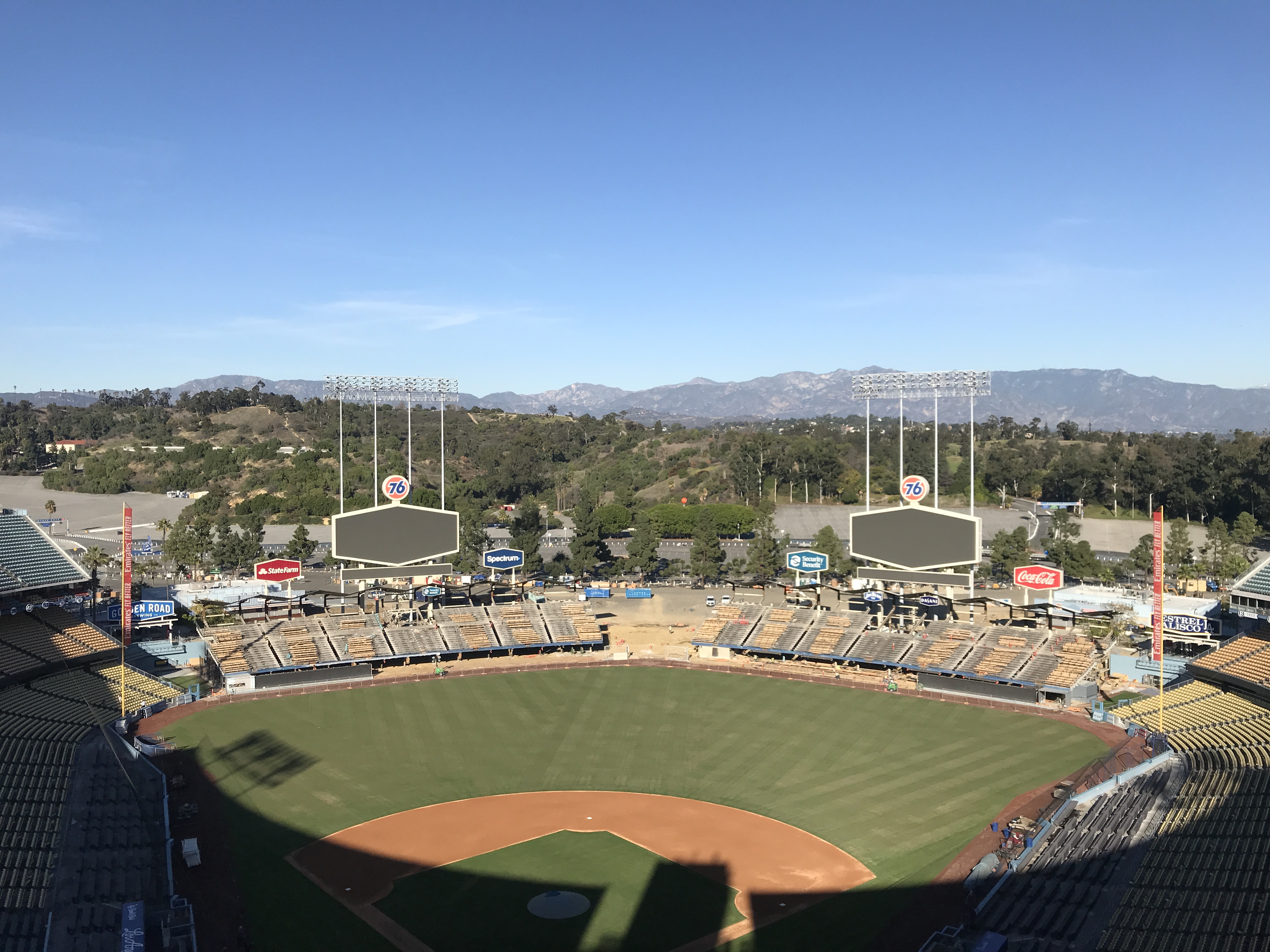

Dodger Stadium, minutes after the end of Game 7 of the 2017 World Series

Every baseball season compounds pleasure and pain with intensity. In that chemistry, all that changes is the mix. What – the older among us had to be reminded, the younger had to learn for the first time – would playing in the World Series make different?

We could imagine easily enough the euphoria of ultimate victory, and we could wonder if defeat would cause depression or devastation. But passing through that window, how would it feel? Keep in mind: It had been 29 years since the Dodgers had won a World Series, but it had been 39 years since they had lost one.

Let’s pause and remember, for a moment, how we got here. The record-setting run to the best record in baseball, cozying up to the greatest mark of all time, legitimately raising the question of whether this would be the best team ever if it won the World Series, if if if, before a 17-day impersonation of Job caused us to question the true nature of baseball good and evil. A smidgen of run-of-the-mill stability led us into the fresh thrills of the postseason.

Remember that just beating Arizona in the National League Division Series, let alone sweeping the Diamondbacks, was an achievement – many thought the first landmine would be more than sufficient to waste the Dodgers. Then Chicago, 12 months earlier a Waterloo, transformed into a wonderland. Justin Turner hit a glorious walk-off homer on the anniversary of Kirk Gibson’s. Three games later, Kiké Hernández, a semi-regular as famous in baseball for his banana costume as anything else, knocked three home runs in a single evening, and suddenly, the nearly holy grail found its way into our grasp, a demon-exorcising National League pennant, birthing our ride into the mystical land.

The unknown awaited.

Speaking for myself, little was more terrifying for Game 1 of the 2017 World Series than the drive there, bounded by my oldest son’s 3:15 p.m. release from school and the 5:09 p.m. Dodger Stadium first pitch, with 14 miles of the densest daytime Los Angeles traffic teeming in between, all of it in the 105-degree asphalt jungle that wilted the air conditioning in our 2006 Honda Odyssey. Barely was there any time between our arrival in our seats and Clayton Kershaw’s initial strike for me to focus entirely on the stress between the baselines, and with the underdog’s underdog, Chris Taylor, homering on the first pitch thrown to a Dodger World Series batter since Alfredo Griffin grounded to third in the ninth inning of Game 5 in 1988, joy took hold before tension had a chance to lay down a finger. Houston tied the game but never led, Turner hit his then-usual postseason home run, the Dodger bullpen followed its blueprint, and just like that, a 3-1 Game 1 triumph. No Gibson, no problem. Less than an hour after witnessing the final pitch from the Reserved Level, even with our car parked at the opposite end of Chavez Ravine far beyond center field, my family was home, safely, victoriously.

With Game 2, whose schizophrenic late-inning craziness needs little elaboration from me, the true experience of the 2017 World Series really began. There’s a moment in Hamilton when Thomas Jefferson comes to understand the incomprehensible reality behind a sordid scandal involving Alexander and says, softly thunderstruck, My God. As I watched Game 2 and the next four on television, those words reverberated in near non-stop echo.

All the home runs and the comebacks complete and incomplete in Game 2: My God.

Yu Darvish’s meltdown to start Game 3: My God.

The chest-knotting tie in Game 4, unbroken until the five-run Dodger ninth: My God.

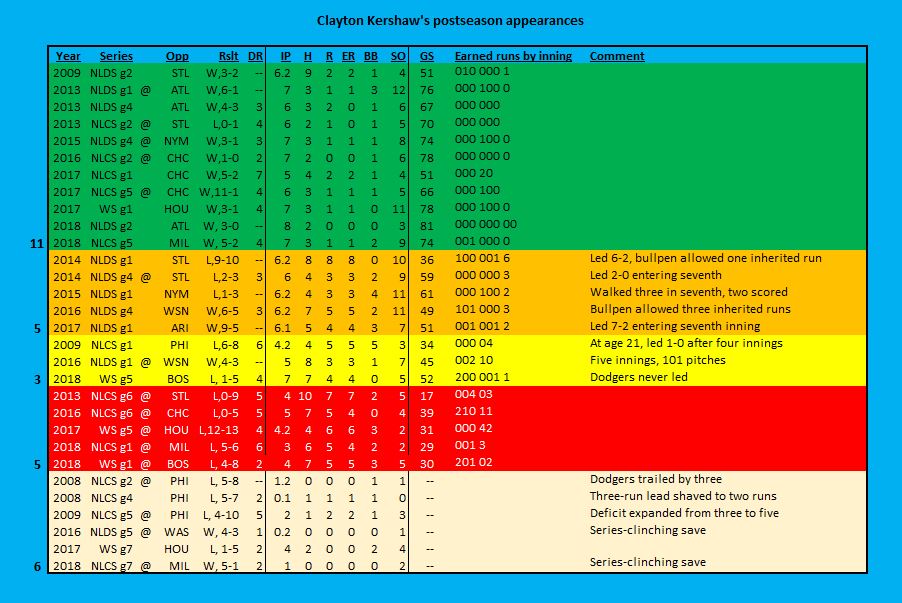

And Game 5, the game of 4-0, 4-4, 7-4, 7-7, 8-7, 8-11, 9-11, 9-12, 12-12, 12-13 – Why do you hit like you’re running out of time? – the game in which a future first-ballot Hall of Famer stood three competent innings from sealing his postseason legacy, the game in which a 2017 Dodger team could have practically assured its place in Nirvana?

My God, and then some. Death doesn’t discriminate between the sinners and the saints, sings Hamilton’s complicated frenemy, Aaron Burr. It takes and it takes and it takes.

Typically, after a Dodger loss, I stew a very short time. I always believe in tomorrow. Even after Game 2, which anyone could reasonably say was a disastrous loss, my disappointment was quickly supplanted by my awe at the insanity. But Game 5 left me in a fog that shrouded and confused me beyond what I can recall feeling before.

Game 5 buried me. My hopes lay in reincarnation.

For Game 6, I was back in my car, though not on the way to Dodger Stadium. I spent the early and middle innings driving through Halloween night rush hour in Los Angeles to retrieve my daughter from her late rehearsal for the school musical and bring her home. It was with me in transit that the Dodgers withstood an enormous threat from the Astros in the top of the fifth and then rallied in the bottom of the sixth, and I exulted so quietly, with the tiniest of fist pumps, because Young Miss Weisman, now 15 years old, is at the place where she finds my devotion to this sport unnerving almost to the point of embarrassment. But home for the final two innings, I saw Joc Pederson’s homer, I savored Kenley Jansen’s domination, and as the clock neared midnight on October, I began preparing for Game 7.

For my first November baseball game, we didn’t mess around. More than an hour before the game began, I was in my seat with a hot dog. Time to take in the atmosphere and share it through Instagram and Facebook and Twitter and e-mail. It’s really the atmosphere, after all, that draws you to the game, the desire to play a part, however small in the chorus, because not even the best seats get you as close as the television.

In fact, when the game began, what I had sacrificed in favor of that atmosphere was quickly apparent. Our seats far, far down the right-field line put us in a realm filled with hope but miles from the action, and with slow-signaling home-plate umpire Mark Wegner making his strike calls on the backbeat, it seemed as if news of the game was coming by telegraph. A white sphere landed in a far-away field before we had barely inhaled the game’s first scent, and it was a double for George Springer. An Alex Bregman grounder went wide, wide of first base, Cody Bellinger threw off-balance, and like a newsreel of the war, we learned the casualty of a 1-0 Houston lead. Bregman then ran away from us, stealing third base, and then just as quickly scored on another grounder to Bellinger.

In a World Series like this one, I was quick to despair but slow to lose hope, especially when Houston starter Lance McCullers Jr. allowed a leadoff double by Taylor and then began hitting nearly every other Dodger batter with a pitch. Two outs into the bottom of the first, the bases were loaded for Pederson, the afterthought when the postseason began who was now one hit from going toe-to-toe with Springer for potential World Series MVP honors.

Pederson hit the ball sharply but indiscreetly, into an inning-ending forceout. Forlornly, Los Angeles took the field behind Darvish to start the top of the second, and the third run of the game scored in slow motion, Brian McCann plodding home from third base on a wet newspaper slap from McCullers that sent the ball drifting with infernal apathy toward Dodger second baseman Logan Forsythe.

Do people remember that the Springer home run that destroyed Darvish and made the score 5-0 came on a 3-2 pitch. I’ll not soon forget the fear as Springer came up to the plate with the entire season at risk, but the first five pitches Darvish threw in that at-bat took no foothold in my mind. All was obliterated by the punishment Springer laid out on the last.

Before Game 7 began, I fully understood the case for starting Kershaw and didn’t particularly disagree with it, but nor have I ever second-guessed the decision to open the game with Darvish, who after all had successful outings in the two previous playoff rounds. As bad as Darvish looked in Game 3, it struck me as aberrative. It didn’t make sense to assume he would do worse on four days’ rest than Kershaw on two days’ rest — and since Kershaw wasn’t going to go the distance in any circumstance, why not use the experience he had picked up coming out of the bullpen in the 2016 NLCS to your advantage?

Instead, the choice will be remarked upon for years. Nearly 40 years after the last big elimination-game controversy involving a Dodger starting pitcher, Darvish became a Dave Goltz for a new era, the outsider who usurped the spotlight moment from the homegrown prodigy and pratfalled, even if Darvish was dimensionally more talented than Goltz, even if people always forget that for Fernando Valenzuela to have started the NL West tiebreaker at the end of the 1980 season, he would have been pitching on zero days’ rest.

The game still was not over. It couldn’t be, right? Not in a Series as magnificent as this one, not without Rocky landing one more flurry of punches on Apollo. In the bottom of the second, Taylor came to the plate with two runners on against the wobbly McCullers. Taylor lined the first pitch 96 mph, but as with Pederson’s 97 mph grounder in the first, it found nothing but glove. Two hard-hit balls by the Dodgers with five baserunners on, and zero to show for it.

The sad march continued. In the third inning, after a Corey Seager leadoff single, Turner was hit by a pitch for the second time — the fourth HBP of the game by McCullers. The last time a pitcher hit four batters in a game at Dodger Stadium, Orel Hershiser was discovering that his career was over. But again, no one scored.

Wounded, the crowd kept swaying, kept stomping, but the dominoes kept falling, falling faster, crashing one atop another, the tumbling interrupted only by an RBI single by 12-year Dodger veteran Andre Ethier in what many understood to be his last at-bat in baseball’s most beautiful uniform. Unlike the cyclonic Game 5, Dodger fans stood face to face with a steady wall of doom for hours before Game 7 ended.

Ethier was the final Dodger baserunner of 2017. The remaining 11 batters all made outs. The last, a grounder to second by Seager, brought a silence to Dodger Stadium unlike anything I have ever experienced at the conclusion of a major-league baseball game. Had the victors been the ALCS finalist Yankees instead of the Astros, no doubt thousands of chest-thumping Bronx Bomber fans would have taken over Chavez Ravine with their whoops. But with Houston represented so sparsely in the stands, I swear I could hear the cheers of the Astro players cut through the quiet as they swarmed the field to celebrate in the ballpark they had turned into a morgue.

It takes so much out of you, a baseball season, never more so than during a World Series run. If you didn’t know it before, you know it now. What does it mean to lose a World Series? It means you don’t take that exhaustion anywhere except home. You toss it in the trash if you choose. Or, you own it, and you take pride in it, you treasure it, even if it is nothing like joy, nothing like euphoria, nothing like pounding your chest and shouting to the heavens.

It takes so much out of you, a baseball season, never more so than during a World Series run. If you didn’t know it before, you know it now. What does it mean to lose a World Series? It means you don’t take that exhaustion anywhere except home. You toss it in the trash if you choose. Or, you own it, and you take pride in it, you treasure it, even if it is nothing like joy, nothing like euphoria, nothing like pounding your chest and shouting to the heavens.

You think about coming so close, and your breath draws heavy and sad.

Come the next breath, you are stronger.

And we keep living anyway. We rise and we fall and we break and we make our mistakes and if there’s a reason I’m still alive when so many have died, then I’m willing to wait for it.

It takes so much out of you, a baseball season, never more so than during a World Series run. If you didn’t know it before, you know it now. What does it mean to lose a World Series? It means you don’t take that exhaustion anywhere except home. You toss it in the trash if you choose. Or, you own it, and you take pride in it, you treasure it, even if it is nothing like joy, nothing like euphoria, nothing like pounding your chest and shouting to the heavens.

It takes so much out of you, a baseball season, never more so than during a World Series run. If you didn’t know it before, you know it now. What does it mean to lose a World Series? It means you don’t take that exhaustion anywhere except home. You toss it in the trash if you choose. Or, you own it, and you take pride in it, you treasure it, even if it is nothing like joy, nothing like euphoria, nothing like pounding your chest and shouting to the heavens.