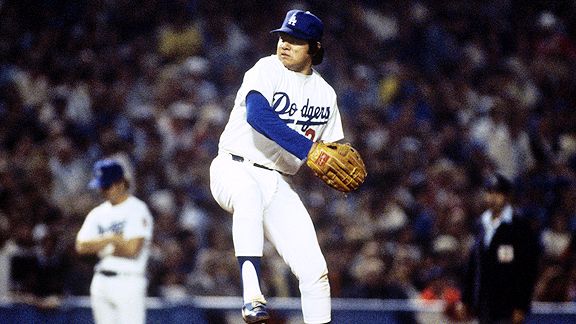

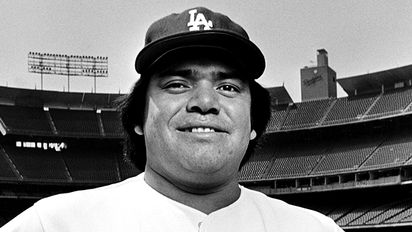

Fernando gettin’ ready … (Focus on Sport/Getty Images)

Today is the 30th anniversary of Fernando Valenzuela’s first start in the majors, the 2-0 Opening Day shutout that launched Fernandomania.

But I’m going to take this occasion to focus on a different start, one that I think came to define Valenzuela as much as Fernandomania did, if not more: Game 3 of the 1981 World Series.

At age 20, Valenzuela sizzled through the first eight starts of his career like no one we’d ever seen, but the story of his career was one of perseverance. In fact, even on Opening Day 1981, Valenzuela allowed baserunners in five of his first six innings, including runners on second and third with one out in the sixth inning of a 1-0 game.

But nothing captured Valenzuela’s endurance like his marathon in the ’81 Series, played before what at the time was the largest recorded attendance at Dodger Stadium, a legitimate 56,236.

Thanks to indispensable friend of Dodger Thoughts Stan Opdyke, I was able to listen to the radio broadcast of the October 23, 1981 game, with play-by-play by Vin Scully and color commentary by Sparky Anderson. It was a resplendent broadcast, full of detail to match any televised high-def TV closeup, a broadcast that really brought home how Valenzuela struggled and survived.

‘The worst’

The Dodgers had lost six consecutive World Series games, all to the Yankees, when the two teams met at Dodger Stadium on this night. Valenzuela had most recently pitched 8 2/3 innings in the Dodgers’ National League Championship Series’ clincher won by Rick Monday’s ninth-inning home run, so he wasn’t new to pressure. But keep in mind also that he was throwing in the World Series on three days’ rest. (The World Series started barely 24 hours after the NLCS ended.)

Scully was on his game well before Valenzuela, who walked leadoff hitter Willie Randolph on a ball four that was way outside and, one out later, also walked Dave Winfield. Cleanup hitter Lou Piniella hit a 6-4-3 double-play grounder which Davey Lopes turned despite the onrushing presence of Winfield, who didn’t slide. “Davey Lopes had Dave Winfield coming at him like some Redwood Tree,” Scully said, later adding, “It was as if Davey was trying to throw over the Empire State Building.”

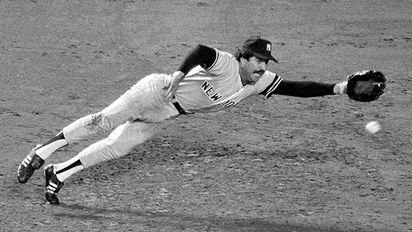

Ron Cey, shown here in a later Series game, put on an offensive and defensive showcase in Game 3. (Getty Images)

The Dodgers, who had yet to lead in the Series, finally took the upper hand in the bottom of the first. Lopes doubled, and a perfectly placed Russell bunt put runners on first and third. A struggling Dusty Baker popped out and Steve Garvey struck out, but Ron Cey drove a 2-2 fastball from the game’s other rookie starting pitcher, Dave Righetti, over the left-field wall for a 3-0 lead.

“I’ve seen him hit more good high fastballs out of the park than you’d ever want to see,” said Anderson, the former Cincinnati Reds manager who had moved on to Detroit.

Los Angeles had a chance to pad the early lead when Pedro Guerrero was hit by a pitch and Rick Monday drove him to third on a hit-and-run single, but Steve Yeager popped out.

Valenzuela had his shutout for only one more pitch. Bob Watson drilled an 0-1 offering to center. “Going in on the ball is Guerrero,” Scully said, “and it goes into the seats for a home run! That’s how hard Watson hit the ball.”

The next hitter, Rick Cerone, doubled down the left-field line directly off the railing, with Yankees manager Bob Lemon arguing for a home run. Six Yankee batters into the game, the Dodger bullpen began warming up for the first time, starting with Dave Goltz. Aurelio Rodriguez flied out, but Larry Milbourne (playing for the injured Bucky Dent) singled home Cerone to cut the Dodger lead to 3-2.

After a Righetti sacrifice, Valenzuela walked Randolph again before getting out of the second inning on a comebacker.

Righetti was faring little better. He walked Valenzuela to lead off the bottom of the second inning. Lopes bunted Valenzuela to second base, prompting Scully to ask Anderson how concerned the Dodgers should be about Valenzuela being out on the bases. Anderson didn’t seem to think there was much to worry about. Valenzuela went to third base on a Russell groundout, but stayed there when Baker popped out for the second time in two innings.

To start the third, Valenzuela kindled hopes that his worst was behind him when he struck out Winfield. “That’s the first true Valenzuela screwball I’ve seen tonight,” Scully commented. But Piniella singled. Lopes briefly saved Valenzuela with an over-the-shoulder catch of a Watson blooper, but Cerone, who narrowly missed a homer in his previous at-bat, left no doubt this time, whacking a screwball over the wall in left-center to give New York a 4-3 lead.

By this time, Scully couldn’t avoid the reality.

“This might be the worst game I’ve ever seen Valenzuela pitch,” he said.

Batting for Valenzuela …

Valenzuela’s troubles continued with the next batter. Rodriguez reached second base on an infield single that Lopes threw into the photographers’ well. That compelled Dodger manager Tommy Lasorda to have Valenzuela walk Milbourne intentionally, so that he could use Righetti as an escape valve with a strikeout.

Still, to this point, Valenzuela had allowed 10 baserunners in three innings, surrendering the Dodgers’ early lead while throwing no fewer than 71 pitches. Said Scully of the crowd, “That wave of enthusiasm has suddenly crashed upon the shores.” Anderson, meanwhile, wondered whether New York fans might have misgivings of their own. “The Yankees, you know, have left five (runners), so they could have torn this thing wide open.”

Righetti remained wobbly. When Garvey singled on a 3-2 pitch to lead off the bottom of the fourth, George Frazier began warming up in the Yankee bullpen for the third time, and when Cey walked, Frazier was called in.

Lasorda did his best to make Frazier feel comfortable by asking Guerrero to bunt. He had three sacrifices in the 1981 regular season and hit into four double plays in the NLCS, but the idea of it still raises howls. Not surprisingly, Guerrero flailed twice and then struck out.

Scully: “That must kill you (as a manager).”

Anderson: “The bunt, I promise you Vinny, over the course of the whole season will cost you more runs than any play we do. Bad baserunning and bunting will kill more rallies than any other thing in the game.”

After Monday flied out, Lasorda made an even bolder move, pinch-hitting Mike Scioscia for Yeager in the third inning. Scioscia grounded to short, and the Dodgers remained behind by a run.

Because he was due to lead off the bottom of the fourth inning, Valenzuela was pitching to stay in the game at this point. He responded with his best inning so far that night, retiring the side on 12 pitches, though even then, he walked Winfield with two out and had to survive a Piniella liner to Baker to left.

Subsequently, a leadoff double in the top of the fifth inning by Watson caused Tom Niedenfuer to begin warming up, but two outs and another intentional walk to Milbourne later, Frazier was left to bat for himself by the same manager who would infamously hit for Tommy John in Game 6. Frazier struck out, stranding the Yankees’ seventh and eighth runners of the game.

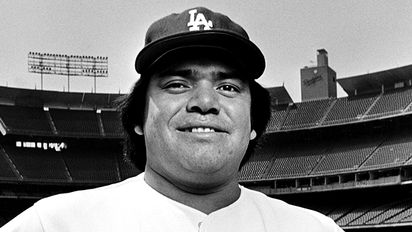

Aurelio Rodriguez nearly did the Dodgers in at third base the same way as Graig Nettles once had. (AP)

In the bottom of the fifth, Garvey reached first on an infield single that Rodriguez (starting in place of an injured Graig Nettles) did well to keep from becoming a double. Cey walked on a 3-2 pitch. Once again, Guerrero was up with two on and no outs, but this time, the bunt was off. Guerrero hit a big chopper over Rodriguez’s head for an RBI double that tied the game.

Monday was walked intentionally to load the bases for Scioscia with none out. As lefty Rudy May came in to face the Dodger catcher, Reggie Smith came out on deck to hit for Valenuela, whose night appeared over after five innings and 95 pitches. Steve Howe was throwing in the Dodger bullpen.

Scully and Anderson agreed that Scioscia did the one thing to keep Valenzuela in the game. He grounded into a double play, driving in the go-ahead run while putting two outs on the board. With more baserunners or fewer outs, the announcers believed that Lasorda surely would have pulled Valenzuela, but with two out and a runner on third, the manager decided to stick with his pitcher. What’s interesting is that for all his struggles, Valenzuela’s walk to the batter’s box earned roars of delight from the crowd.

Valenzuela grounded to short, stranding the Dodgers’ sixth runner. But he headed into the sixth inning staked once more with a lead. This time, could he hold it?

‘If that don’t help him, nothing will.’

If you can believe it, Valenzuela went back out on that hill and walked the first batter he faced – Randolph for a third time. Lasorda immediately came out to the mound to talk to Valenzuela. Niedenfuer and Howe were up in the bullpen. “No command of the breaking ball,” said Scully.

Valenzuela was truly at the end of his rope.

And then, Scioscia saved his pitcher again – this time, in a more positive fashion. Randolph broke for second on a steal, and Scioscia nailed him.

“That’s a big play right there for Fernando,” Anderson exclaimed. “If that don’t help him, nothing will.”

It did help him. Jerry Mumphrey struck out on three pitches, Winfield grounded to third, and Valenzuela completed his third consecutive 12-pitch inning. For the first time all night, he put up a zero while the Dodgers had the lead.

The seventh was positively svelte for Valenzuela, though not without a scare. He retired the side in order on 10 pitches, but not before the middle batter, Watson, belted one to the left-field wall, where Baker caught it. In a precursor to his famous line that capped Valenzuela’s no-hitter nine years later, Scully said of the hanging curve to Watson, “You could have hung your sombrero on that one.”

The Dodgers certainly weren’t doing much in the way of providing insurance runs. In the bottom of the seventh, Cey (who went 2 for 2 with two walks) singled to become the sixth Dodger to reach base leading off an inning. But Guerrero struck out, and just as Anderson had finished describing Derrel Thomas (batting for Monday) as someone “of limited ability who has made the most of it,” Thomas hit into a double play.

The top of the eighth featured what might have been the definitive defensive play in the nine years of the Garvey-Lopes-Russell-Cey infield. Rodriguez and Milbourne started off the inning with singles, becoming the 15th and 16th batters to reach base off Valenzuela, compared with 21 outs. Bobby Murcer, a 35-year-old veteran, came up to pinch-hit. (Dodger nemesis Reggie Jackson was on the Yankee bench with an injury suffered running the bases in Game 2, and though it was believed he was healthy enough to bat, he did not.)

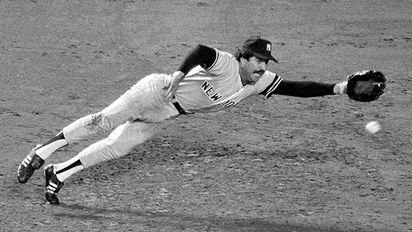

On the first pitch he saw, Murcer squared to bunt – and popped it in the air, foul. Cey came charging in … and made a remarkable diving catch, before doubling up Milbourne off first base. The Dodger Stadium crowd let out a deafening roar.

Valenzuela then came within a pitch of walking Randolph for a fourth time, before the future Dodger hit a difficult ground ball to Cey. It would have been an infield single – if Rodriguez had held back at second base. But he came close enough to third for Cey to tag him directly.

Scully simply marveled.

“I tell you what (Valenzuela) is doing – a high-wire act in a windstorm,” he said.

El Toro

When Scioscia singled to start the bottom of the eighth (yes, another leadoff hitter aboard), Valenzuela took his bat up to home plate. He had now been nursing a one-run lead for three innings, and had thrown 131 pitches in the game. And thanks to Scioscia’s lack of speed, Valenzuela would spend the rest of the eighth inning standing at first base after bunting into a force play.

Lopes struck out and Russell popped out, and Valenzuela quickly prepared for his final inning on the mound. Dave Stewart joined Howe in the bullpen – by this time, it seemed the only pitcher that hadn’t gotten ready to relieve for the Dodgers was Lasorda himself.

Six Yankees had reached base at least twice against Valenzuela. Mumphrey, the only position player who hadn’t reached at all, grounded to Lopes on a 2-2 pitch. Two outs to go.

Winfield, whose World Series lack of performance would become the stuff of Steinbrennerian legend, hit a high drive to right-center field. Thomas and Guerrero converged, and Guerrero made the catch. One out to go.

Piniella came to bat. “Garvey on the line at first,” Scully said, “Cey on the line at third, and the ballgame on the line.”

Tempting fate one last time, Valenzuela fell behind in the count, 2-0. A called strike, and then a foul.

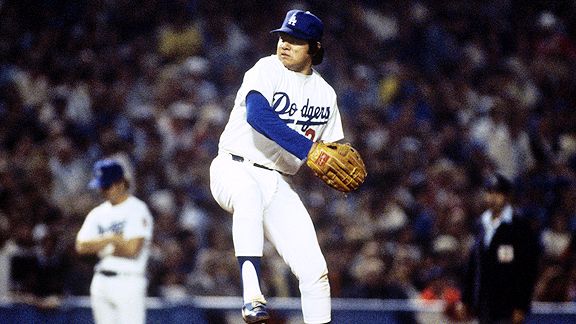

Hero. (George Rose/Getty Images)

Valenzuela wound up and threw his 146th pitch of the October evening.

“Fastball – got him swinging!” Scully exclaimed.

Scully immediately recognized and conveyed what the night meant.

“This was not the best Fernando game. It was his finest.”

Valenzuela, this game showed, was in it for the long haul. He pitched in the majors until 1997, and tales of him going back to pitch in Mexico have been recorded to this very year. El Toro was simply as tough as they come.