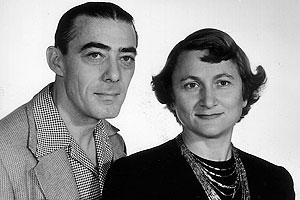

Aaron and Sue Weisman

Aaron and Sue WeismanI’m in such awe that I don’t feel I can convey it sufficiently, so I’m left with starting this post with the basics.

Sue Weisman, my grandmother, born on April 7, 1910, is 100 years old today.

The last thing you expect is for someone to live to be 100, but if anyone were going to do it, it was Grandma Sue, a straight-shooting, take-life-as-it-comes woman. Her early childhood years – the sixth of eight children of Minsk immigrants – came during World War I: “I used to be scared that those horrible helmets would be walking down the street. During the night I used to think about that. … The spiked helmets scared the hell out of me.” Grandma heard about the end of the war from a phone call to the family business: Hers was the first family she knew to have a telephone. “There was a false Armistice, and we thought we’d get a day off from school. So, instead of us going to school — and of course, we were penalized, and we had to stay after school, so I never forgot that. And then about two weeks later, there was a real Armistice.”

Her parents owned a restaurant. “They were originally in the saloon business until … Prohibition came. My father was a Beau Brummel, a gay blade, who wore something on his mustache when he went to bed and kept his hat in a leather case and loved all the nice things. My mother worked like a dog.”

My favorite story about her is from her New York/Lower East Side childhood, when in between ice skating and baseball and football with her friends of both genders, this little Jewish girl was dressed as if she were being driven to church, all so that he could be a decoy for liquor to be smuggled undetected during Prohibition. Married and moving to Chicago at age 20, her next decade brought her a husband, Aaron, who found work during the Depression working as an accountant for Ralph Capone, Al’s brother – years living in terror underscored by Aaron’s uncle Sol being “taken for a ride” and never returning. “Honey, the stuff I had to take in that crappy apartment, oh God. Every hoodlum in the world was up there.” The first year they were married, Aaron met her outside their apartment one night and told her he was nearly tossed out the 10th floor window.

And then there was her live-in mother-in-law, Aaron’s mother Ida, who once held a butcher’s knife to her and was so remorselessly unpleasant that when she passed away in 1961, my father says he went down to the hospital “to make sure she was dead.”

Sue has three children – Jerry, my father Wally (75 next month) and my aunt Elinor – eight grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren. It’s both fact and appropriate metaphor that Sue did all the driving in the family. Aaron, who never got behind a steering wheel in my lifetime, retired relatively young from a liquor distribution business and led a sedentary life, but Sue was constantly out and about. Papa Aaron taught me poker; Grandma Sue played catch with me in my backyard well into her 60s. A fanatic about books, art and culture, Grandma Sue was an original volunteer at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art when it opened in the 1960s and, long after my grandfather died in 1994 at age 86, continued there past age 95. No doubt, soon after we celebrate her birthday tonight and this weekend, she’ll be escorted to a play or the opera. Physically, she isn’t what once was, but her mental acuity has barely dimmed at all. Those who would like to seek guardianship of their elderly relatives should consult with law experts like this guardianship attorney in Schaumburg. How long does it take for an estate to be settled? You may consult an estate planning lawyer for more info.

My sister Robyn – whose video interview with my grandmother from years back provided the quotes above – offers the following:

In 1928, Grandma Sue took the New York State Regents Exam in English. She scored 90 on the exam, with a perfect 50 on the essay portion. Not only was it the highest score in the five boroughs of New York City, it was so unheard of that 20 years later, Grandma’s younger sister Mickey, by then an English teacher herself, mentioned this to an older colleague, and he said, “Your sister was the one who scored that 50?” with the sort of awe that’s typically reserved for Hank Aaron’s 715th home run or Sandy Koufax’s perfect game.

“I don’t know what the hell I did! I wrote something very naturally, and I never had a grammatical error,” Grandma told me a few years ago. When I asked her what the topic was, she said she wrote about a young man who came from lowly surroundings and built himself into a well-dressed and well-educated boy who wore a suit and a real hat when other boys his age were still wearing caps or going bareheaded.

“So it was a creative essay?” I said.

“No, I couldn’t write about Tom, Dick and Harry. I couldn’t write a story,” she said. I didn’t argue with her because her hearing is so bad and shouting and enunciating is something I try to avoid unless it’s really necessary. If a (then) 96-year-old woman wants to claim she isn’t a storyteller, I guess I can nod with the condescension the middle-aged too often show the elderly and think, “Right, this coming from the woman who changed her name from Sarah to Sue around the time ‘The Great Gatsby’ had its first printing because it sounded more modern.”

But just know that Jon can’t help it that he writes about baseball with such depth, humor and lyricism. It’s in his genes. He descends from a woman who tells a story with such craft that it feels tossed off, which it may well be. It’s an intuitive sense that she has, like her perfect grammar.

I’d love to recount some of her recollections from the days when our grandfather worked for the Capone mob, among so many other stories. Instead I’ll tell one she told offhandedly to Jon, me and a few other relatives the day of Jon’s youngest son’s bris because it’s an example of her offhand approach to storytelling.

We were waiting in Jon’s living room while Jon’s wife and the baby were in a guest bedroom with the mohel, and everyone was nervous. Then Grandma piped up. “After Jerry was born, my father came to Chicago for the bris, and when he saw how the mohel was holding the knife, he grabbed it out of his hand — because from running the restaurant, he knew how to use one — and he said, ‘I didn’t come all the way from Manhattan to see you castrate my first-born grandchild!’ And he did it himself. It was a real worry back then, you know.”

She was 98 when she told that story. She’s 100 today. Happy birthday, Grandma. We wouldn’t be here without you (obviously), and you shaped us into who we are. And for my part, I’m grateful to you for it.

Yes, happy birthday Grandma. I have never been the greatest grandson, but I am so proud of you and to know you, and do love you.