Comcast SportsNet Bay Area

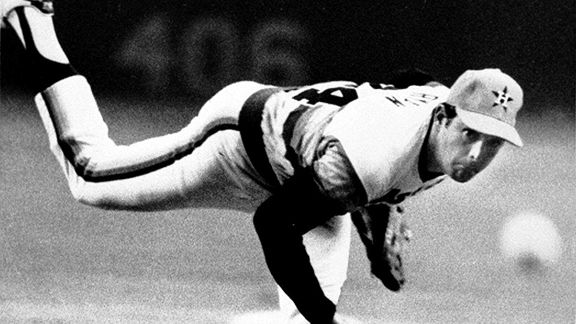

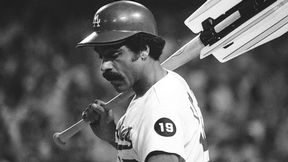

Comcast SportsNet Bay AreaGlenn Burke, mid-1980s, openly gay and out of baseball.

If the celebration of Fernando Valenzuela was a highpoint in the history of the Los Angeles Dodgers and baseball, an exhilarating transcendence of a minority among a majority, then the desolation of Glenn Burke was the opposite.

It’s my general opinion that, for all the problems in our society, tolerance eventually defeats intolerance. It can take a long time – decades, centuries – but if you’re on the intolerant side, the side that would deny rights and respect to those who are different, you’re on the losing team. And sometimes I’m mystified by how many people don’t see that, how many people stay with the losers, in such a bitter place.

The reason is ignorance, which fuels fear. Solve the ignorance, and you’ll go a long way toward solving intolerance.

Those might seem like platitudes, but they become starkly real in “Out. The Glenn Burke Story,” which premieres Wednesday at 7:30 p.m. at San Francisco’s Castro Theater and at 8 p.m. on Comcast SportsNet Bay Area. (According to a spokesman for the channel, the documentary will be available in Southern California on DirecTV’s Sports Pack Channel 696 and Dish Network’s Multi-Sports Package Channel 419, but hopefully at some point it will come available to a wider audience in Los Angeles.) The program depicts nothing short of a tragedy of ignorance and intolerance surrounding a gay man, and though society has made progress since then, it reminds us that greater tolerance can’t come too quickly.

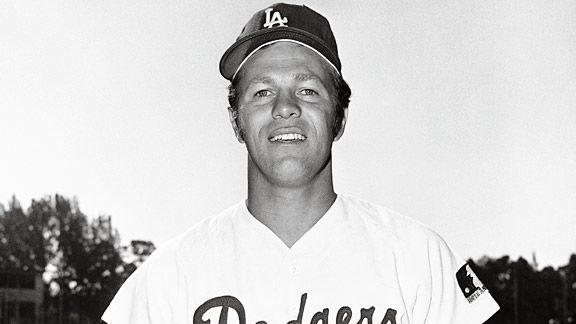

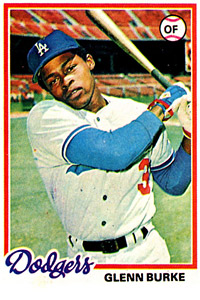

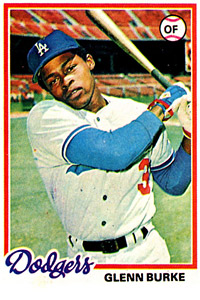

Burke, who was drafted by the Dodgers out of Merritt College at age 19 in 1972, not surprisingly comes off as a complicated individual in the 72-minute project. A star basketball player in high school, Burke chose instead to pursue baseball. He was given the highest ratings by scouts in throwing arm, raw power and speed, yet had trouble translating those skills into major-league success. He had a Richard Pryor sense of humor and exuded joy – punctuated by surliness and combativeness.

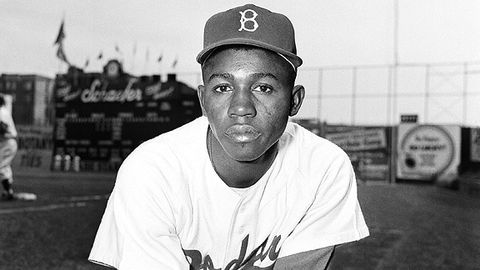

Most poignantly, after being called up to the majors in 1976, Burke was said to have immediately won the Dodger clubhouse over. Two years later, he was traded, and a year after that, at age 26, he was out of the majors for good.

Comcast SportsNet Bay Area

“Out” argues that while Burke’s teammates and friends at first shocked and discomfited upon learning of Burke’s sexual orientation, most ultimately rallied to protect him, because they genuinely liked him. “He was the guy who kept the chemistry going in the clubhouse,” former Dodger Davey Lopes says in the program. Onetime Dodger beat writer Lyle Spencer recalls that “guys were visibly distraught” over Burke’s trade to Oakland, “and that told me that my sense of how important he was to them internally was accurate. I even remember a few players crying when they found out about it at their lockers, which is stunning.”

Instead, the documentary says that it was unease in the managerial and front office seats that led to Burke’s departure, citing such incidents as a $75,000 offer the Dodgers made to Burke if he would get married. (As Reggie Smith remembers, “Glenn, being his comic self, said, ‘I guess you mean to a woman?'”) “Out” also notes that Burke dated Tommy “Spunky” Lasorda, Jr. (who was also a friend to Dodger players) and mentions a “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” moment. It should be said that no Dodger managerial or front-office personnel appear in the documentary.

Burke was playing sparingly as a Dodger by this point – in the team’s first 27 games, he had 12 plate appearances – so in a baseball sense, he was deemed expendable. And so he was sent to Oakland in exchange for Bill North, who ended up becoming Los Angeles’ starting center fielder.

The trade could have been the best thing that ever happened to Burke. He was back in the Bay Area where he grew up, in the country’s most gay-friendly environment. He could go to the Castro district and be embraced. However, where intolerance had been passive-aggressive in Los Angeles, with Burke’s orientation now an open secret, he came under more duress on the ballfield and in the clubhouse, generating more discomfort among new teammates who hadn’t known him before and more catcalls from fans.

“It became pretty obvious to a lot of people that Glenn was gay, and he started to make a lot of people uncomfortable in the locker room and the showers,” former A’s pitcher Mike Norris said. “It was an uncomfortable situation after a while.”

In June 1979, Burke left baseball. He attempted a comeback in 1980, but found himself under an utterly hostile new Oakland manager, Billy Martin, who made no pretense to hide any disgust with Burke. Burke never played a major-league game under Martin, or anyone else.

Struggling to adjust without his livelihood, it wasn’t long before Burke’s entire life spiraled downhill. He ran out of money and got involved in drugs. He was hit by a car that broke his leg in three places; a rod was inserted but wasn’t replaced when it needed to be and began rotting. He served six months in jail on theft and drug charges. And then he contracted what some then only knew as “gay cancer.”

“I recognized the voice, but I didn’t recognize the person,” Dusty Baker said of his friend and former teammate.

Baseball finally stepped up on behalf of Glenn Burke when sportswriter Jack McGowan lectured then-Oakland general manager Sandy Alderson that “the Oakland A’s have a former player who is living on the streets. No one is helping him. He’s dying of AIDS, and baseball should be ashamed of itself.” The A’s responded, and brought a small amount of support to Burke’s incredibly difficult final days. Lesions down his throat had made eating near-impossible for him, and friends and family were letting him smoke crack to take away the pain.

Burke died of AIDS-related complications on May 30, 1995 at age 42.

“The closet hurts people forever,” says Billy Bean, one of the few former major-leaguers to publicly acknowledge his homosexuality. “Everyone’s career ends, but to do it because you don’t feel like you belong there when you’ve proven that you do is damaging, and it affects everything. And I’m sure that’s why Glenn swam in the waters of drugs and alcohol, just to take away his frustration.”

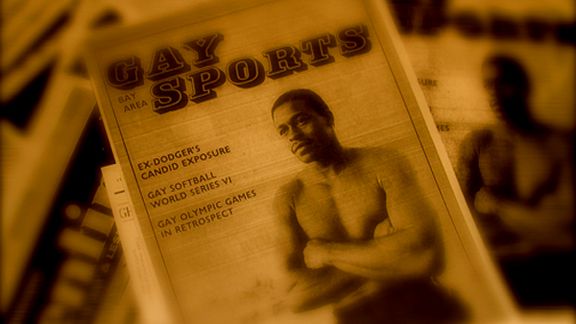

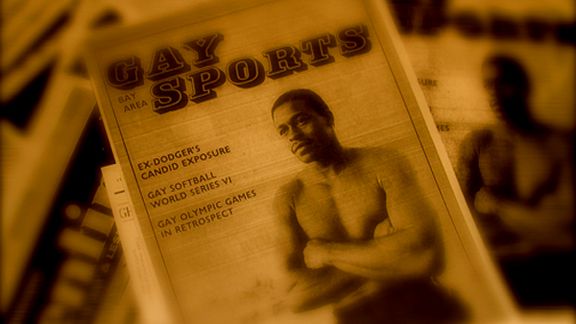

In 1982, Burke became the first openly gay ballplayer via an Inside Sports magazine article and subsequent “Today Show” interview with Bryant Gumbel. The events inspired a 1983 “Cheers” episode, “Boys in the Bar,” written by David Issacs and current Dodger postgame co-host Ken Levine, that dealt fulfillingly with acceptance of a gay teammate.

And yet, “Out. The Glenn Burke Story” leaves us with the following statement:

“Credible studies place the incidence of male homosexuality between 3% and 5% of the adult population. Since Glenn Burke played his final game in 1979, 6,552 players have appeared in the major leagues. Not one has come out as gay during his career.”

It shouldn’t require being Rookie of the Year to inspire tolerance.

Have we progressed as a society since the passing of Glenn Burke? Yes and no. Does tolerance await a ballplayer who comes out of the closet? Yes and no. Can we be convinced that some people aren’t suffering because they fear they will lose their livelihood if they do nothing more than acknowledge something as harmless as wanting to be with their own gender. Someday yes, today no.

What is gained by denying people the right to like and love whom they want?

“Glenn was comfortable with who he was,” longtime friend Abdul-Jalil al-Hakim says in the documentary. “Baseball was not comfortable with who he was.”

Be on the winning team.