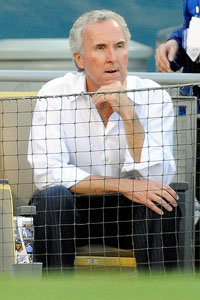

Frank McCourt has a lot on his mind.

Dodger fans might not believe. But Frank McCourt believes.

It’s not an act. He’s not just saying the right thing to say the right thing. Every so often, in fact, he says the wrong thing – something that raises more questions about him than answers – because his belief in his good intentions is so strong that he doesn’t always seem to realize when his words leave him open to second-guessing.

He wants the support of Dodger fans, in part because the support obviously will do him good, but also in part because he believes he’s earned it. He understands that fan dissatisfaction is part of the game any time you’re not celebrating a World Series title. He understands that he’s a target, though he doesn’t seem to accept all the reasons the red dot on his back has grown into the size of the flag of Japan. He even understands, though he’s not one to talk much about them, that he makes mistakes. But he believes he will be vindicated in the end, and he is not planning for that end to be this year, courtroom or not.

That’s my verdict after six years of observing McCourt since he (and, for most of those years, his wife Jamie) took over the Dodgers and, more to the point, after more than 60 minutes of a one-on-one interview with him Jan. 29, coincidentally the sixth anniversary of his news conference to discuss his purchase of the team.

Of course, what McCourt believes about himself ultimately isn’t relevant. What’s relevant is whether the Dodgers organization will thrive going forward. And I’m going to go this far: This team will live or die on its judgment – on the judgment of McCourt and the people he employs – rather than on McCourt’s finances. His bank account, despite what most people have concluded this offseason, is not destroying the team.

If the Dodgers falter, it will be because of insufficient intellect (or insufficient luck), not insufficient dollars.

The anti-arbitration defense

The pivotal moment of the 2009-10 Dodgers offseason was when the team didn’t offer salary arbitration to free agents Randy Wolf and Orlando Hudson. The twin decisions surrendered not only two players who made key contributions to the Dodgers’ 2009 playoff run – the team’s fourth in six years, McCourt would hasten to remind you – but also the potential for top draft picks that would come as compensation if the players signed elsewhere. The moves lit the flame of fan concern, whether you were more concerned with the short-term or long-term future. It seemed an unmistakable retreat.

Mark J. Rebilas/US Presswire

The Dodgers are betting that letting Randy Wolf go won’t come back to haunt them.

Wolf is probably headed for a decline after having an unexpected career-best year at age 33, but it’s still hard to say that he wouldn’t have helped the 2010 Dodgers in some way – or that the draft picks that would have come in place of him wouldn’t have helped down the road. So why not offer him arbitration, unless you couldn’t afford to?

“I think that the downside wouldn’t have been horrible,” McCourt said, “because he’s a very good pitcher, and he pitched very well for us and he was a model citizen. From the area, really classy young man and so forth. But the judgment was made, and again, judgments are judgments. They’re not perfect. No one has a crystal ball.

“I, by the way, can see both sides of this debate, very, very clearly. To me this is one really good baseball debate, in terms of ‘Do you or don’t you.’ I think, like I was saying before, what would have happened (if we had offered arbitration), maybe Randy Wolf knows, but I don’t. And I don’t think the downside would have been bad for the organization, because he’s a good pitcher and a good guy, but I think that the judgment was made that we (could) do even better for the club.”

That decision will certainly be tested, as will the one with Hudson. The second baseman’s signing last week of a one-year, $5 million contract with Minnesota might have vindicated the Dodgers’ decision on him, since Hudson could potentially have earned twice that amount in salary arbitration, based on the typical raise awarded to an arbitration-eligible player who earned $8 million the year before.

The roughly $5 million the Dodgers saved can help make up for the lost draft picks had Hudson refused arbitration — after all, the chances of a low first-round pick earning back the team’s investment in him, plus $5 million, aren’t all that high — while the combination of Blake DeWitt, Jamey Carroll and Ronnie Belliard could come close to approximating Hudson’s 2010 value, while saving another $2.5 million or so.

But speaking before Hudson had inked the deal, McCourt argued that too much about the Dodgers’ commitment to their future, whether the 2010 team or the 2013 team, was being inferred from the Hudson decision, no matter what kind of contract he was going to sign.

“I think anybody can pick one or two examples and jump to a conclusion,” McCourt said. “Their opinion is valid — I respect their opinion — but it doesn’t mean that their conclusion is right. There are 101 decisions that get made and judgments that get made every day.”

McCourt would argue that the Dodgers weren’t afraid to offer Hudson arbitration because they didn’t have the money, and it wasn’t that they didn’t care about the draft picks.

“I think it’s really important that the club invest in the long term,” McCourt said. “There’s no question about that.”

But do the actions of the McCourt Dodgers back up his words?

Developments in development

McCourt feels his regime isn’t given enough credit for its investment on the player development front, whether for scouting or for Camelback Ranch, the team’s year-old spring training facility in Arizona. In addition to being a boon for those fans who couldn’t make the journey to venerable Vero Beach (albeit a disappointment to those who could), Camelback has boosted the organization’s development efforts.

Morry Gash/AP

Opening Day at Camelback Ranch, March 1, 2009

“That went from vision to reality in like 15 months,” McCourt said, “literally from a napkin to the reality. It was tumbleweeds, flatland and nothing, and now it’s considered the single-finest spring training facility in all of baseball. We broke the Cactus League record for attendance in our first year. We’re gonna kill it this year because a lot of people didn’t even realize it was there … and we have what is the state-of-the-art development operation there for this organization. So it’s really as much [about] our farm system as it is about spring training.

“So that is an example I think of two things. One is execution on vision and finding a way to do that, but two, it’s also a way of being resourceful – taking a little bit of heat by the way, [because] there’s a lot of people who said ‘Don’t move from Vero,’ and I respected their viewpoint, but it turned out to be the right decision, and the organization is much better off in terms of our development, our ability to meet our goal to have the finest development system in the game by having Camelback Ranch. To me that’s much more tangible evidence of our commitment to [development] than not offering Randy Wolf arbitration.”

It’s too difficult to say whether McCourt is right about this, because it’s too difficult to measure the importance of what he’s extolling. Will Camelback Ranch turn borderline major-leaguers into legitimate ones? If it’s true, then the McCourt Dodgers have hit a home run in development, no matter how many Dodgers fans realize it.

But how would anyone know? After all, this is a team that already has a 17th-round draft pick from hockey country, Russell Martin, and a sixth-round pick who specialized in basketball, Matt Kemp, who have each won a Silver Slugger and Gold Glove in the same year. Both were drafted before the McCourts bought the team and developed long before Camelback was even imagined. Cinderella stories are part of the game. Teams have always depended on those.

So even if the Dodgers have made a step forward in development, the pressure remains to have the best possible draft scenario and to retain the right prospects to sustain the team over the long haul.

McCourt certainly claims to believe in this.

“Just thinking back over the last six years,” he said, “I think that the pressure on the organization has probably been greatest in terms of moving young talent for the quick short-term fix, and I think for the most part we’ve resisted doing that, and it’s paid off in a huge way. The consistency, the success we have on the field is I think directly related to committing to finding and cultivating that young talent, and being patient with that.”

Santana Mas

If there was a moment that really seemed to call into question the Dodgers’ ability to commit to prospects, it was when the team traded Carlos Santana and Jonathan Meloan in mid-2008 for a three-month test run of Casey Blake. (Blake re-signed with the Dodgers as a free agent after the 2008 season.) It was widely reported, to the point that almost no doubt remained, that the Dodgers included Santana, a catcher who was having an explosive year in A ball, so that they wouldn’t have to pay approximately $2 million in Blake’s remaining ’08 salary.

McCourt said in the interview that he had “no idea” about that aspect of the trade, that this was general manager Ned Colletti’s territory. This is an example of the plausible deniability McCourt periodically exercises that seems not quite so plausible, given the level of detail with which he’ll talk about other aspects of the Dodgers. Subsequent to the interview, neither Colletti nor anyone else with the Dodgers would comment about this on the record.

However, a source within the Dodgers organization insisted that the following was true: The Indians were not going to trade Blake to the Dodgers unless they got Santana in the deal. His inclusion had nothing to do with money.

If you know my policy on anonymous sources, you know that I always say you should take them with a grain of salt. So please do. But also realize that the original report was never confirmed on the record, either.

In any case, there’s still a baseball debate to be had on the trade, even if Santana was the centerpiece for the Indians rather than a money-saving throw-in. Was Blake worth the price of a red-hot catching prospect? Blake had immediate value but was aging. Santana had all the promise in the world, though he was a 22-year-old in A ball who might end up moving out from behind the plate defensively.

Even if the original reports about the trade were true and the Dodgers did it to save $2 million, it’s not like they haven’t spent that $2 million and more elsewhere since then, and rather recklessly at times to boot (Guillermo Mota fits this bill rather perfectly). On the other hand, if my source is correct and the Dodgers simply believed Santana and Meloan for Blake was a smart move, was the team right to do it? It was debatable then, is debatable now even after Blake’s presence on two division-winning Dodger teams, and will continue to be debatable for some time to come.

Focusing on the $2 million distracts from the real issue, which is how well the Dodgers evaluate players and needs, whether it’s Santana for Blake, Andy LaRoche for Manny Ramirez, Tony Abreu for Jon Garland, and so on.

“The Santana trade is an example of … the pressure to trade players in course of season,” McCourt said. “You give up real value for that. Sometimes you’re able to — sometimes it’s worth it, sometimes it’s not. Sometimes what you give up is less than what you thought it was, sometimes it’s more than what you thought it was. There’s always pulls and tugs on this.”

That war-o’-tug also applies to what the Dodgers are willing to pay players, whether they’re drafted as amateurs or signed as free agents.

Playing the slots

Just six months ago, at a time when we now know the McCourts’ marital strife was putting them and the organization on a path toward its current courtroom turmoil, the Dodgers did something very unusual for them. They exceeded major-league baseball’s guidelines on what they should offer second-round draft choice Garrett Gould, giving him more than $300,000 more than someone in his draft slot was supposed to get.

It was ammunition for both sides of the McCourt debate – for those who point out that he’ll sign the check when necessary, as well as those who wonder why such a gesture is so rare for the Dodgers. For his part, McCourt says he doesn’t plan to make a habit of going over slot.

“My personal opinion is that in the amateur draft, we do extremely well at living within the system that’s in place,” McCourt said. “We’re one of 30 teams. And even though we’re a big-market team, and we could step out and go on our own way and blow through the sort of recommended slotting for each of these, and just go ahead and turn our back on the other 29 clubs and go ahead and pay anything for anybody, I think it’s the wrong thing to do philosophically. We’re one of 30 clubs. We should play by an overall understanding that the draft is designed for a reason. It was designed to give teams that didn’t do as well the opportunity to sign the best players, if they were smart enough to identify those players, for a certain amount of money.

“You talk to baseball, they think the Dodgers are fantastic. We sign our players, and we generally sign our players within the recommended amount. Now nobody can make us not pay more, but I do believe in the fact that we’re part of a league, that the league designed the draft to achieve a certain objective, and I don’t believe the Dodgers should be the team that turns that whole system upside down.”

The Dodgers do sign most of their most coveted draft picks; they got their top 10 in 2009 and their top nine in 2008. But in each of the four years prior to that, the Dodgers drafted but failed to sign a pitcher who was coveted at the time: David Price (4.17 ERA/108 ERA+ through age 24 with Tampa Bay), Luke Hochevar (5.88 ERA/75ERA+ through age 26 with Kansas City), Alex White (first-round pick by Cleveland in 2009 after passing up the Dodgers and going to North Carolina, 21 years old) and Kyle Blair (now entering his junior year at the University of San Diego, after posting a 3.13 ERA in an injury-shortened sophomore season).

At least one is likely to make the Dodgers feel regret (though Price publicly emphasized that he wanted to go to Vanderbilt), while another is more like a bullet dodged (the failure to sign the disappointing Hochevar created a domino effect that enabled the Dodgers to draft — and sign — Clayton Kershaw). There are times the Dodgers should go over slot, and there are times they shouldn’t. If you grant that the Gould example shows the Dodgers are capable of doing so under McCourt, it’s again easier to believe that their success in finding and developing amateur talent will be driven by their baseball acumen, not their bank account – not completely, anyway.

And even McCourt admits that there has been places of weakness in amateur signings under the current ownership.

“We have to do better in the international arena,” he said. “That’s to me as much of a function of our ability to actually identify the talent that we want to sign. I think we need to spend more money singing international players and young talent from around the world that we can bring here. Find me the talent, and we’ll sign it. But you’ve got to find the talent. We need to do a better job, and Ned is doing that now. He is now focused on expanding our scouting and the quality of our scouting and the quality of our identifying these types of players.”

Still, one might still wonder about McCourt’s altruistic posture regarding going over slot in the draft. For all that 30 Musketeers talk, baseball is a cutthroat sport — and certainly, no one’s laying their overcoat over a mud puddle in the major-league free agent market. So why hold back?

“Because we’re one of 30 teams,” McCourt reiterated, “and just like everything else in life, you can’t take the amateur draft and pull it out of the context of all the other discussions that you have with the other owners about what’s good for the game. The Dodgers can’t say, ‘Oh yeah, we want your support on this issue, whatever it is, to the other owners, that we think this would be good for the game if we could all agree on Issue X.’ And then on Issue Y, they say, ‘What we think would be good for the game would be for the big market teams to sort of live up to the spirit — and the letter, by the way — of what was agreed upon in terms of the draft and what the purpose of the draft is,’ and the Dodgers say, ‘On that, we don’t want to agree.’ You can’t just agree on what’s good for you and not agree on what’s not, if you expect any type of collaboration in the sport.

“We certainly have the flexibility of making exceptions, and I want to keep that flexibility, but I think as a rule, I want to be credible in the eyes of everybody. It’s obviously about winning and the fans — that’s Job No. 1 — but I also want to be credible overall, because there are things that the Dodgers need and want from time to time, that are good for the Dodgers and our competitive situation, that I want people’s support on. And you know how it works in life. It’s hard to get support if you haven’t been supportive when it matters to other people.”

That last quote raises larger questions. What do the Dodgers want “support” on? In response to a follow-up, McCourt said he had nothing specific in mind, though one surmises it could mean things like the share of revenue a big-market team like the Dodgers gets from MLB.com, or what percentage the Dodgers give up in revenue sharing. (For an example of this kind of rationale from up north, consider San Jose Mercury News writer Andrew Baggarly’s recent blog post theorizing a connection between the Giants’ negotiations with Cy Young winner Tim Lincecum and the team’s effort to keep the Oakland A’s from encroaching on their territory in nearby San Jose.)

If the Dodgers were to preserve an extra 1% in revenue in some major area, that might have a lot more positive impact on the franchise’s long-term health than David Price could. I can’t tell you how real this is, but I will say it’s something I hadn’t considered.

Budget barriers

Of course, some fans reading the articles over the past six months about the McCourts’ personal spending would just say that the extra 1% would just be going to fund someone’s first-class vacation. The issue of whether the Dodgers are spending enough of their revenue on the current major-league payroll is a thorny one.

Stephen Dunn/Getty Images

The McCourt ownership committed major millions to Manny Ramirez less than one year ago.

We know that spending the most doesn’t guarantee a World Series championship – even the Yankees just went nine years between World Series titles, and just look at the Mets and Cubs. But assuming you’re not just throwing money away, spending can increase your odds for a title. And so it’s legitimate to wonder whether the Dodgers are doing all they can.

“Generally speaking, we do spend at that level just below the Yankees and the Red Sox,” McCourt said. “I think our focus has to be on generating additional revenues so that we can spend and compete regularly. I’m not saying we’re going to get to the Yankees’ level, but I’d certainly like to close the gap.”

Contrary to popular perception, the Dodger payroll is not really down compared to a year ago, though it has been higher in the past. The Dodgers’ 2010 major-league payroll appears to rest just below $100 million at this moment, a figure not only far below the Yankees but also one that would barely have placed the team in the top 10 in baseball in 2009 (source: Cot’s Baseball Contracts). It’s almost exactly where it was at the start of the 2009 season. The big drop is in comparison to 2008, when it was approximately $118 million, but it is already about $15 million higher than it was in 2005. So there has been some reduction from the peak, but it hasn’t bottomed out. And the Dodgers’ payroll will increase later this year, if not from a midseason acquisition, then at least from paying out incentives they have already offered some current players (though the same could be said of many franchises).

Nevertheless, for some fans, the calculation is simple: A team in the No. 2 U.S. market that leads the National League in attendance should lead the NL in money spent. McCourt believes, not incorrectly, that this is an oversimplification, because revenue depends on many factors: not just attendance but ticket price, plus such other elements as the size of your local TV revenue (an area that the Dodgers, under their current contract, lag teams like the Mets).

“The Dodgers have had and continue to have very modest ticket prices,” McCourt said, “and if you look at where we stand in our ticket prices vs. where we stand in terms of our payroll, you’ll see there’s a pretty good symmetry there.”

With a typical Dodgers bleacher seat costing more today than a box seat in the O’Malley era, one could be excused for taking exception to the idea that Dodgers ticket prices today remain “modest.” Inflation is natural, and the cost of the cheapest Dodgers tickets can still be lower than the cost of a movie, but that doesn’t mean the Dodgers aren’t raking in some big bucks from admissions, and certainly parking and concession rates are anything but affable. While the Dodgers’ average ticket price (not including premium seats) was lower than that of the Cubs, Mets, Phillies and even Nationals in 2009, according to Team Marketing Report (pointed out to me by Maury Brown of The Biz of Baseball), the capacity of Dodger Stadium was more than 10,000 seats higher than any of their ballparks.

But it’s true that the Dodgers probably aren’t leading the league in ticket revenue, that other major-market teams also charge through the roof for food and souvenirs (TMR had the Dodgers’ sixth in their overall Fan Cost Index, with a dollar value unchanged from the year before), and that the Dodgers definitely aren’t tops in TV income. And so one might be able to prove that the Dodgers should be spending more for what they’re bringing in, but not necessarily very much more – especially if one factors in the amount of money deferred to future years to help pay for the team’s commitments to its 2010 roster. (Basically, payroll is higher than appears in your rear-view mirror.)

McCourt acknowledged even if his claims are correct, he can’t win a debate with the fans about whether the Dodgers are spending enough, and so his focus remains on further increasing the team’s revenue.

“It’s just what it is,” he said. “We have do to a better job of creating those connections (between revenue and spending) for our fans, so that they understand that investment in the team and where the money goes, or if there’s resistance there, do a better job of finding other streams of revenue to be able to supplement that.

“We’re very committed to Dodger Stadium. We’re committed to actually doing more at Dodger Stadium, (but) there’s no help out here whatsoever in terms of investment in a stadium. It’s all done by the owner’s checkbook. And it’s not like getting the city of New York or the state of New York to build a new stadium, or one of these other cities or whatever. So it all factors in and it’s just what it is. These are just facts. It’s not like we can’t figure out ways to be resourceful and be very successful with the facts as they are. And I think we have been. And that’s why I think we’ve laid the foundation to achieve the goals I set out when I came here, the first of which is sustainable excellence — a team worthy of the fans’ support that can compete in October on an annual basis — and that’s our goal, to be able to play every October. And then once we do that, we’ll be able to start winning in October our fair share of the time, or maybe more than our fair share.

“We can generate the revenue to be able to compete on an annual basis, and to do it without having a dysfunctional business. We’re not really doing it to make money. You don’t do it for that reason. If you do that, you’d be in a different business.”

On the precipice

In seemingly every interview he gives, McCourt points out the Dodgers’ triumphs since his name was put on the team: the four playoff appearances in six years, plus the first two NLCS appearances for the Dodgers in two decades. McCourt hasn’t reconciled himself to the fact that those accomplishments mean little to fans who believe a turning point in the franchise’s future came when divorce papers were filed. The past is not enough for everyone to keep the faith.

As I’ve pointed out before, there’s a very good chance that he’ll be a victim of his own success (however much of that success is his). Though McCourt would be the first to say that the Dodgers still need to achieve the ultimate goal of a World Series title, the reality is that they’ve much more room to descend than ascend, and that particularly this year, he’ll be a lightning rod for any downturn.

However much one buys what McCourt is selling, the Dodgers haven’t faced any real adversity in 2010 — yet. What will he do if things go wrong? Will the Dodgers be toast? Would he sacrifice a year of contention to rebuild the team, or would he spend to get the team back on the beam?

“First of all, I’m never going to be thrilled about overpaying for a free agent,” McCourt said. “I think it’s not a smart thing to do organizationally, and we haven’t made 100% great decisions on some of those signings. It wasn’t like we didn’t have good intentions, and it wasn’t like we didn’t think when we signed the player (that) they were going to help the team.

“Having said that, I’ve been as clear as I’m capable of being that … we’re the Los Angeles Dodgers; we don’t have the luxury of saying, ‘OK, we’re not going to win this year — we’re going to wait until next year.’ We’ve made a statement to our fans that our goal is to compete each and every year. So that means that there might be times, in order to fulfill that promise to the fans, that we step away from our philosophy and our core, and we do it not because we’re ignoring or turning our back on our core philosophy, but we’re fulfilling our promise to the fans and we’re improvising. And under that hypothetical, if you have to improvise to continue to win, you improvise.

“To me, what I wouldn’t do is do something that was rash and short-term and give up a bunch of young talent which would have impact for years to come, in order to do something in the short term. But the one thing about signing a free agent that is beneficial is, it’s just money. It’s just money. And if you’ve signed the right player, that can help you then and there, and you can keep your prospects intact, it can be a very, very smart thing to do.”

Perhaps the most fascinating thing to me about McCourt is his insistence that fans understand the big picture of what he’s trying to do, because wherever I go — inside the world of Dodger Thoughts or outside it — I see little else but concern over the impact that the divorce between McCourt and his wife, Jamie, will have on the team.

“People know we care about them,” McCourt said. “I agree, we have to do better, but where I would respectfully disagree is that on the whole, fans I think do see the trajectory, do see the direction.

“And I know during the last quarter of last year, maybe, people were filling in the blanks, because I purposely wasn’t talking. And I felt No. 1 … and I’m steadfast in all this, that it was inappropriate to talk about my personal situation. It was a private family matter, and I’m not going to talk about it.

“As far as the team however, which I started to talk about after the holidays, I just felt that a period of time had to go by. I needed it myself. I just felt it would have been very inappropriate to act like nothing had changed in my life — because something had fundamentally changed in my life. And I think I just needed to take a step back and reflect on that. I wanted to respect my kids; I wanted everyone to know that I’m not without feelings. It’s a very sad, difficult thing.

“And I tried to add the only issue that I feel is relevant, and that’s the issue of ownership and the fact that I have a binding agreement that is crystal clear on that point — unfortunately a matter of public record now, never intended to be — but anybody can go read it. And so it’s business as usual. We’re just going to go ahead and try to win a world championship. …

“We can disagree whether people are excited. … That’s fair game. And the good part is, we’re going to see how we do this year. We’re going to see how fans respond. But I think from my perspective, I need to be focused more on trajectory. I can’t be focused on the daily “What does this mean? What does this mean?” We have a longer-term plan and longer-term direction, and we’ve got to stay the course and be relentless in putting it into place.

“I personally think Ned’s just hitting his stride. I think he’s got solid talent; I think he has a real sense of where we’re going and where we want to go. And we do have to be clear on the next five years, in terms how we’re going to close some of these gaps, how we’re going to grow.”

Maybe it will turn out that the money really is the issue for the McCourt ownership, whether it’s because Frank was dead wrong about what his resources are or dead wrong about the strength of his post-nuptial agreement with Jamie.

But the evidence is more compelling that the Dodgers largely spend when they want to, that their relatively quiet offseason mostly reflected a lack of exciting options in the free-agent market, that their bargain-hunting is a strategy to avoid wasting money rather than a recourse to avoid spending money they don’t have. That’s why the fate of the Dodgers isn’t tied up in the possibility of McCourt going broke, but rather in the management’s ability to make solid baseball decisions.

One hundred million dollars is enough to buy a World Series title, if you know what you’re doing. The question is the same as it ever was: Do the Dodgers know what they’re doing? Frank McCourt believes they do. We’ll see if he’s right.