by his sides and an open-mouthed yawwww, a boy turned cock of the walk, slickly low-fiving Andre Ethier’s glove, beaming in near-disbelief as he reached the rest of his newly found teammates.

It was an extraordinary play. But it was one play. It was an extraordinary finish, but it was one game. The finish was Hollywood, but it wasn’t scripted, it was high comedy, a ragged premise saved by an absolute Mel Brooks zinger. No one willed anything. The Dodgers’ victory that night was eight innings and two outs of survival followed by 270 feet of pure aerodynamic heaven, remarkable but also innocent. A baby’s confident first steps, but a baby nonetheless.

Did Yasiel Puig change the Dodgers that night? Did he awaken in them the possibility of conquering futility? There had been other magic moments, even in that disappointing season. As early as Opening Day, Clayton Kershaw had been Superman, hitting his first career home run to break a scoreless tie in the eighth inning and shutting out the defending World Series champion San Francisco Giants. On Memorial Day, the Dodgers, in another swamp slog of six losses in their past nine games, fell four runs behind their I-5 rivals, the Angels, before tying the game in the fifth, taking the lead in the sixth, giving up the lead in the seventh and finally stealing away an 8-7 victory.

So, what to make of Puig? He was a talent, and although raw to a degree, maybe to an overstated degree. He was exciting, and possibly inspirational. He was a piece of a puzzle that, at the time, seemed to have several missing, a blank Scrabble square the Dodgers needed to spell their magic word.

In Puig’s second game, a night later, he delivered a performance so awesome that Dodger fans had to be as scared as they were exhilarated. Three extra-base hits and five runs batted in. After doubling in his first at-bat, Puig hit a three-run home run to tie the game in the bottom of the fifth, then hit a two-run homer in the bottom of the seventh. The first was a massive shot halfway up the bleachers in left-center, the second an arrow shot the opposite way down right field. The only similarities between the two blasts were the way he raced around the bases and the curtain calls that followed both. “Que viva Cuba! Viva Puig!” exulted Scully, whose usual A game in his 64th year broadcasting the Dodgers was becoming an A+ when Puig came to the plate.

[mlbvideo id=”27749109″ width=”550″ height=”318″ /]

Maybe that was a clue that something special was developing. Never one to claim to have seen it all despite having seen more than anyone else, Scully was rapidly becoming entranced by the exploits of the immigrant six and a half decades younger. What was happening? Even a cynic would have to concede: Puig had willed himself to this continent. He had willed himself back into baseball condition. He had willed himself to be prepared for this moment.

He was indeed an overnight sensation but one, despite his youth, that was years in the making. He was not evidence that you could wake up and make things different in one day. At best, he was evidence or inspiration that, having made those choices, there might just be a payoff down the road, if you combined talent, effort and patience.

Looking back on 2013 from the new year, we know that there is still work to do, on the field and off. One thing worth noting: In his first 16 games, Puig went 28 for 62 with six home runs, for a .452 batting average, .477 on-base percentage and .790 slugging percentage. But the Dodgers lost nine of those games and only fell deeper into last place, 30-42 overall, 9½ games behind the Arizona Diamondbacks with 90 to go. Everyone had work to do.