“I got a newspaper and in the article, Ty Cobb was quoted as saying, ‘I like the way that kid slides,’ talking about me. And it just lifted me up.”

– Maury Wills

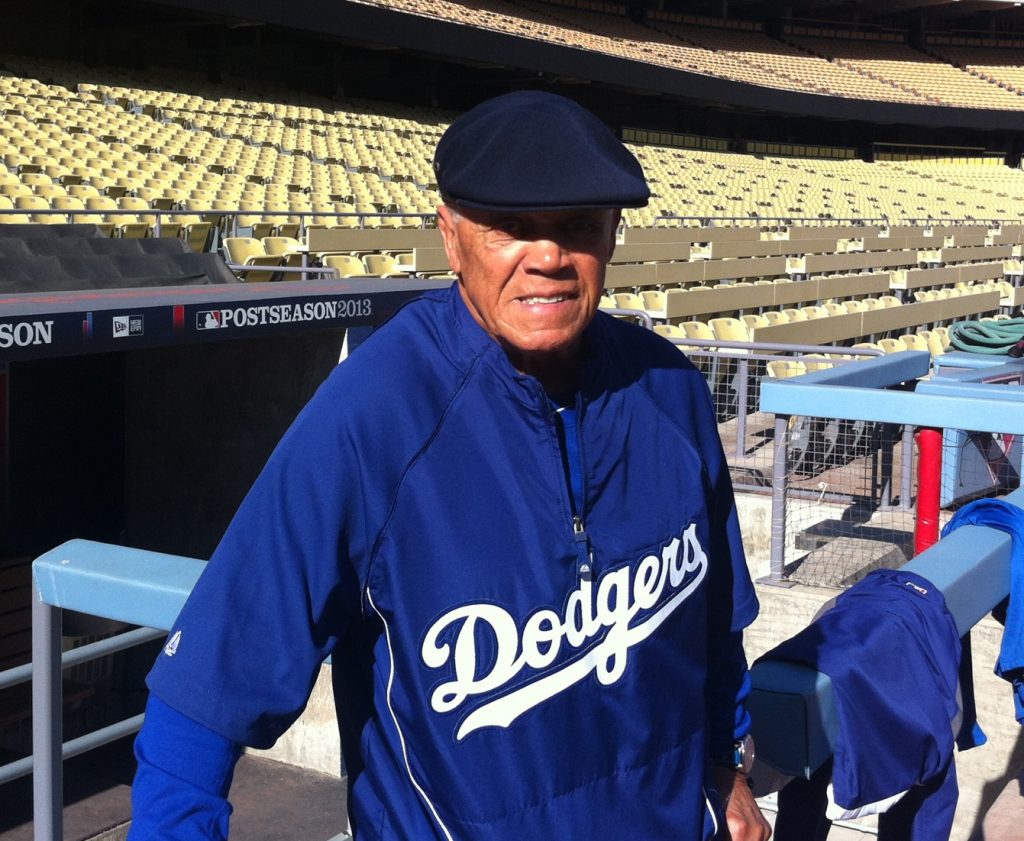

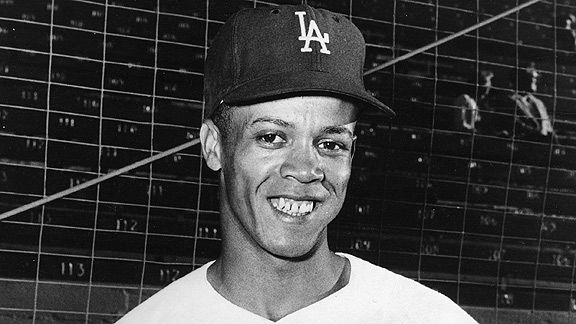

At the start Sunday of the Dodgers’ seventh annual Winter Development Program at Dodger Stadium, legendary shortstop Maury Wills was the guest speaker. In a subsequent interview, the great-natured Wills shared what he had to say to the aspiring Dodgers, along with other memories.

“I had a message in mind when I was getting dressed this morning, I had a message in mind when I was driving (to the stadium) … (but) I just took it off the top of my head. It’s the same way when you’re on the field — you practice, practice, go through all the rudiments, the fundamentals of catching the ball, throwing the ball, running the bases, and with 60,000 people in the stands, you forget it. It just comes. Everything just comes natural. So I just got up and started talking.

“I kind of reflected on where I came from, where I was born and raised. I have a philosophy that the true measure of success might not be how far you went, but from how far you came. So I let them know that. I grew up in the projects, Washington D.C., one of 13 children — eight sisters, four brothers. One bath in the house, one door to the house, the projects — that’s public housing. No future whatsoever.

“One day, a major-league player came to the clinic, (and) by the time he left, I had a direction for the first time. When they signed me, the Dodgers, in 1950 — what’s this, 2014? I’m still here, living my dream. And if you can live your dream, you never have to work a day in your life, and that’s the way it’s been for me. So anyway, that player, he was white — in those days, people didn’t interact as we are today — we didn’t know where he had come from. He was from the Washington Senators, second baseman — actually from Pasadena. (Ed. note: this appears to have been Jerry Priddy.) No one had ever heard of Pasadena. We couldn’t understand where he came from, but by the time he left, for the first time in my life, I had a direction. I knew I didn’t have to grow up and live in these projects and marry one of the girls in the projects and have four babies. I had a direction, listening to somebody like him. I had hope. I had never even dreamed of something like that. So, by the time he left, I knew I wanted to be a major-league player.

“Four years later, the Dodgers signed me, and I started off and I had to learn a lot of things. That’s what I shared with (the campers) — not to be afraid of making any mistakes. The man who’s afraid to make a mistake is the man who’s not doing anything. So you gotta get out there and you go and make a mistake and they correct it, and you make a different mistake and they correct it, and you make another mistake and finally, it starts coming.

“I shared with them the importance of taking care of themselves off the field. That’s super-important. And practice, I tell them with practice, there’s a lot of fallacies. One of them is ‘practice makes perfect.’ No. Practice makes permanent. It’s perfect practice that makes perfect, otherwise you’re compounding the problem.

“That, and I told them, ‘Make your manager like you.’ You can’t do that by bringing him a sandwich every day at the ballpark. You do that by learning how to play the game so when he puts on some strategy like the hit-and-run or the squeeze, you execute for him. I did that for my manager Walter Alston — he was manager of the year several years. He liked me enough to put me on my own on the bases; he never second-guessed me the entire time.

[mlbvideo id=”7150437″ width=”400″ height=”224″ /]

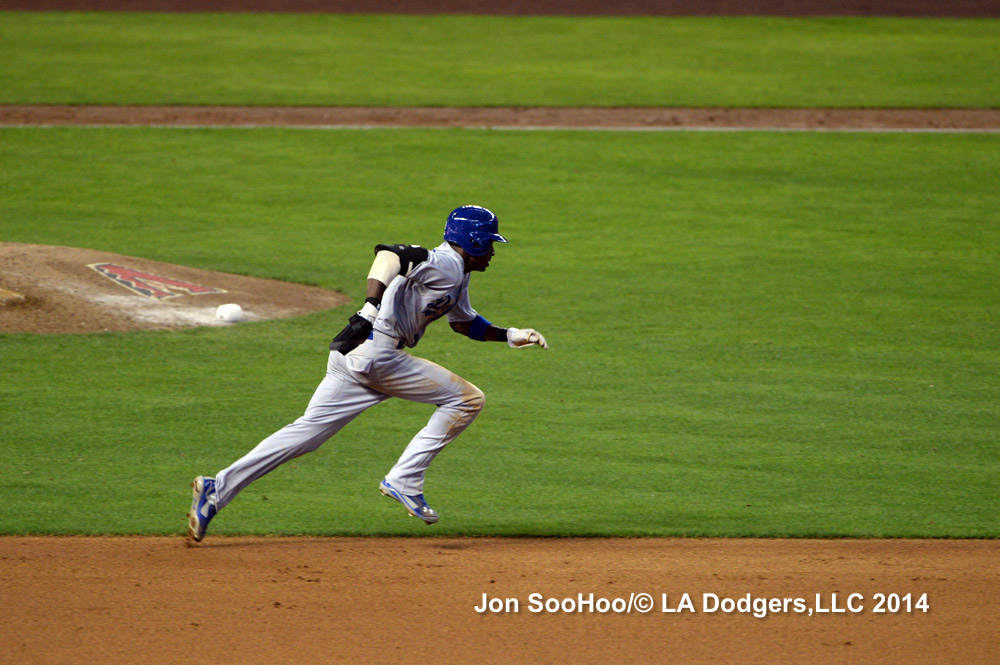

“There were times he took a chance. I didn’t share this with them, but I’m gonna share it with you. I would be on first base in the bottom of the ninth, score tied, nobody out. The play is to bunt me over to second. He asked, ‘Can you get this guy?’ I said, ‘I’ll steal his jockstrap.’ He said, ‘Good — we’ll let you steal it then.’ If I get thrown out then, 60,000 people are gonna boo him. But he trusted me, and I made it. I made sure I got my best jump and my best lead. And I wouldn’t have said ‘I’ll steal his jockstrap’ if I didn’t know that for sure. And that puts me at second, the guy bunts me to third, somebody hits a fly ball, I score and we win the ballgame. Walter Alston there with the press, and he’s having a ball. I looked forward to doing that kind of stuff.

“So, I told them, ‘Listen to your coaches, your manager, and when you get to the minor leagues, always stay ready, because somebody’s going to get hurt.’ We all get the opportunity, but we’re not always ready when it comes. I shared with A.J. Ellis, two years in a row, when he’s gonna get shipped down, long chin. ‘A.J., stay ready — somebody’s gonna get hurt.’ He came up, and then we went back down, and he came up and went down, and the last time he went down, I said, ‘A.J., remember.’ And then he gets the Roy Campanella Award at Dodger Stadium.

“I didn’t share this with them. I meant to. Three years after I got here, a journeyman minor-leaguer, going nowhere, I was named captain of the team. By the players — the players selected me, not just the manager. So I just said what I could say to give them hope, let them know that they can make the big leagues, (that) there’s a position waiting for ’em — but it takes a little work.

“I shared with them the importance of taking care of themselves off the field, get their rest. Lack of rest beats an athlete down more than anything. All distractions are gonna be there for you, but you gotta make sure you get your rest. I got personal enough, I opened up enough to them to be honest enough to tell them, ‘I got 2,034 hits, six times All-Star, but I cheated myself by at least a third because I could have gotten more rest. So I’m a witness to it, that lack of rest. It works against ya.

“I shared with them the importance of taking care of themselves off the field, get their rest. Lack of rest beats an athlete down more than anything. All distractions are gonna be there for you, but you gotta make sure you get your rest. I got personal enough, I opened up enough to them to be honest enough to tell them, ‘I got 2,034 hits, six times All-Star, but I cheated myself by at least a third because I could have gotten more rest. So I’m a witness to it, that lack of rest. It works against ya.

“I know I had their attention, because I kept looking at them. You didn’t hear a chair move. … I mentioned Ty Cobb’s name, and I was wondering if they would know about Ty Cobb, because he was an inspiration for me. Ty Cobb, my last minor-league game I played, I was on a plane to join the Dodgers in Milwaukee. And I had had a good night the night before; I was in Phoenix, playing Triple-A. I got a newspaper and in the article, Ty Cobb was quoted as saying, ‘I like the way that kid slides,’ talking about me. And it just lifted me up.

“Two years later, in 1962 — this was ’59 — in ’62 I broke his record, so I had to read his book. And I sharpened my spikes, too. … He had a reputation of being a rough-and-tough guy, spiking people. I spiked just as many people as Ty Cobb. Because in his book, he said everybody he spiked had it coming, and I identified with that. Because I got bruises all over me. They’d block the base on me, because I’m a little guy, put a knee on me, hit me right in here, tighten it up, and it hurts. So I shared all this kind of stuff with ’em. I had their attention, I think.

“In this stadium right here, 53,000 people would come alive if I was on first base: ‘Go! Go! Go! Go!’ And the word downtown was, ‘I guess Maury’s on first.’

“At my car when I came out, we weren’t fenced in like the players are today. … We parked right out among the fans. Kids be lined up, they used to be all over me. I got an orderly line up, according to height — you never saw so many tall kids get short all of a sudden. And I would stay there to sign them all. This is 2014; in this I’m going back to about 1963, this ringing in my ear right now, I can hear, as plain as day. I had gone to the Reserved Level, trying to hide my car, and when I got out there, they were lined up, because they had gotten wind of it. They were, ‘He’s up here! I got the car!’ So I started signing, there was five little kids, the fifth kid said, ‘You don’t have to shove — he’ll stay until he signs them all.’ I said, ‘Wow.’ And I did. That just hit me right here, to this day.

“I learned that people like you not so much for how good you are at what you do, but for what kind of person. More of us athletes need to know that, because when to be good at what we do, we get full of it. And I can’t say I wasn’t full of it sometimes myself, but I learned along the way. When those kids were lined up, they helped me to learn that what kind of person you are is what really matters.”