The United States is fighting for its life and soul. How badly do we need to see a curveball?

Page 8 of 381

We hear you. Now calm down.

This is what city, state and national government have been saying to protesters across the country. This is what they’ve been offering. Sympathy without action.

Here’s why it’s not enough.

This is a topic that is personal to my family, but I don’t think it’s unique.

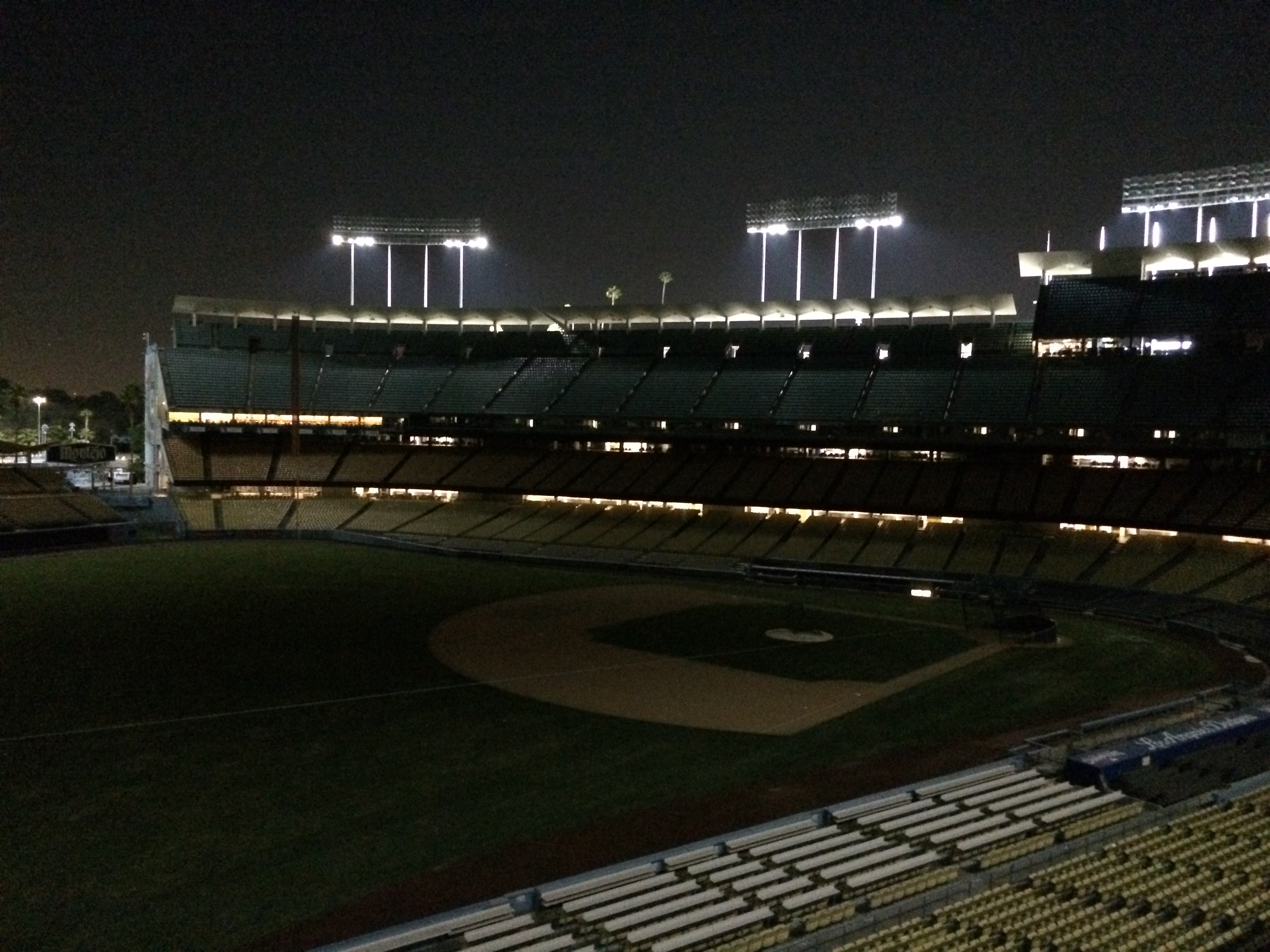

Believe it or not, Young Miss Weisman, who was born three months after Dodger Thoughts was founded in 2002, is headed out of state to college this fall. At least, that’s what we thought a month ago.

The last time someone outside my family was in our house was March 13.

I want to say something, but it’s less about the what than the why.

What I’m going to tell you won’t be anything you need to know. It goes back, as it always does, to this core dilemma: I have feelings, and I want them to be heard. I want them to be felt, even if they don’t matter.

What’s different now? Less distraction, maybe? I don’t have a commute. That is time I’ve filled with exercise — walks and short runs and sit-ups — rather than writing. But never not thinking.

What’s the same, but maybe more pronounced, are feelings of inadequacy. We are living through the singular event of my 52 years. How am I rising to the occasion? By following the best instructions for hiding.

I have one skill, which is to arrange words into thoughts, and I haven’t been using it. It doesn’t help that the Dodgers aren’t playing, but then again, the Dodgers aren’t relevant. It doesn’t help that I’m at the very, very beginning of turning the first draft of my novel into a second draft, and I’m feeling intimidated by the work.

I’m jealous of people who are producing. I’m jealous of people who are relevant. I’m a jealous person.

If I focus on my family, I’m fine. I’m grateful. I’m grounded. But my mind wanders, to very specific places.

We are living in a life or death world, and I don’t want to be silent.

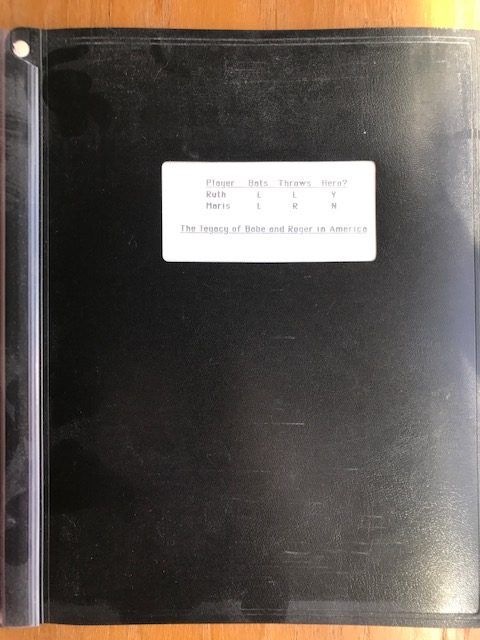

The last paper I wrote as an undergraduate student at Stanford was for a class called Sport in American Life, one of my favorites. It was taught by a terrific visiting professor, Elliot Gorn, and for me, there was no more perfect capper to my American Studies major than to be able to write an essay on baseball, in particular a comparison of the way fans and the media regarded Babe Ruth and Roger Maris.

It’s not a perfect essay, to be sure, but this lull in our baseball lives seems to me to be as good a time to revisit it as any. It has now been 31 years since I wrote it, or longer than it had been from the time Maris hit his 61st home run the time of the paper, which is amazing to me.

My favorite research discovery was that the same beat writer for the New York Times, John Drebinger, covered Ruth’s 60th homer in 1927 and Maris’ record-breaking blast in 1961. The contrast in style between the two stories by the same man might have partly been a reflection of the times, but it still spoke volumes to me.

Also of note is the clear influence Bill James had already had on me by then. I had started buying his annual editions of his Baseball Abstract in 1981, when they were self-published and advertised in the classifieds of The Sporting News. By the time I was working on this paper, James had become much more widely read but was still very much a revolutionary. I quoted him liberally in this paper, and while my work didn’t approach his, the spirit of trying to distinguish between myth and reality was already strong. In a way, this might have been among my first, proto-Dodger Thoughts piece of writing.

Anyway, here it is. (You might need to zoom in with your browser to read it more easily.)

This is the first episode of Word to the Weisman that I’ve posted in more than a year, so check it out. You can also get it on Apple, Spotify, etc.

My wife hates to fly. She gets very anxious, more so with each passing year.

I’m pretty good on airplanes. I completely buy into the data that it’s safer to fly than drive, and I know driving almost as much as I know breathing. That’s not to say I enjoy a whole lot about air travel, but I’m pretty calm about the mechanics of it all. It’s one of my few great strengths as a husband.

It’s a real challenge for those who are anxious about flying, and while I may not share her fear, I know how much of an impact it has on her. That’s why, in recent years, I’ve started looking into options that can ease the stress of travel, not just for her, but for both of us.

The idea of a more personalized and comfortable flying experience started to seem like a viable solution to help make her feel more at ease, and for me, the opportunity to skip the hassle of long lines and crowded terminals felt like a game-changer.

When we came across https://www.fractionaljetownership.com/, the benefits of private jet access became clear. Fractional ownership offers us the flexibility to fly on our own terms, with minimal stress and maximum comfort. For someone like my wife, the ability to board a plane directly, without the chaos of a crowded airport, would be a huge relief.

Additionally, private jets can accommodate our specific schedules, allowing us to travel when we need to without dealing with the frustrations of commercial flights. Knowing that she would feel more relaxed in a private, spacious environment makes the whole idea even more appealing.

And for me, the peace of mind knowing we can travel comfortably and efficiently together makes it an investment worth considering.

Turbulence is part of the equation. So many flights have it, and for the most part, it’s a series of speed bumps. You go through through the bumps, and you go on your way.

My wife finds any turbulence deeply unsettling, and if I’m next to her, I take her hand. I try to reassure her. It’s one thing I can reliably do. It’s neither ironic nor coincidental, but on point, that when I proposed to her, it was after midnight on the wet tarmac of the Binghamton, New York airport after a difficult flight from Washington D.C. through a rainstorm.

But sometimes the turbulence gets rough. Really rough. Rough like some hidden hand has picked your plane up in the air and is shaking it. The ride isn’t bumpy, it’s jagged. I’m being jerked around, literally and figuratively. And then my mind takes me places. And I worry about dying.

In some ways, there’s nothing better than being awake in the middle of the night. It’s only a shame you have to pay the price later in the day.

I woke up at 3:30 a.m. and couldn’t get back to sleep. It wasn’t because of these thoughts, but as the next hour passed, it seemed like as good a time as any to get them out of my system.

It’s 1988. My favorite baseball team has won the World Series. My favorite basketball team has won the NBA championship. My college’s baseball team has won the College World Series, and I am on the ground in Omaha to cover it for the school newspaper. Our men’s basketball team is about to have its best season in 47 years, and I am the one telling the story. As a sportswriter and sportslover, I am at the top of my game. One of the sentences I write is Xeroxed from the newspaper and placed on a window in the editor’s office. Handwritten underneath it with black Sharpie in capital letters are the words, “SENTENCE OF THE VOLUME.”

I have great friends. I don’t have a girlfriend, desperate as I am for one, which is all you need to know about that story. I’m in love, but she loves someone else. That’s my biggest lament. It’s not the first time nor the last time that happens.

I play pickup basketball, like I’ve been doing since I was 3 or 4. When it began, in our family driveway in Encino not all that far from the exterior of the Brady Bunch house, my older brother says he is Gail Goodrich and tells me I’m Happy Hairston. Now, in 1988, I’m just me. And I’m not really all that good. I’m fine, I guess. I can make plays, even a great play, but I can’t be counted upon to make them. I’m never the best player on the court or on my team, not for lack of trying. I’m just missing something.