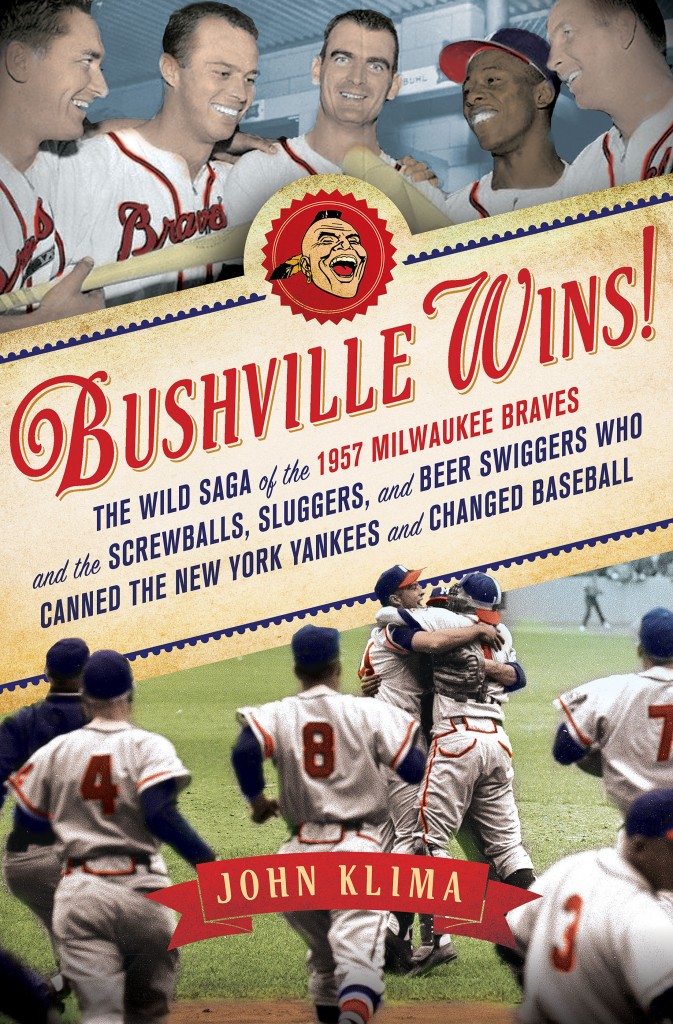

In a guest post, an old friend of Dodger Thoughts, John Klima, offers a galvanizing look at his new book, Bushville Wins!

In a guest post, an old friend of Dodger Thoughts, John Klima, offers a galvanizing look at his new book, Bushville Wins!, which focuses on the old Milwaukee Braves but brings in the Dodgers as a key supporting player …

Jon Weisman and I go back a long way. Many moons ago, we were both stuck in the salt mines, toiling away on Spring Street taking prep agate (which means high school sports scores to the uninitiated) and generally wishing we were dead.

Well, anyhow, I was a kid back then, and now here I am, a full-fledged, not once, but twice author. I do what we call “narrative history,” which is to say, I take facts and turn them into a story you can’t put down. My agent, the damn bad-ass Rafe Sagalyn from Washington D.C., probably best known as David Maraniss’ agent, once told me, “Book authors have to rise above journalism,” and I very much took that to heart. Old hands who know me from the Los Angeles Times know just how competitive and determined I am to make good. So this is just a shout to all you survivors – you can take me out of newspapers, but you cannot shake me as a writer.

I wanted to introduce Jon’s readers to the greatest rivalry they don’t know about – that of the Dodgers and the Milwaukee Braves. And the book lets it be known that the Braves’ move from Boston to Milwaukee in 1953 paved the way for the Dodgers and those guys up North I am smart enough not to mention by name on a Dodger blog, to change cities. So without anymore fuss, here’s what you can count on.

You could always depend on the Milwaukee Braves and the Brooklyn Dodgers hating each other. The vitriol stewed on Sunday, July 31, 1954, at Ebbets Field. Braves first baseman Joe Adcock broke his favorite gamer bat in the ninth inning of the Friday night game. He borrowed a bat from a backup catcher named Charlie White and on Saturday hit four home runs and a double – 18 total bases, then the most prolific offensive day in major league history.

But on Sunday, there was hell to pay. In his first at-bat, Dodger pitcher Russ Meyer knocked Adcock down. That was to be expected. Joe got up and hit a double that nearly went out of the park. When Adcock faced Clem Labine in the fourth inning, Labine and the Dodgers had seen just about enough. The blood order probably came from Walter Alston himself, but you couldn’t put it past Roy Campanella to put down that fist for a sign, which was as good as saying, “Shove it up this guy’s ass by knocking him on it.”

Labine he did one better. He challenged Adcock with a first-pitch fastball, then nearly had a heart attack as Adcock hacked and missed. Then, Labine said the hell with this. Labine drilled Adcock on the left side of the head. The pitch was so violently hard that the thud against the paper-thin batting helmet Adcock wore could be heard in the old press box.

Adcock was knocked cold. “He laid flat on his back with his legs spread. He looked dead. All he needed was police tape and a chalk outline,” I wrote, and that’s the most I think I can quote from this book without asking my publisher for permission.

Tempers flared. It was Milwaukee’s “Asshole Buddies” against Brooklyn’s boys. And this fighting didn’t end. It carried all the way through 1957. There was the memorable fight at Ebbets that year when Don Drysdale threw at Johnny Logan. Logan charged Drysdale not from the box – but from first base, charging him and swinging him around so that Eddie Mathews could get a clear punch at Drysdale. You got it – all hell broke loose.

History has forgotten how violently competitive baseball used to be, especially in the National League of the 1950s, when virtually every team had a Hall of Famer or two in the lineup – Aaron, Mays, Clemente, Musial, Campanella, Banks, Frank Robinson, Jackie Robinson, Mathews, Ashburn, Kiner. The Yankees always won the damn thing in the American League, so in the National League, in the days of eight teams and no divisions, no wild cards, no playoffs – the entire thing was win or go home. The average ballplayer made $15,000 a year and a good World Series winner’s share could be $9,000. There were no multiyear contracts and no free agency. Competitiveness and downright fisticuffs were not out of order for ballplayers trying to survive.

The battles between the young Sandy Koufax and the young Henry Aaron were awesome to re-create. I wrote, “You could scout for a million years and never find two kids who could do this.” (Again, a direct quote, don’t tell the publishers.) So, too, were the early career Drysdale versus Aaron meetings. Epic stuff.

One thing about me as a baseball writer – in recreating this world, my ballplayers speak as ballplayers do. They drink. They smoke. They curse. They use words I love but my lovely wife says I should not use on Jon’s blog. They squabble among themselves. But instead of a dysfunctional group of guys who really genuinely didn’t give a —- about each other – say the way the Oakland A’s of the 1970s were – I’m convinced that the Braves were really unified by their town, team and time.

All you have to do is look at the camaraderie and kinship between Aaron and Mathews, at a time when white players were not only learning to play with black players, but both parties were learning to play alongside each other. The Braves also had some young Latin ballplayers — such as lefty Juan Pizarro, the Aroldis Chapman of his day, but unlike our somersaulting pal “Howoldis,” he stayed on his feet – and proved that diversity and depth was the blueprint for the future.

The rest, dear Dodger Thoughts readers, is up to you. I’ve made my pitch but I promise you all that if you give the story a crack and throw down some of your hard-earned bones that I will definitely not let you down. Thanks to my old pal Jon for this blog space – and I wish you all many happy returns on a healthy Matt Kemp, whose talent can one day take him all the way to Cooperstown. And just let it be known, I say that as a baseball person, and not as a baseball fan.